An oil rigger, a math teacher and a world-class art collection for Emory

Half a century ago a Georgia boy named Wes Cochran wrote a letter to his uncle that would change his life.

Cochran was born and raised in LaGrange, and like the rest of his family, lives there to this day. “But my uncle William May was different,” says Cochran. “He fled as soon as he could and became an international art broker, living 9,000 feet up on the edge of a cliff in Colorado.”

Cochran had just graduated from the University of West Georgia in Carrollton in 1974 and wrote his uncle telling him, “I didn’t know what to do with my life. I only knew that, wherever the herd is going, I’m going somewhere else. … He replied with a 14-page, single-spaced, typed letter and invited me out to live with him and his wife for a while.”

That winter in Colorado cast a kind of spell over Cochran. From his uncle’s living room in the sky, he could see the Continental Divide and the skyline of Denver. May was a spellbinding storyteller (Spend an afternoon with Cochran, and you’ll find he inherited the same silver tongue) and a prodigious art collector. His print collection spanned 500 years and 1,200 pieces, from Rembrandt to Picasso.

“I might have been a lost soul without my uncle’s influence,” muses Cochran, who found himself lit by the same fire for collecting art and eager to dedicate his life to the task. His uncle convinced him art was a good investment and a hedge against inflation.

In one of the many letters he wrote Cochran over the years he explained: “The gratification of being up close to the action of a planet of artists is a rare circumstance in human affairs. It is a loner’s trip. Few around you can comprehend the enormity of your undertaking. Drink constantly from its fathomless fountain of joys and bask in its meadows of self-fulfillment.”

Today Cochran, along with his wife Missy, is a widely respected 20th century print collector and gallery owner. Their collection includes Warhol silk-screens spanning nearly 20 years and numerous prints by titans such as Jasper Johns, Jean Miro, Will Barnett, Alexander Calder, Jim Dine and Roy Lichtenstein.

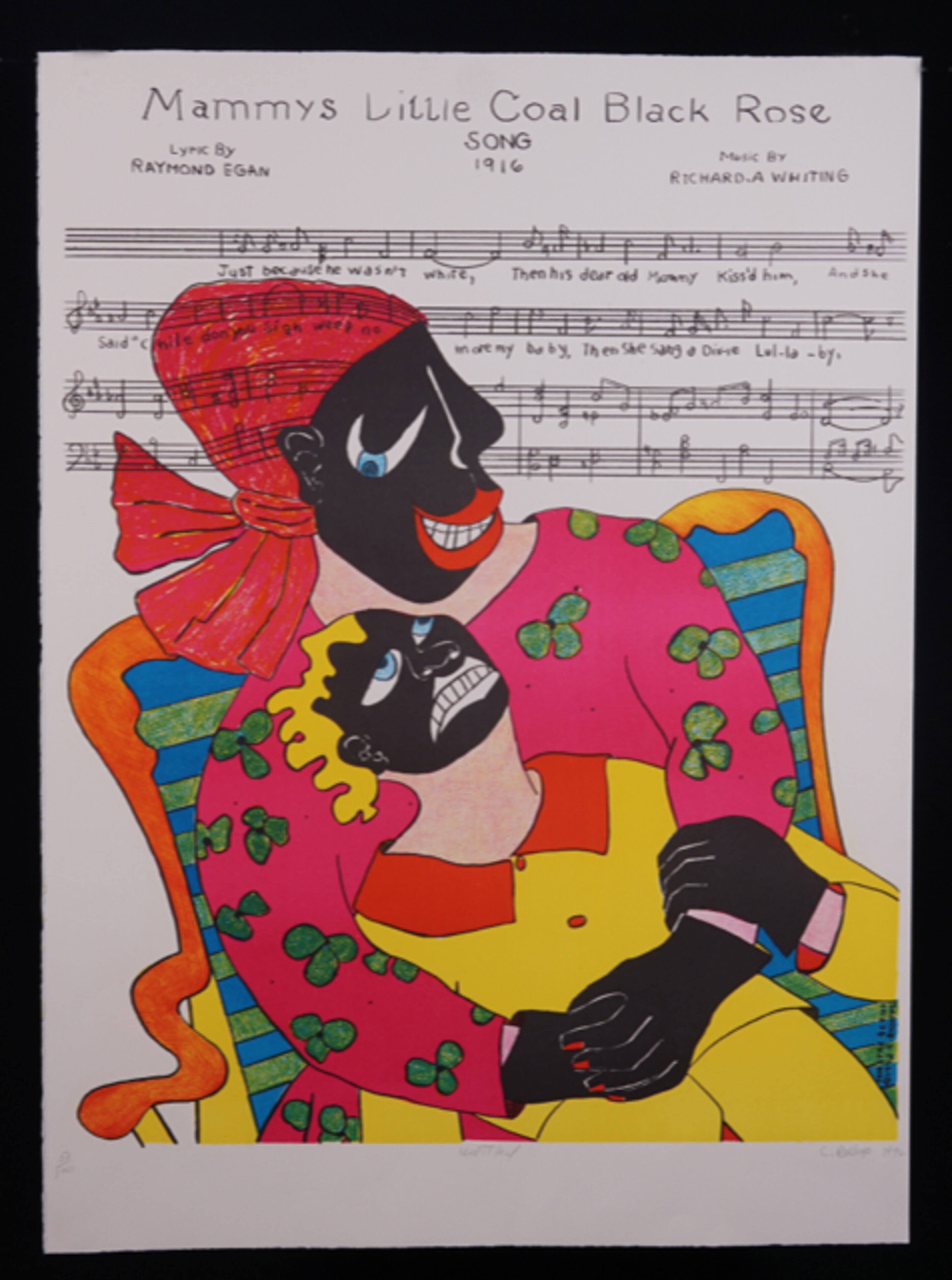

But perhaps most notable of all is their collection of more than 500 original engravings, drawings, silk-screens and lithographs by African-American artists, which was recently purchased by Emory University’s Michael C. Carlos Museum. A selection of pieces was displayed this summer in the John Howett Works on Paper Gallery.

