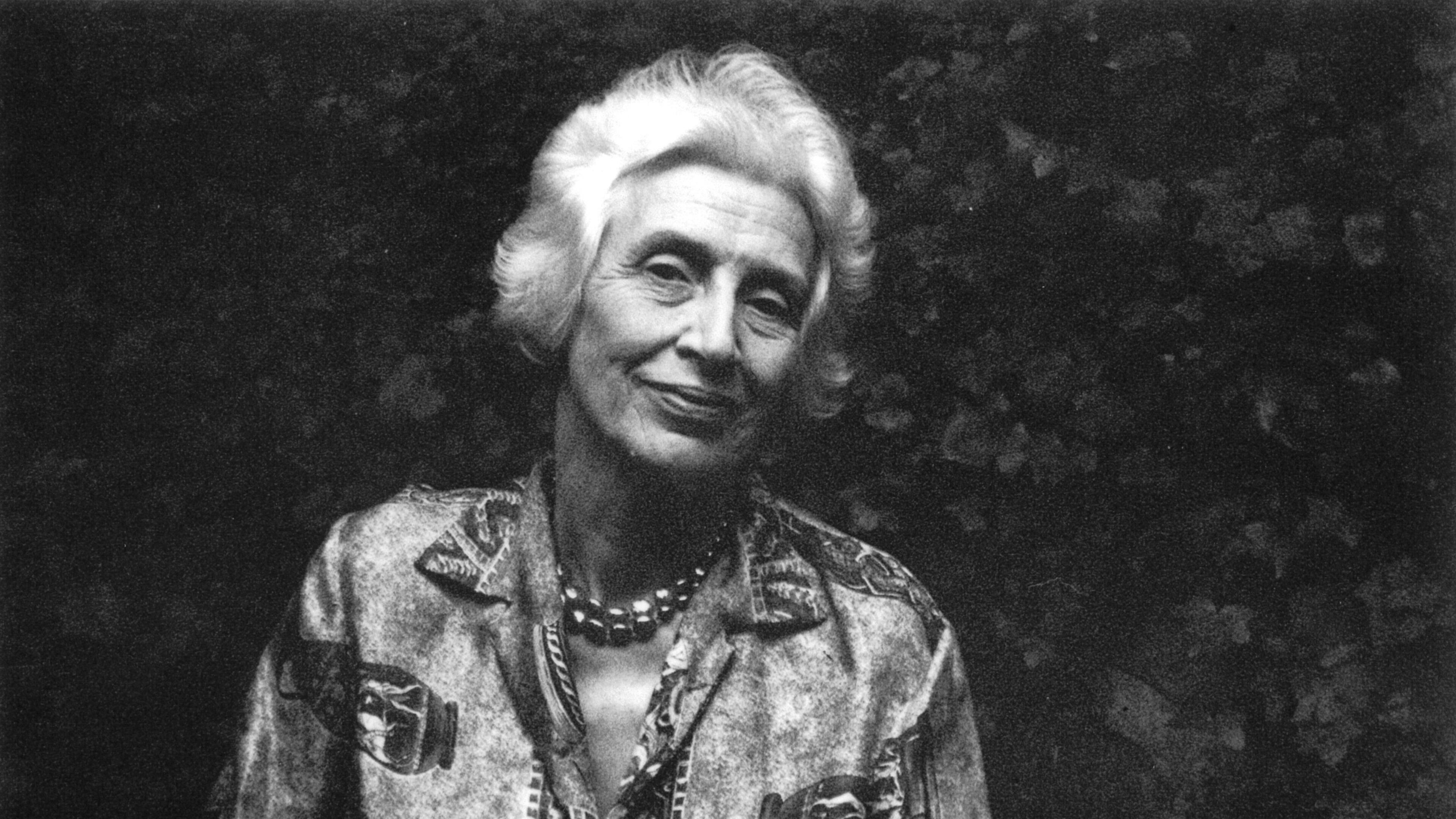

Georgia author Lillian Smith broke taboos, fought segregation

SCREAMER MOUNTAIN, CLAYTON, Ga. — Lillian Smith was a Georgia writer, fearless activist, philosopher and teacher who has been gone for almost 50 years, but her spirit still hovers over the tranquil mountaintop retreat here that was her home, her headquarters and ground zero in her campaign to change the world.

