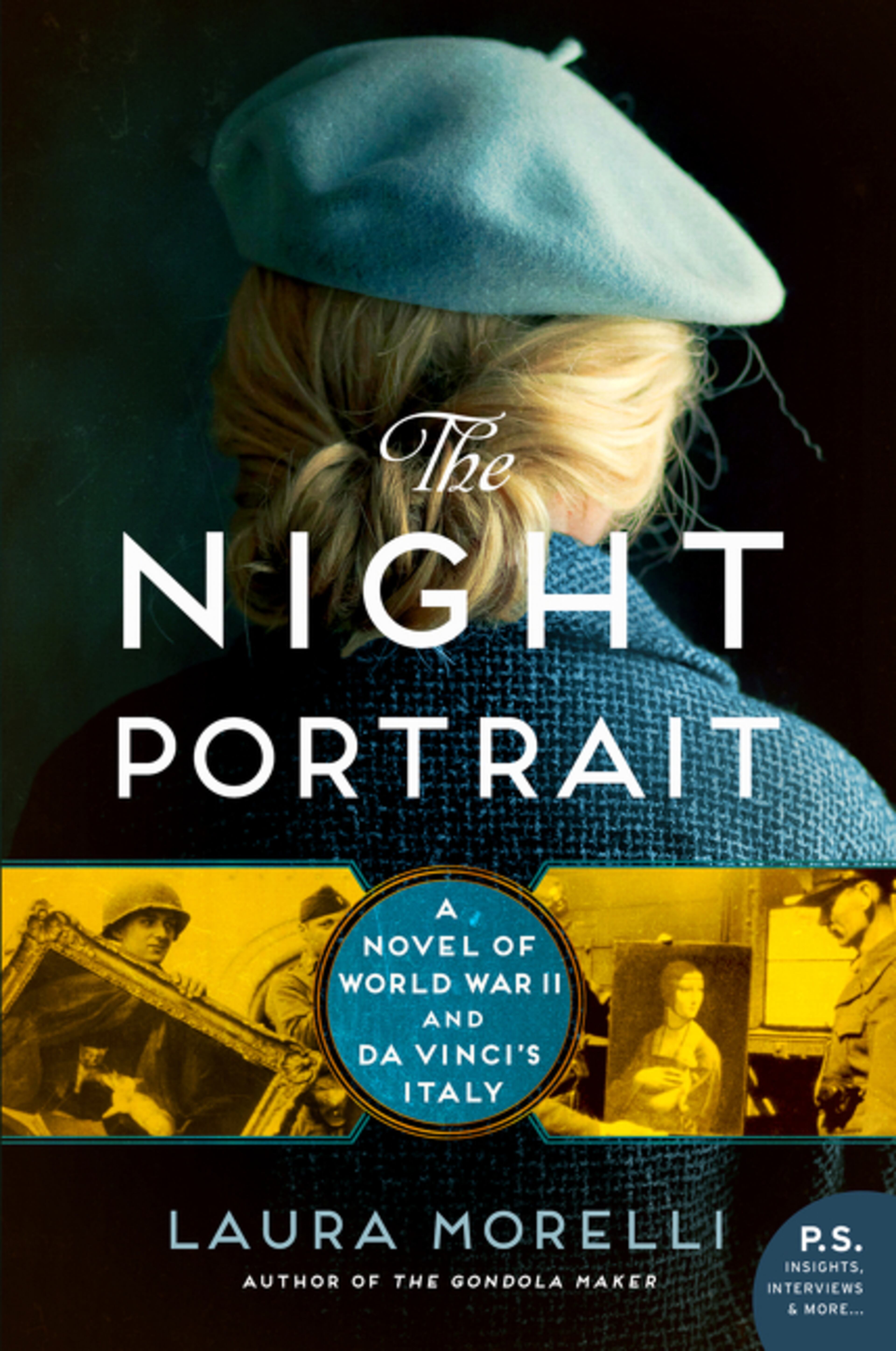

Painting’s heroic backstories span centuries in ‘Night Portrait’

When admiring the beauty of a 15th-century portrait, it’s easy to forget that the artist and the person portrayed were real people, with their own unique challenges in life. Viewers may not consider how much history that piece of art has survived: the various owners, the periods of unfathomable human suffering, the long lines of appreciative viewers, the hungry collectors.

