I don’t think there’s anything that shatters a community of friends and family more than a suicide among its ranks. In addition to being grief-stricken over their loved one’s death, survivors are often tormented by the questions of why they did it and what could they have done to stop it.

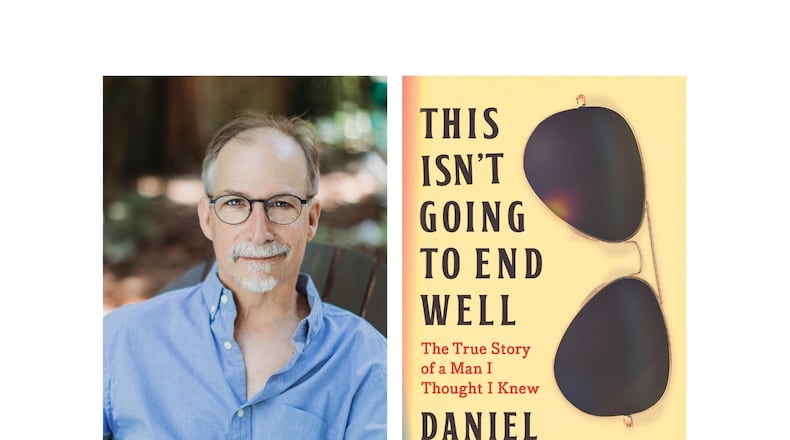

The answer to that last question seems to be nothing in Daniel Wallace’s gripping memoir “This Isn’t Going to End Well” (Algonquin, $28). In fact, by the time you get to the end — which, if you’re like me, will be the day after you start it because I literally couldn’t put it down — you realize what a tremendous effort it took for William Nealy to live as long as he did.

A native of Birmingham, Alabama, and a professor of English at the University of North Carolina, Chapel Hill, Wallace is best known for his 1998 novel “Big Fish,” which was made into a hit movie and a Broadway show. His first foray into nonfiction is as much a biography as it is a memoir because Wallace focuses less on himself and more on Nealy, a man Wallace grew up admiring and emulating.

Wallace was 12 years old in 1971 when he first met his big sister Holly’s boyfriend and future husband. Nealy was a good-looking, confident daredevil with long blonde hair, broad shoulders and aviator glasses who seemed to know everything about everything, especially pertaining to the natural world. Wallace would pattern his formative adolescent years after Nealy and credits the man for his career as a writer.

“Every book I’ve written is dedicated to him in invisible ink,” Wallace writes. “I doubt I would have written a one of them without him, or that I ever would have considered being an artist at all.”

Wallace portrays himself as an aimless, languid teen who spends his time getting high, hooking up with girlfriends and dreaming about being a writer, although he lacks the ambition to do anything about it. When Nealy, who develops an international following as an underground comic artist, turns his unparalleled knowledge about paddling the Southeast’s rivers into a successful publishing venture, Wallace is inspired to do something about his own aspirations.

“I thought of him as the child of James Dean, Albert Camus, Ernest Hemingway, Keith Richards, Satan, G.I. Joe and, of course, Clint Eastwood,” Wallace writes. “That was the part he played, anyway, that was the disguise he wore — courageous, sure, but not competitive, not aggressive.”

When Nealy kills himself in 2001 at age 48, Wallace’s admiration for the person who basically shaped him into the man he became turns to anger. In large part that anger is because Nealy left behind Holly, who was suffering with rheumatoid arthritis that attacked every part of her body from her hands and her feet to her heart and her lungs. She was helpless without her primary caregiver. Although it goes unsaid, it’s easy to imagine that Wallace was also angry because Nealy left him, too.

Wallace holds onto that anger until Holly’s death in 2011. That’s when he inherits Nealy’s meticulously maintained journals and discovers the secret of his brother-in-law’s tortured inner life. This isn’t the story of some big, dramatic reveal, but the slow, unfurling of a deeply troubled mind drowning in despair.

We’ll never know how much Holly knew of her husband’s mental state, but we’re not surprised Wallace was in the dark. The lack of depth in male friendships has been a recurring topic among pop psychologists in recent years, and Wallace’s friendship with Nealy could be a prime example.

“William didn’t share very much information about his life either and I didn’t ask for any, and maybe this is where the ground rules for the rest of our lives were set: Don’t ask questions. Talk as sparingly as possible. Do something, do anything, instead. So we would play pool, ride bikes, drink, smoke, do drugs, play music occasionally, go to bars, fish. But not much in the way of talking.”

Nealy is such a complex and fascinating person, his story securely anchors the narrative here. But the emotional weight Wallace conveys in his boyish love for Nealy, his bitterness over Nealy’s death and his eventual arrival at a place of empathy is what makes this memoir resonate.

Ultimately, “This Isn’t Going to End Well” is a story about the difference between the person we present to the world and the person we really are. It’s the gap between those two versions of ourselves that Wallace mines in this warts-and-all love letter to male friendship.

Credit: Handout

Credit: Handout

Townsend Prize winner announced

The winner of the 2023 AWC Townsend Prize for Fiction is Sanjena Sathian for her novel, “Gold Diggers.” The prize was awarded to her at a ceremony at the Atlanta Woman’s Club’s Wimbish House on April 13. The Atlanta author’s acclaimed debut novel focuses on suburban Atlanta teens Anita Dayal and Neil Narayan, who, in the words of our reviewer Anjali Enjeti, ”feel crushed by the weight of their Indian parents’ Ivy League-sized expectations and cope in troubling and dangerous ways.” Enjeti calls the book a “dazzling tale” that “crackles with sarcasm and wit.”

Suzanne Van Atten is a book critic and contributing editor to The Atlanta Journal-Constitution. Contact her at svanatten@ajc.com.

About the Author

Keep Reading

The Latest

Featured