“It’s a formidable collection, impossible to duplicate,” says the museum’s print curator, Andi McKenzie. “It is the best collection of works on paper by African American artists that has ever existed in private hands. And Wes and Missy are such incredible people. They’re just happy to share the works.”

There is a fairy tale quality to Cochran’s life story, at least the way he tells it — where larger-than-life figures show up bestowing wisdom and requiring only dedication and hard work in return.

“You have to be sure of yourself and never waver,” he says, musing on what it took to step up to his fate.

The couple met in 1981 and married four years later. Cochran worked as a stonemason and Missy as a high school math teacher. In their 60s now and both retired, there is an easy comfort to their bond.

Wes is tall and broad shouldered, usually wearing a colorful shirt, maybe some beads and a hat, be it a fedora, boater or gambler style. A cigar perpetually cantilevers from his mouth, upon which he may chew but never smokes. Missy, smaller and neatly dressed, provides a quietly charming foil to Cochran’s looming presence.

On any given day you are likely to find him seated at a large gleaming desk at the front of Cochran Gallery, on the main square in LaGrange, across from a large park and fountain.

The 2,300-square-foot gallery opened in 2007 and features rotating exhibits that change about every two months. Currently on view is figurative works by painter Tom Barnes. “Slow Exposures” photography show opens Sept. 27.

“I’ve known the Cochrans for 20 years,” says writer Pam Avery, “and what’s unusual about them is their unpretentious and inclusive approach. No matter who walks into that gallery, Wes will make them feel at home. That itself is an art right there.”

Pieces from the Cochrans’ collection have been exhibited in more than 200 museums. Wes builds the wooden shipping crates himself. “In the early days I was the truck driver and delivery boy,” he says, but of late the museums handle the transportation.

Their collection was shaped in large part by two very different, flamboyant mentors.

The first was May, Cochran’s uncle, who told him to “break all your pencils and buy a gross of workman’s gloves, go overseas to the oil rigs, and use your money to invest in art.” Not long after, Cochran landed an offshore drilling gig in the Persian Gulf. The work was grueling and dangerous, but the pay great, and he started sending his uncle money to buy art. His first purchase was a Salvador Dali for $1,200. By the time Cochran got back to LaGrange two years later, he had a starter collection of 10 prints including pieces by Alexander Calder, Karel Appel and Romare Bearden.

“The surprise of my life was when I finally came home and looked for the first time at my acquisitions,” he recalls. “They shocked me, but I was drawn to them. They were very contemporary, often abstract. It was all new to me at that time.”

For 10 years, May chose every print the Cochrans bought. “I did nothing but work and save to add to the collection. Every extra dime went toward art,” he recalls. Then, in 1987, his uncle died after a battle with cancer. He left no rolodex of contacts behind.

“He always said I would be a lamb among wolves in New York in the mainstream gallery system. We were a bit lost. Missy and I had to stand on our own two feet.”

But within six months, the Cochrans were sitting in the 4,000-square-foot New York City loft of Camille Billops, a charismatic Black artist, archivist, filmmaker and librarian, who would be their second mentor.

Cochran recalls the day he cold-called her. “She asked me if I were Black or white. I said, ‘I’m white.’ And she said, ‘Well, come on and visit anyway.’ She was as flamboyant and charismatic as my uncle; always draped in coral jewelry with dramatic Egyptian-style makeup and a huge, 10-gallon black hat. We spent four or five hours that first visit, and she loaded us up with an armful of books. She told us to read and learn about the field before buying any art.”

To this day he regards meeting her as another act of fate. “Sometimes I felt like my uncle had been reincarnated into this woman.” A 30-year friendship blossomed, and the Cochrans regard her as the true curator of their African American collection.

Today, the Cochrans divide their time between the modest brick home in LaGrange where Missy grew up and the stone house Wes designed and built in the woods half an hour away, where they also keep horses.

One of their greatest joys is sharing their collection with an appreciative audience. When a visitor asked to see a Jasper Johns up close, a lithograph titled “Viola” was presented, one of only 70 in existence.

Inspired by the American choreographer and dancer Viola Farber, the print features painterly floating squares of gray and white; the dancer’s name, both bold and faint, layered on top of one another; a mysterious spoon and fork, upright like guards at attention, tethered to one another in the margin. (According to Wes, the dining utensils reference the way choreographer Merce Cunningham tethered himself to his dancers with a big elastic band.) The harmonics of the print are serene, sultry, unforgettable. Its ability to inspire, transport and evoke illustrates the magic of art. Through fate, fortune and hard work, Cochran and his wife have lived by and for that magic, and now they are bringing it to others.

ART EVENT

The Cochran Gallery. “Tom Barnes Art” on view through Sept. 7. “Slow Exposures” opens Sept. 27. 4 E. Lafayette Square, LaGrange. wes@cochrangallery.com, www.facebook.com/TheCochranGallery