In “The Night Portrait,” Laura Morelli ensures that the focal masterpiece, Leonardo da Vinci’s “Lady with an Ermine,” is seen as more than a beloved inanimate object. The Georgia author positions the painting’s creator and subject as narrators, along with two characters who strive to protect it during World War II.

The historical novel begins with a glimpse into Leonardo’s life in 1476, when he’s planning to leave Florence, Italy, to escape an anonymous accusation of being “a sodomite” — a crime that could send a man to the gallows. He arrives in Milan desiring to design war machines for the city’s de facto duke, Ludovico il Moro.

In 1490, Leonardo is ordered to paint a portrait of Ludovico’s striking new mistress. Before catching Ludovico’s eye, Cecilia Gallerani had been destined for a convent after her brothers blew through her dowry, ruining her arranged marriage before it began. She and Leonardo, both hoping to solidify their standings in society, form a friendship as he paints her elegant likeness.

Five centuries later, the Italian Renaissance painting of Cecilia holding a peculiar white creature comes under the care of a fictional art conservator from Munich. Edith Becker has been ordered to aid in Hitler’s massive effort to steal every important work of art in the world — an especially repulsive notion for someone whose job it is to save art. She and her fiancé, who was assigned to report for Nazi Germany’s armed forces, head “separately to Poland, both pawns in a game that had grown larger than themselves.”

Then there’s Dominic Bonelli, a fictitious Italian-American soldier who wishes the Americans and English had stepped in sooner to stop the mass murder of innocent people, most of whom were being killed “for nothing more than being Jewish.” After proving himself a good cover, he’s put on security detail for a squadron known as the Monuments Men. Their mission is to return confiscated artworks to their rightful owners. An amateur artist who sketches whenever he can, Dominc is initially skeptical of the mission. “How could the American president be worried about paintings and sculptures when thousands of people were losing their lives?”

The author, who holds a Ph.D. in art history from Yale University, creates vivid scenes with striking composition, bringing color and depth to the page. She creates beautiful moments in dark situations: children in lederhosen playing with marbles near enormous swastika flags; a military vehicle’s “headlights pushing golden fingers across dusky tree trunks.” Likewise, she’s able to bring purely horrendous moments to life, searing the results of evil on the psyche.

Fans of “All the Ways We Said Goodbye,” another recent historical novel that tied a World War II timeline to other eras via a cultural touchstone, will appreciate how “Lady with an Ermine” serves as a transportive Portkey. Both books deploy the tactic of connecting characters across time by repeating phrases in adjoining chapters. After having finished Cecilia’s portrait in 1491, Leonardo muses that it’s only a matter of time for a battle in Milan. Dominic has the same thought in 1945 while approaching an art repository in a Siegen copper mine.

All the characters experience similar themes of being at the mercy of other people’s hierarchical decisions. While under the thumb of the Butcher of Poland, who has claimed Leonardo’s portrait as his own, Edith wonders if Cecilia’s serene beauty saved her from falling “prey to the whims of powerful men and events beyond (her) control.” In truth, Cecilia has to remove her body hair with arsenic to appease His Lordship, refrain from speaking unless asked a direct question and worry about having her throat slit because he’s impregnated her.

As Dominic witnesses the death and destruction while tracking down stolen art across Germany, he despairs that it isn’t worth putting one’s life at risk to preserve art while Hitler’s troops are massacring millions and sending them to work camps. But a vicar, who joins the soldiers after they find him hiding in a church, explains that a “world without art, without music, dancing, without the things we do not really need” wouldn’t be a world worth living in. Dominic begins to see the therapeutic effect art has on people who have lost so much.

Edith also endures an internal battle over the work she’s forced to do. While sorting strangers’ personal possessions into three tiers — from the finest masterpieces of Polish collections, to good quality pieces that aren’t worthy of the Reich, to “representational objects” like ceramics and carpets — she realizes she has to take action. Though it means risking her life, she starts to resist. Eventually, her and Dominic’s staggered timelines meet.

Meanwhile, Cecilia works to liberate herself from the confines of being a woman in the 1400s, and Leonardo crafts the masterpiece that will restore his reputation in Florence. By interweaving their struggles and triumphs with those on the periphery of the Monuments Men mission, Morelli has created an absorbingly layered tale on why people fought so hard to safeguard these masterpieces, which are irreplaceable sources of joy for so many.

FICTION

By Laura Morelli

William Morrow

455 pages, $16.99