A true-crime idyll of cotton, corn and corpses, Earl Swift’s “Hell Put to Shame: The 1921 Murder Farm Massacre and the Horror of America’s Second Slavery” examines the 1921 murders of 11 Black “peons” near Monticello, south of Atlanta.

At the time, the prosecution of John S. Williams, a planter and prominent “churchgoing Christian” accused of the killings, drew intense media scrutiny, not unlike the sensational Alex Murdaugh trial in South Carolina’s Lowcountry a century later.

Yet, the scale of the coldblooded liquidations perpetrated by Williams, aka “Mr. Johnny,” and his equally sadistic sons dwarfs anything Murdaugh might have cooked up. Their three plantations, spread over Newton, Jasper and Butts counties, would become known as the “Murder Farm.”

“The Williams worked two classes of Black farmhands,” writes Swift. The more fortunate “were paid wages or earned shares of the income from the crops they raised.” This group includes the family’s African American “farm boss,” Clyde Manning, an unwilling accomplice who is forced by his master to kill.

The others, so-called “stockade negroes,” are bonded out of jails in Macon and Atlanta where they’re held on trumped up charges like vagrancy. When farmers like Mr. Johnny materialize with bail money — which, as his captives, they can never afford to repay — the prisoners find themselves trapped in a sinister scheme designed to secure free labor at the Williams estates.

Controlled by dogs that are trained to track runaways, these men are essentially reimprisoned, forced to work the crops and subjected to daily rounds of beatings and torture.

This condition of debt slavery is known as “peonage,” a word the author first stumbles upon when he comes across the Murder Farm story while researching an earlier book. Peonage “reduces its victims to the status of livestock,” Swift writes, adding, “And most of these victims have dark skin.”

In early 1921, escapees from the Williams’ plantations appear at the Atlanta branch of the Bureau of Investigation (later known as the FBI) and inform agents about the murders of farmworkers committed by Williams and Manning.

On one of the Williams’ properties, investigators discover troubling evidence of peonage: a strange red bunkhouse that’s really a cell with a padlock and chain system. Oddly, a machine for resoling shoes using old tire tread is present, as well, and “Hell Put to Shame” takes shape as a haunted, historical legal thriller.

Soon, bodies of peons begin popping up in the area’s three jagged rivers. Bound with wire and “trace chain,” weighted down with rocks or even an iron wheel, the victims have been clearly dropped from various bridges.

Of course, the tire tread soles of their footwear are the giveaway. Manning turns state’s evidence and becomes a powerful witness against Williams. He directs sheriffs to the pasture graves of other peons killed by ax blows and shotgun blasts. The serial slaughters are a succession of kill-crazy cover-ups to conceal the initial slayings, though Williams and Manning will be charged with a single murder and tried separately

The events of “Hell Put to Shame” take place at the conjuncture of the Great Migration and the era’s antisemitic hysteria, ongoing in the aftermath of the infamous Leo Frank lynching of 1915. In Swift’s account, attorney Hugh Dorsey led a bigoted prosecution that “inflamed” the mob that later hung Frank in Marietta. “The trial made the lawyer both a hero to thousands of Georgians and an international pariah.” Dorsey was elected governor in 1917.

And yet, in an inconceivable about-face, Dorsey experiences a “Turn to enlightenment” — there’s speculation he was deeply shocked by the horrific South Georgia lynching and burning of a young Black woman, Mary Turner. Whatever the reason for his transformation, Dorsey emerges as a courageous figure in the Murder Farm story, organizing the prosecutions and bringing in a highly skilled barrister, William Howard.

The Covington courthouse is the setting of a classic Jim Crow spectacle: white citizens fanning themselves on the floor, Black spectators sweltering in the balcony, and prosecutor Howard delivering a splendid oration damning the ghoulish John Williams, before collapsing from heat exhaustion.

William’s flamboyant defense lawyer, Greene Johnson, plays every card in the race deck to influence the all-white jury that Manning is the sole responsible killer:

In his testimony, Manning remains steadfast and convincing: “Whatever [Williams] told me to do … if it was against my will, I would go on and do it … I was there long enough to find out you had to go on and do it.”

A Virginia resident, Earl Swift, who previously tracked down all 13 owners of a single 1957 Chevrolet for his 2014 book “Auto Biography,” roams the landscape, searching for the pauper’s cemetery where many of Williams’ victims were buried; it’s a personal quest to provide men like Little Bit, Blackstrap and Iron Jaw a measure of dignity they never received during their lives.

When the arcs of American history and race coincide in extreme violence, happenings of great magnitude mysteriously become obscure; knowledge of events like the Murder Farm, Mary Turner’s lynching or the gargantuan Tulsa riot is submerged or buried with the victims, at least for a while.

Swift notes that peonage is still with us today, “[having] morphed into a complex international undertaking, shaded into human trafficking, fraud and money laundering.”

Thus, “Hell Put to Shame” presents a quantum entanglement of evil, and, for its author, there is a lesson to be learned: “That he past lurks close. That we haven’t learned as much as we think we have. That maybe we never do.”

NONFICTION

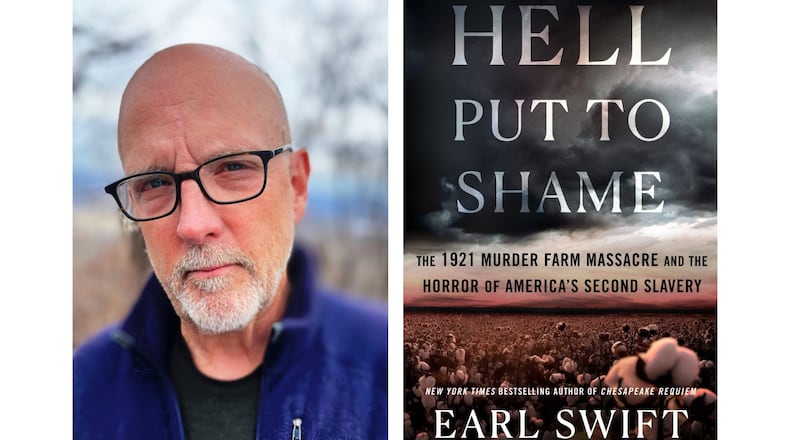

“Hell Put to Shame”

by Earl Swift

Mariner/Harper Collins, 432 pages, $32.50

About the Author

Keep Reading

The Latest

Featured