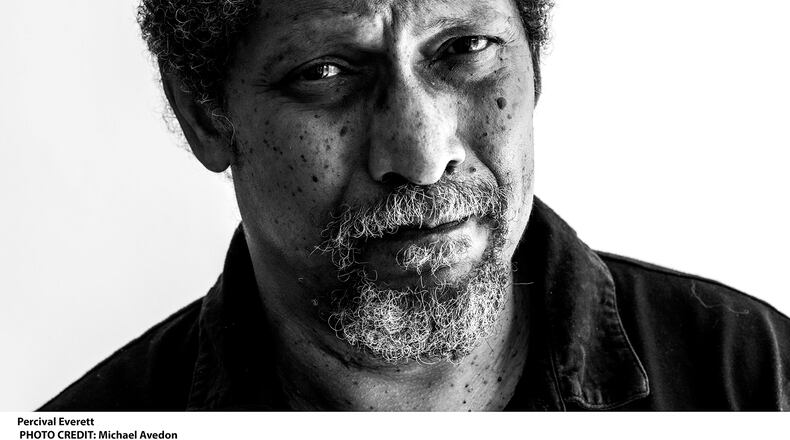

“James” by acclaimed author Percival Everett retells Mark Twain’s 1885 classic “Adventures of Huckleberry Finn” — as experienced by Huck’s enslaved travel companion, Jim. As Jim and Huck voyage up and down the Mississippi River, usually together but sometimes apart, Everett’s vision of Jim’s journey toward freedom is as much a harrowing adventure through the antebellum South as a vibrant depiction of an iconic literary figure tenderly rendered with heart and agency.

Everett’s brilliant and searing 2021 Booker-shortlisted novel “The Trees” is a satirical horror-comedy portraying gory ramifications of the 1955 lynching of Emmett Till that was heralded by The Guardian as “an act of literary restitution.” While Everett employs a gentler approach in “James,” using nuance and vulnerability to emphasize Jim’s humanity, he leaves a similar stamp on the literary landscape as he dismantles the stereotypes of the enslaved humans depicted in Twain’s classic.

The opening pages of “James” showcase the first point of difference between Everett’s and Twain’s “Jim” character by tapping into a notable aspect of the classic itself — the language. “Huckleberry Finn” was one of the earliest works of American literature to be written in the vernacular. A proliferation of racial slurs and stereotypical depictions consistently land the novel on the American Library Association’s list of most banned and challenged books.

Employing a first-person patois similar to “Huckleberry Finn’s,” Everett turns Twain’s use of dialect on its head as he shows Jim, and others who are enslaved, code-switch in front of the slaveowners to appear less threatening. “White folks expect us to sound a certain way and it can only help if we don’t disappoint them,” Jim explains to a group of children while teaching a lesson on “slave speech.” He also educates the children on the psychology required to remain safe, such as never offering a helpful suggestion or appearing to have an idea first. It provides an immersive plunge into the mindset used to survive slavery that is as infuriating as it is effective.

Credit: Handout

Credit: Handout

As in Twain’s tale, Jim is running to avoid being sold and separated from his family — wife Sadie and daughter Elizabeth. And Huck fakes his own death to flee his abusive father. They encounter each other on Jackson Island, have entanglements with a floating house, a steamboat, and two swindlers proclaiming to be a duke and a king, to name but a few parallels shared by Twain’s narrative and “James.”

The most notable difference in the storytelling is the stifling, palpable fear that accompanies Jim’s “adventure.” Jim is running not only for his freedom but his life, and the threat of capture equally fuels and foils his journey.

Everett paints a portrait of the realities required to uphold the institution of slavery as Jim encounters a variety of scenarios along the way. There are whippings, lynchings, breeding farms and rape. But in addition to being a truthteller, Everett is a satirical genius who employs a subtle hand to highlight the absurd as well.

After their raft is busted and Jim and Huck are separated, Jim washes up on the shore and is informed by four Black men he’s in Illinois — a free state. His hopes are destroyed, however, as the men explain they’re still enslaved because “the white folks around here tell us we’re in Tennessee.” None of the satire shines quite as bright as the ridiculousness of Jim being sold to a minstrel show, where he must paint himself white before applying blackface and is put in danger because his “wig” appears authentic.

Jim and Huck are separated a few times and while Huck goes off and has his own adventures, Everett’s narrative follows Jim and occasionally dips into the surreal. While recovering from a rattlesnake bite, Jim’s visitation from the 18th century French philosophizer Voltaire sparks a debate as Jim pokes holes in the famed abolitionist’s antiquated concept of civil liberties. Feverish and unaware that Huck has returned and he is speaking out loud, Jim fails to code-switch to slave speech and Huck’s suspicions are aroused.

Voltaire isn’t the only historical figure who makes an appearance in “James.” John Locke, the 17th century “father of liberalism,” and a few other prominent Age of Enlightenment scholars provide an intellectual think-tank for Everett to challenge how their doctrines allowed slavery to proliferate.

But the primary relationship explored in “James” is the bond between Jim and Huck. Huck is fascinated with Jim and seeks to understand their differences, most notably why Huck is free while Jim is enslaved. Huck is challenged because his natural instinct isn’t to perceive Jim as different, despite the messaging hammered into him by the surrounding world.

The bond Jim and Huck share goes both ways. After one of their separations, Jim admits he’s simultaneously “sick with worry over Huck and ashamed to feel such relief for being rid of him.” Their relationship proves even more complex once Jim must decide who to save from drowning: Huck or a friend who has offered him safety. Their storyline concludes with a compelling twist certain to inspire debate.

In a 2023 Publishers Weekly interview, Everett stated he set out to write “a novel about Jim, not about slavery. He happens to be a slave, but it’s about Jim, and about what Jim represents in the American literary landscape.” As Jim propels toward freedom and a reunion with his family — and ultimately his chosen name, James — it rapidly becomes clear Percival Everett has accomplished more than humanizing a marginalized voice. He has, once again, delivered a seminal work of literary reparation.

FICTION

“James”

by Percival Everett

Doubleday, 320 pages, $28

About the Author

Keep Reading

The Latest

Featured