Part of a sea change in the art world, artists like Jordan Casteel, Jerrell Gibbs, Amy Sherald, and Atlantans Gerald Lovell and Jurell Cayetano have made a radical reinvention of portraiture by introducing Black subjects and a Black point of view. It has been transformative, paradigm-shifting work. It’s also not necessarily new, if you consider the marvelous, revealing Spelman College Museum of Fine Art exhibition “Black American Portraits.”

Credit: photo © Museum Associates/LACMA

Credit: photo © Museum Associates/LACMA

This stunning distillation of how Black people look when seen through a Black artist’s eyes ranges far and deep. A treasure trove of subjectivity, this exhibition is a reminder of the paucity of complex, diverse representations of Black subjects in too much of art (and American) history.

Curators Liz Andrews and Christine Y. Kim envisioned “Black American Portraits” as a response to the influential exhibition “Two Centuries of Black American Art” curated by artist and historian David Driskell for the Los Angeles County Museum of Art in 1976.

Credit: Courtesy of Spelman College Museum of Fine Art/Renee Cox

Credit: Courtesy of Spelman College Museum of Fine Art/Renee Cox

“Black American Portraits” also originated at LACMA and includes sculpture, video, painting, photography and more and incorporates work from the 1800s to the present. Art royalty like Elizabeth Catlett, Jacob Lawrence and Charles White are featured alongside contemporary art stars like Mickalene Thomas and Kara Walker and anonymous artists and self-taught seers like the former inmate granted clemency by Barack Obama, Fulton Leroy Washington, whose photorealistic memorialization of Kobe Bryant “Shattered Dreams” is featured.

Some of the joys of “Black American Portraits” include three winking self-portraits by artist Barkley Hendricks. Known for his monumental paintings in the ‘60s and ‘70s of me-decade hipsters expressing a thrilling degree of bravado in their posture and fashion choices, Hendricks’ work feels as fresh and outrageously groundbreaking as the Kehinde Wiley around the corner.

Spelman College Museum of Fine Arts executive director Andrews co-curated “Black American Portraits” with Tate curator-at-large Kim while both were at LACMA. But significant shifts have been made for its present Spelman iteration.

Some of those changes enhance the unique charms of this venue and feature new combinations of works like a melancholy grouping of black and white images of mothers and children that conveys how one of society’s most cherished institutions, motherhood, has been dogged by unspeakable worry and undercut by anticipatory pain.

Credit: ©sheilapreebright

Credit: ©sheilapreebright

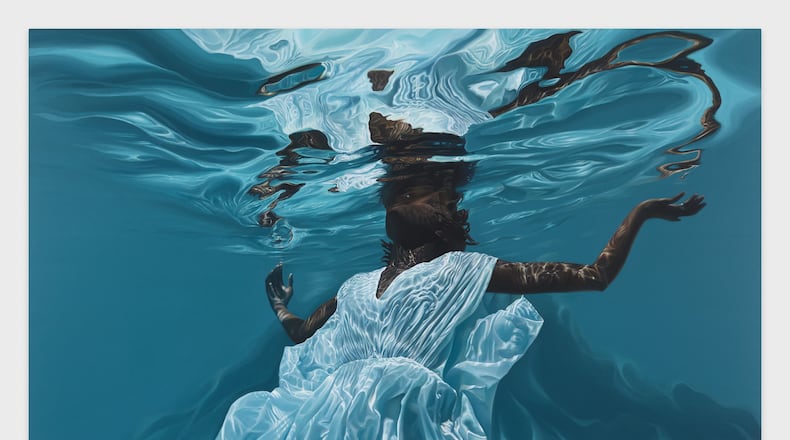

The exhibition’s Atlanta phase also draws from Spelman’s own collection just as the LACMA version leaned into its holdings. Atlanta-based photographer Sheila Pree Bright’s photo of Stacey Abrams (a Spelman alum), glimpsed in shadow from the back seat of a sedan and Calida Rawles’ painting “Thy Name We Praise” are both new acquisitions that, along with the Spelman space, give this iteration a warmth and intimacy that feels pleasantly distinct from the more familiar ethos of the white cube museum or gallery standard.

Credit: Courtesy of Spelman College Museum of Fine Art/photo by Joseph Hyde

Credit: Courtesy of Spelman College Museum of Fine Art/photo by Joseph Hyde

The work in “Black American Portraits” is myth-busting, from Amy Sherald’s Black surfers relaxing on the beach in “An Ocean Away” (2020) to a late 19th century daguerreotype of a regal unknown woman whose bearing and elegant clothing offer a historical vision of something other than slavery’s degradations. It feels similarly shocking to see an oil painting of a poised, broad-shouldered man with a nattily tied neckerchief, a soft sunset and sailing ship visible behind him in “Portrait of a Sailor” circa 1800, artist unknown. That sense of unflappable dignity continues in Sadie Barnette’s paired images of her father, in 1966 as a soldier and then in 1968 as a Black Panther surveyed by the FBI; the spectrum of service is undeniable, to country and to race.

Credit: photo © Museum Associates/LACMA

Credit: photo © Museum Associates/LACMA

The power of the show is in those juxtapositions of the historic and the distinctly contemporary epitomized in Barnette’s work that create a cumulative mix of wonder, outrage, tenderness and relief at all the misrepresentations and crimes that this show addresses.

This expansive exhibition taps a distinctly democratic, humanist vein with shades of Edward Steichen’s proto-blockbuster “Family of Man” at MoMA in 1955. It’s almost too much: too much to take in, too much pain, too much joy.

VISUAL ART REVIEW

“Black American Portraits”

Through June 30. Noon-5 p.m. Wednesdays-Saturdays, Suggested donation $5. Spelman College Museum of Fine Art, 350 Spelman Lane SW, Atlanta. 404-270-5607, museum.spelman.edu.

Bottom line: A simple concept yields extraordinary results in this contemplation of Black identity that fills an art history void with a cup that runneth over.

About the Author

Keep Reading

The Latest

Featured