Behind a stone wall on Briarcliff Road in Druid Hills sits huge, Gatsby-esque Briarcliff Mansion, now abandoned with boarded-up windows, home only to graffiti taggers and local wildlife. Nearby on the property is a foreboding, windowless building, just as empty, but occasionally the home of Hawkins Laboratory, scene of terrible experiments in the Netflix hit “Stranger Things.”

There is not much in this city stranger than the life and legacy of Asa Candler Jr., known in his day as Buddie, heir to the Coca-Cola fortune, former owner of the property and mansion, and a major wastrel and blowhard.

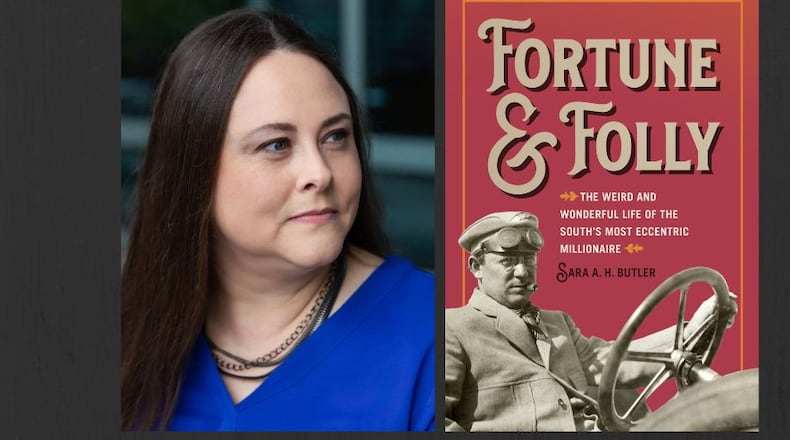

“Fortune & Folly: The Weird and Wonderful Life of the South’s Most Eccentric Millionaire” is the first biography of Candler. In it, Sara A.H. Butler, a director of product marketing at Cox Automotive who lives in Roswell, traces how, despite a penchant for messing up, Buddie Candler influenced and intersected with Coca-Cola, Emory University, Hartsfield-Jackson International Airport, Zoo Atlanta, West View Cemetery, and eventually, “Stranger Things.”

Candler was, as folks say today, a lot. Drawing on family letters and contemporary accounts, Butler presents a spoiled man-child who was, in her words, a “narcissist,” “punchline,” “high-spirited rascal,” “unruly” and a “fibber.” It’s clear she did not get too sympathetically close to her subject.

Butler is an excellent researcher and writer, and at around 240 pages, “Fortune & Folly” is a brisk, enjoyable read for local history buffs who want to fill in some areas not usually covered.

Asa Griggs Candler Jr. was born in 1880, one of four sons of Asa Sr. and Elizabeth Candler. It was Asa Sr. who bought John Pemberton’s formula for a fizzy soda fountain drink in 1888 and built it into an extremely profitable company.

Buddie, as Asa Jr. was called, went to Emory College, which was a small, all-male Methodist campus in Covington back then. He was in perpetual trouble, skipping class, smoking, smuggling a goat into a belfry. The yearbook named him “Class Pugilist.”

Butler can be a bit vague sometimes, but it appears that is because the source material, mainly letters, is vague. She writes that in college he “fell into the sweet embrace of vice,” which leaves a reader wanting a lot more detail. But there is little doubt about her conclusions. In an interview late in life, Buddie himself said: “If I experienced qualms about moral laxity, I stifled them.”

Not like his older brother Howard. Howard and Buddie were a case study in one popular theory of birth order. Howard was the first born, always responsible, a born hall monitor. Buddie was the second son, a rebellious agent of chaos. Even a century after they made their mark on Atlanta, Howard’s mansion, Callanwolde, is still an important part of Atlanta’s arts scene, while Buddie’s mansion, Briarcliff, is an empty shell.

Buoyed by the family fortune and his father’s attempts to find a place for him, Buddie bounced somewhat randomly through ventures and adventures.

In 1909, he and businessman Edward Durant (with help from Coke money) built the Atlanta Speedway, a 30,000-seat auto racing course south of the city designed to rival the Indianapolis 500. Big names came to race, people came to watch, but the business was poorly managed and failed, as happened frequently for Buddie.

Then his enthusiasm turned to aviation. He repurposed the racetrack into an airfield, which became Candler Field in 1925. A few years later, an Atlanta city alderman named William Hartsfield pushed through a deal for the city to buy the airfield from the Candlers. Buddie had unintentionally set up one of the major economic engines for Atlanta’s growth.

Another enthusiasm was starting his own private zoo. In the ‘30s he bought a menagerie including elephants, tigers and monkeys from a farm, shipped them to Atlanta and marched them through the residential streets of Druid Hills to Briarcliff Mansion, where he set them up in cages on his vast front lawn. An Atlanta Constitution reporter who covered the parade quoted Buddie’s brother Walter: “This is the biggest fool thing you’ve done yet.”

He named it Briarcliff Zoological Park and started charging the public 25 cents admission. But soon neighbors claimed the animals sometimes escaped and roamed the neighborhood, and within two years, the zoo was losing money. He sold the animals to the Grant Park Zoo, which eventually became Zoo Atlanta.

The name Briarcliff, now plastered over swaths of Dekalb County thanks to Buddie, came from one of his many cars. The Lozier Briarcliff H model, a high-end luxury car that Buddie loved, was named, in turn, after a road race in Briarcliff Manor, New York.

There’s much more; after all, Buddie was a lot. The book includes cameos by Ty Cobb, Harry Houdini, Charles Lindbergh and the Atlanta Crackers; Buddie’s obsession with magic; and his yacht being busted by U.S. Customs during Prohibition for smuggling huge quantities of booze from Haiti. So much of what he tried failed, and his whole life has an air of sadness rather than excitement.

In June 2022 Emory proposed reviving Buddie’s 42-acre Briarcliff property as a mixed-use senior living community. As with so many of Buddie’s own plans, it was announced with great fanfare. And as with so many of Buddie’s plans, it remains to be seen if the plan will ever come to fruition.

NONFICTION

By Sara A.H. Butler

University of Georgia Press

240 pages, $25.95

About the Author

Keep Reading

The Latest

Featured