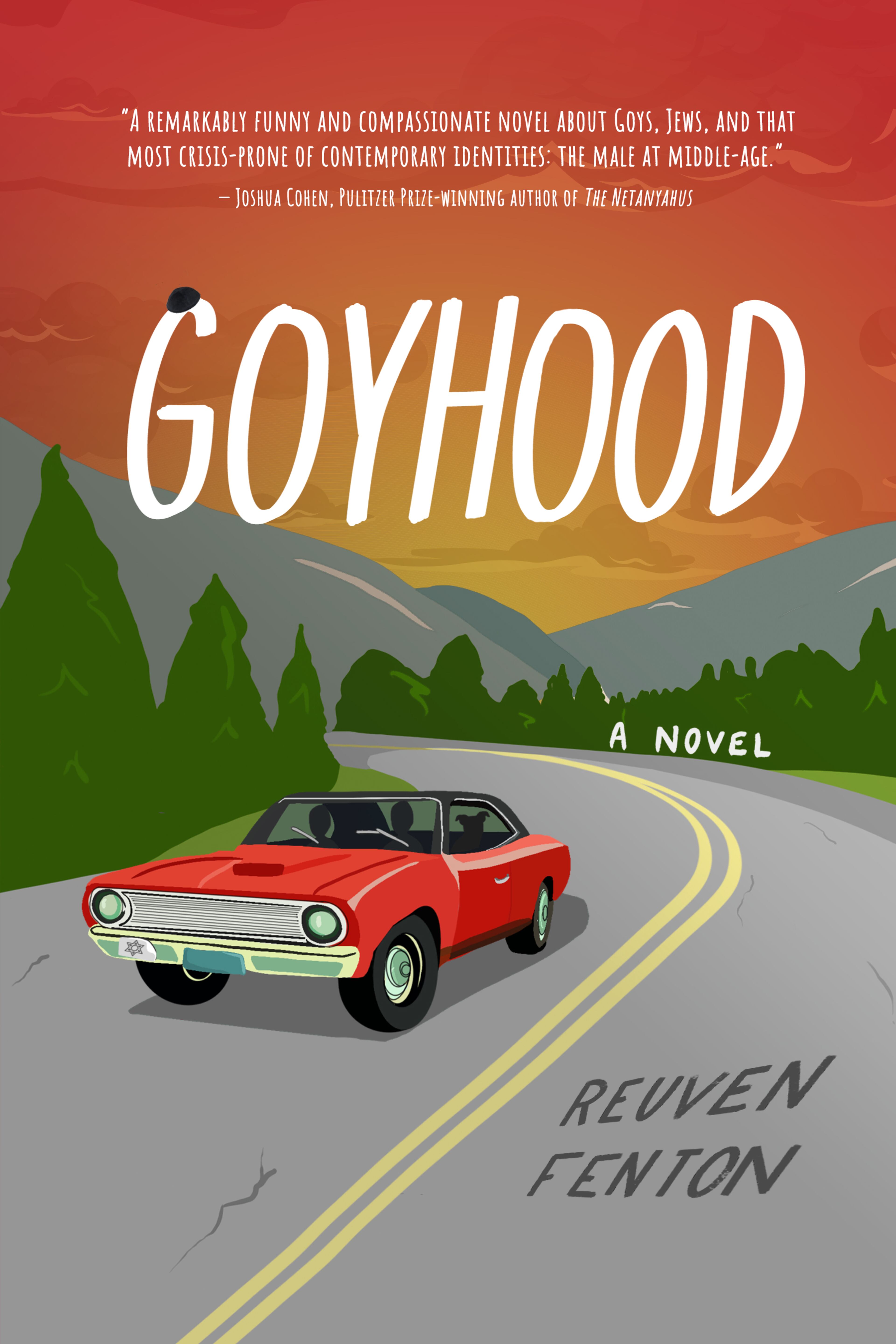

Middle-aged brothers explore Jewish heritage on a road trip South in ‘Goyhood’

From the outset, the Old Testament roils with brotherly conflict. There are Cain and Abel, Jacob and Esau.

Well, meet their 1990s iteration: Martin and David Belkin. Although they are twins, and sons of a shambolic, irresponsible mother named Ida Mae in small-town Georgia, they could not be more different.

