True crime fans have two terrific new page-turners to read this fall, both of them based in the Lowcountry and written by journalists.

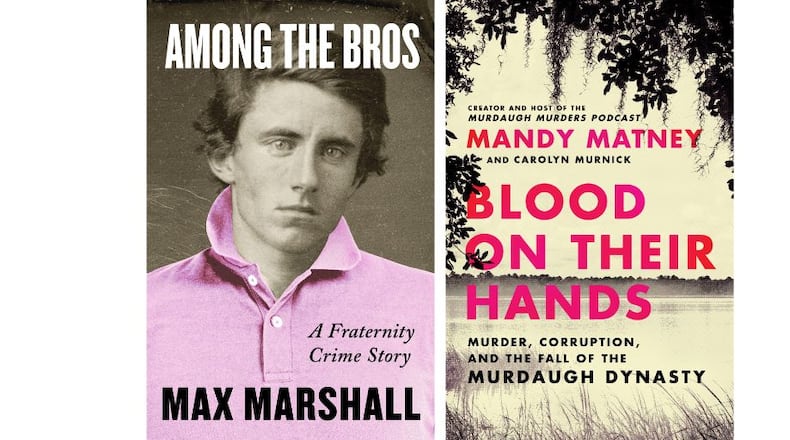

“Among the Bros” (HarperCollins, $30) by Max Marshall is an incredible tale of generational wealth, privilege and excess that ends with death and imprisonment for some and a slap on the wrist for others. It’s a story about a group of “golf shirt-wearing, swoopy-haired” fraternity brothers at the College of Charleston who got busted in 2016 for operating a sizeable interstate drug ring that sold primarily to college students,

Much of Marshall’s story focuses on Mikey Schmidt of Dunwoody, who got the longest sentence in the case. He gave the author full access from his prison cell at Wateree River Correctional Institute in South Carolina, where he is serving 10 years without parole.

A rambunctious kid who sold a little weed in high school, he arrived at the College of Charleston as a freshman in 2014. The first friend he made was Rob Liljeberg, who recruited him to join Kappa Alpha fraternity. The two instantly bonded over their shared affinity for marijuana and Greek life, although they couldn’t have been more different.

Liljeberg was an Eagle Scout, a National Honors scholar and would become president of their Kappa Alpha chapter. Schmidt eventually got kicked out of school for bad grades but remained an honorary member of Kappa Alpha as he divided his time between Charleston and Atlanta, where his VIP valet gig at Tongue & Groove nightclub and illicit drug sales initiated him into Atlanta’s rap scene.

The first part of the book delves deep into the secret world of fraternities — the rivalry between orders, the rushing, the hazing, hell week. Where Marshall really breaks ground, though, is his exposure of the volume of drug and alcohol abuse that fueled the fraternities’ social gatherings.

I have no idea what constitutes “partying” among college students today, but, according to Marshall’s account, during this time at the College of Charleston (and at a lot of other schools, too, apparently) it sounds deranged. Drawn from multiple first-person accounts, his description of Sigma Alpha Epsilon’s 2012 Mountain Weekend party at Tugaloo State Park in Georgia is so unhinged, it ends with a Hummer in the lake and every stick of furniture from eight cabins burned in a fire.

A contributing factor to the debauchery on campus was the sudden availability of Xanax. Students started taking it as a way to mitigate their hangovers. Then they took it to enhance a night of drinking. Some fraternity members drank punch spiked with the drug in order to purposely black out. “It’s cool to not remember,” a Kappa Alpha from Duke University tells Marshall. “It’s cool to be like, ‘Bro, what happened?’”

This is the atmosphere in which Schmidt and Liljeberg begin to ramp up their weed and Xanax sales. Then entered Zackery Kligman, son of the owner of Klig’s Kites, a long-standing gag gift shop and kite store in Myrtle Beach, South Carolina. Kligman started out dealing Xanax, then, according to Marshall, began mass producing counterfeit versions of the drug. Kligman also liked cocaine.

Together the three men formed an interstate drug triangle in which Schmidt and Kligman never met and Rob was the middle man. As Marshall explains it, Schmidt secured cocaine by the pound from a cartel member in Atlanta and sold it to Liljeberg in Charleston, who sold it to Kligman. Meanwhile, Kligman sold large quantities of counterfeit Xanax to Liljeberg, who in turn sold it to Schmidt. Much of the interstate transportation of the drugs was carried out by fraternity pledges.

For a while they all lived like kings until Patrick Moffly, the aimless, out-of-control son of a wealthy builder of “homes for billionaires,” was murdered in a drug deal or theft, depending on who you ask, or possibly a hired revenge killing. Regardless, it was the instigating factor that led to the arrest of nine people, only three of whom did actual time.

Without commentary and by simply stating the facts, Marshall draws attention to how some people were held accountable for their crimes and others appeared to get a pass.

For instance, Moffly’s dying words identified his friend Jordan Piacente as one of his killers, and she gave police conflicting information about her alibis, yet she was never pursued as a suspect. And Kligman’s history of arrests and dropped charges is downright jaw-dropping.

There is so much more going on here that I haven’t even touched on like the death memorial parties and how deep fraternity culture runs among our country’s power brokers. It’s chilling stuff. But at its core, “Among the Bros” is a deeply researched, well-crafted and disturbing story about elite young adults spinning out of control.

Speaking of wealth, privilege, death and destruction, the 2021 murders of Paul and Maggie Murdaugh by their patriarch, Alex Murdaugh, has been so widely reported it’s hard to imagine there’s a person in the country who isn’t familiar with the details. It’s been covered by every news outlet under the sun and spawned seemingly dozens of televised documentaries. But for those like me who started following this story before the murders, when it was about Paul drunkenly smashing a boat full of teenagers into a bridge piling and killing Mallory Beach, there was one definitive source for the most updated information — journalist Mandy Matney.

Writing for FITSNews, an independent news outlet in South Carolina, and later producing the Murdaugh Murders podcast, Matney was dogging this story from the beginning, raising questions about other deaths related to the powerful family. Nobody was in a better position to report on the murders when they occurred.

In “Blood on Their Hands” (William Morrow, $28.99), cowritten with Carolyn Murnick, Matney recounts her experience covering the case. And along the way she charts the trajectory of her career starting out as a young, inexperienced journalist writing about petty crime for the Hilton Head Island Packet to covering one of the biggest crime stories of the decade.

Suzanne Van Atten is a book critic and contributing editor to The Atlanta Journal-Constitution. You can contact her at Suzanne.vanatten@ajc.com.

About the Author

Keep Reading

The Latest

Featured