Her papers and books are still scattered over the desk in the rustic cabin where she spent her last days. An autographed book from the Rev. Martin Luther King Jr. sits on the coverlet. (“To my dear friend, Lillian Smith,” he writes.)

A cassette recorder rests with one button depressed, as if time has pushed the pause key in this isolated North Georgia world.

Such was not the case when Lillian Smith was alive and engaged with the most violent issue of the day. Her writing struck at the heart of the vile system of segregation, and consequently she was threatened and ridiculed by those on the right and celebrated by those on the left. Smith was surveilled by the FBI, harassed by the U.S. Postal Service, received death threats, embraced by Black literary leaders from Alice Walker to James Baldwin and rescued by Eleanor Roosevelt when her novel “Strange Fruit” was banned in Boston.

“Strange Fruit” (Harper Paperbacks, $21.95), a story of an interracial romance, was published in 1944 and became an instant sensation, selling up to 30,000 copies a week.

The 1939 song of the same name, voiced by Billie Holiday, was an overt cry against racism and lynching: “Black bodies swingin’ in the Southern breeze / Strange fruit hangin’ from the poplar trees.”

Smith’s novel was subtler, a portrait of a culture that stunts the emotional growth of both white and Black. She has commented: “It is a book not about a lynching, but about children in anguish, white and Negro children, forbidden to grow openly as human beings. They are the strange fruit on white culture’s twisted branches.”

Written out of history

Five years later she published “Killers of the Dream” (W.W. Norton, $16.95). Part memoir, part jeremiad, it was an unequivocal broadside against white supremacy that was both political and intensely personal. In the introduction to the 1961 edition she explained, “I wrote it because I had to find out what life in a segregated culture had done to me; one person.”

Southern bookstores wouldn’t carry it and Southern newspapers wouldn’t review it. Matthew Teutsch, director of the Lillian E. Smith Center at Piedmont University, said this blackout was purposeful and unlike being banned in Boston, it couldn’t be fought in the courts.

The result: Many students of the South grow up unaware of Lillian Smith. “I thought I knew about Southern literature,” said Keri Leigh Merritt, an Atlanta-based historian whose biography of Smith will be published by St. Martin’s next year. “I never heard Lillian Smith’s name until grad school.”

Merritt participated in a recent symposium on Smith in Decatur sponsored by the Smith Center and the Georgia Center for the Book. Also appearing was Jennifer Morrison, assistant professor of English at Xavier University in New Orleans, who said she didn’t encounter “Killers of the Dream” until her doctoral work.

“I was blown away,” she said. “She was writing about race as honestly as I’ve ever seen it from a white perspective. It surprised me. I didn’t realize how much I wanted to see that.”

This symposium is part of an effort by Teutsch and Piedmont University to lift up Smith’s profile on the 75th anniversary of the publication of “Killers of the Dream,” and to acknowledge her role as one of the earliest white voices speaking out against segregation.

Others have exerted similar efforts.

In 2010 Smith’s niece, Nancy Smith Fichter, sought a way to include Smith’s mountain home as part of the Southern Literary Trail and contacted Atlanta actor Brenda Bynum about a public reading of Smith’s letters.

Bynum became fascinated with the writer/activist and created a one-woman Lillian Smith show, “Jordan is so Chilly,” that toured the Southeast for the next 10 years. “I fell down the rabbit hole, I’m telling you,” said Bynum.

Bynum also appears in a 2019 documentary by Atlanta filmmaker Hal Jacobs, “Lillian Smith: Breaking the Silence,” which can be streamed at hjacobscreative.com.