In this debut novel by a New York Post reporter, Reuven Fenton’s writing is at its strongest when the boys are together, romping in their early, grubby, knockabout adventures. He has a knack for the telling, visually arresting detail: “Their Schwinns, bought for 10 dollars apiece at the Salvation Army, were propped against the side of the house. Marty’s crankset was stuck permanently in high gear, and David’s tires had as much tread as a pair of bluejeans, but the bikes got them where they had to go. Tied to the back of Martin’s seat was a dream catcher he’d made out of woven willow sticks, dental floss and wild turkey feathers.” Most of us have had chariots like that.

His character sketches, too, are to be relished. The boys’ negligent mother: “She hugged like a bear and kissed like a lamprey, called Marty ‘Monkey’ and David ‘Doodle’ and saved every art project they brought home from school. She also had a weakness for gin, amphetamines and men who smelled like motor oil.” Not an auspicious beginning for these boys who find different ways to fend for themselves while so often left to their own devices.

On the cusp of adolescence, they are startled to learn of their Jewish roots. More could be made of the relative exoticism of Judaism in the rural South, but Fenton lets the street names – Bragg, Lee — subtly speak for themselves. Martin changes his name to Mayer and nose-dives into the Torah while David, a mischief-driven hipster, takes the secular route, always looking for the next get-rich-quick scheme, the next good time.

They soon enough part ways, with Mayer fleeing for Brooklyn, where he becomes a Talmud scholar and marries into one of the greatest rabbinical families in the world. A late-to-the-bar-mitzvah bumpkin, he makes up for his lack of early training with enthusiasm, becoming the hoary-bearded, hyper-serious image of the patriarchal God he holds dear. He holds center stage for a while, toiling over the arcana of the Gemara.

If you were wondering about the atonement ritual for leprosy (a hyssop plant is involved), this book is for you. The Hebrew phrases come fast and furious, but always with translations. You do not have to be Jewish to enjoy this novel, but it likely would enhance your reading experience. Fenton clearly knows his Talmud. “Der mensch tracht, un gott lacht” — “Man plans and God laughs.”

David, meanwhile, coasts from gig to gig and woman to woman. He speaks in a “mashup accent of Popcorn Sutton and Venice Beach stoner.” (Another winking allusion to the South.)

Their mother’s untimely death unites them, now middle-aged, and brings a revelation. Not only are they not Jewish; but a Nazi also haunts their lineage. Talmud scholar Mayer is, gulp, a goy, invalidating his marriage into Jewish royalty. Because of rabbinical scheduling, he has a week before he can convert and possibly woo back his imperious wife, Sarah. David, with a gleam in his eye, decides it is the perfect time for a “Rumspringa” through the Deep South.

At this point, the book picks up steam as a picaresque, à la Kerouac’s “On the Road” with a dash of the book of Exodus thrown in for spiritual gravitas. There is much exploration in the wilderness, from the topless revelations of New Orleans to the Great Smokies. Along the way, they pick up a one-eyed dog and an Instagram influencer.

The story would not be complete, of course, without a run-in with a white supremacist named Cletus, and Mayer loses an eye, all the better to see with a clarified vision. Will the scholar convert and resume his old life amid the midrash? Will Sarah take him back? What awaits these would-be fusgeyers, or Wandering Jews? These questions loom until the end.

In most sibling dynamics, the oldest is the more responsible one, but the Belkin boys are hardly ordinary. David, who calls his brother “Ese,” is the elder and the agent of chaos, the one not bound by millennium-old rules and a structured, regimented place in society. He has some growing up to do, to be sure, but it is Mayer who changes the most over the course of the story. He ultimately proves a charming man, with or without tefillin. It is somehow heartening to see him pick up a pair of binoculars and resume a childhood habit of bird-watching – God’s presumptive handiwork in flickering motion, not just rules laid out in a book. Another metaphor for his ever-sharpening vision.

With the stakes of Jewish identity so high right now, “Goyhood” makes a powerful case for the undeniable endurance and jaunty appeal of the religion.

FICTION

‘Goyhood: A Novel’

by Reuven Fenton

Central Avenue, 288 pages, $28