“Lillian was warning us about demagogues,” said Jacobs. “Her message was so perfect when the film came out in 2019, talking about how toxic white supremacists were and demagogues that preach it. She’s so relevant now.”

Smith’s family eventually donated 150 acres including her cabin and several others to Piedmont University, which turned it into the Lillian E. Smith Center. Piedmont students visit the center as they learn about this unusual woman.

Origins of conscience

Lillian Eugenia Smith was born in Jasper, Florida, the seventh of nine children. Their father was a successful entrepreneur who employed hundreds of poor white and Black laborers in his turpentine mills.

The father’s businesses collapsed in 1915, and the family moved to the mountains of North Georgia, where the parents owned property that they turned into a summer camp for girls.

Lillian Smith pursued studies at Piedmont College and worked toward a career as a concert pianist, but when her parents’ health failed, she reluctantly returned to take over running the camp, called Laurel Falls.

At the camp she met a counselor named Paula Snelling who became her lifelong partner, and who encouraged her earliest writing efforts.

Though the camp was not integrated, Smith hosted interracial get-togethers for white and Black women, drawing the likes of Mary McLeod Bethune, Eslanda Robeson (Paul Robeson’s wife) and Sadie Mays, the wife of Morehouse president Benjamin Mays.

She also inspired serious discussions among her young campers about current events, Southern “traditions” and the role of women in the South.

It is one of the puzzling mysteries of Southern life that the elite Atlantans who favored segregation also sent their daughters to Laurel Falls. “The camp was an eye-opening experience Lillian Smith used to get these young Southern women to think about more than just getting married and having children,” said Smith scholar Rose Gladney.

A mountain home

Smith cherished the isolation of the North Georgia mountains but also traveled widely, made friends around the world and interacted with the issues of the day through her literary magazine, South Today, that eventually had 10,000 readers.

Operated by Smith and Snelling, the quarterly magazine printed poetry, essays, book reviews (they panned William Faulkner) and featured the writings of Pauli Murray and W.E.B. Dubois, among others.

Merritt said Smith only came to Atlanta to receive treatments for the cancer that eventually killed her in 1966. She was being given a ride to Emory University Hospital by Martin and Coretta King for one such treatment when police stopped them and issued King a citation for an expired tag.

(That ticket led, in a roundabout way, to King’s imprisonment in Reidsville, a few months later, and presidential candidate John F. Kennedy’s intercession on his behalf.)

The isolation of Rabun County didn’t protect Smith completely from the threats and hatefulness extended her way by segregationists, and one of the cottages of the camp was burned one night under mysterious circumstances, taking with it some of her books and a few irreplaceable manuscripts.

Teutsch offered a tour of the grounds on a recent sunny morning, pointing out the ruined foundation of the burned cottage among the other structures. Dwarf irises were blooming around the plaque that marks Smith’s grave site, a few steps removed from the camp.

On the porch of one of the stone cottages, Jaye Johnson Thiel watched the sun creep over the nearby hills. A professor at the University of Alabama, she was just starting a two-week residency at the center to work on a few articles and a book about communication and children. There are between 30 and 50 residencies a year at the center, sponsored by donations. “This is like stepping back in time,” said Thiel, “like being with my grandmother again.”

Teutsch would like to see more events at the center, which is about an hour from Piedmont’s campus, but the mountain retreat is currently accessible only by a steep one-lane dirt road that needs grading.

In 1951 Smith predicted that segregation would be over in 10 years. No one else believed her.

“I’m fascinated with women who know something before anybody else does and do something about it,” said Bynum, of the woman she portrayed on stage. “They don’t have to be told if it’s right or wrong. They know it in their bones and are compelled to live their lives in service to that knowledge.”

More information

Visitors can see the campus of stone cottages at the Lillian E. Smith Center at Piedmont University by appointment only. To schedule, email lescenter@piedmont.edu.