Among the thousands of images left behind by America’s biggest sporting event, a few live on as indelible. During this week leading up to Super Bowl LIII in Atlanta, we look back daily on a select precious moment and appreciate the story behind it. Fourth in a seven-part series.

The NFL’s winningest coach was also, once upon a time, the Super Bowl’s most unfulfilled coach.

Back when this game was young, back when it was just a collection of Roman numeral I’s, someone slapped a “kick me” sticker on Don Shula’s back and it was years before he was able to reach it and rip it off.

By the time his unbeaten Miami Dolphins made it to L.A.’s Memorial Coliseum in early 1973, his was an entire team looking for a sense of completion. For all of them, it wasn’t so much about putting the fine point on the NFL’s only unbeaten season, it was about rinsing the bitter taste of big games past. Just the year before, Miami arrived at its first Super Bowl, only to be trashed by Dallas 24-3.

More on the series

» 1967 Super Bowl: A cigarette and a Fresca

» 1998 Super Bowl: John Elway goes helicopter

» 2008 Super Bowl: The helmet catch

» 1969: Super Bowl: The poolside guarantee

And when the Dolphins got past the Washington Redskins 14-7 in Super Bowl VII, surviving kicker Garo Yepremian’s famous spasm/pass attempt, they’ll insist that it wasn’t about perfection. “What felt so great was redemption,” vintage Dolphins lineman Manny Fernandez told The Atlanta Journal-Constitution, “after having gotten our butts spanked the year before. It was about winning that Super Bowl, getting back there and winning. That’s what was on our mind – not being embarrassed again. The worst feeling in the world, I think, is losing a Super Bowl.”

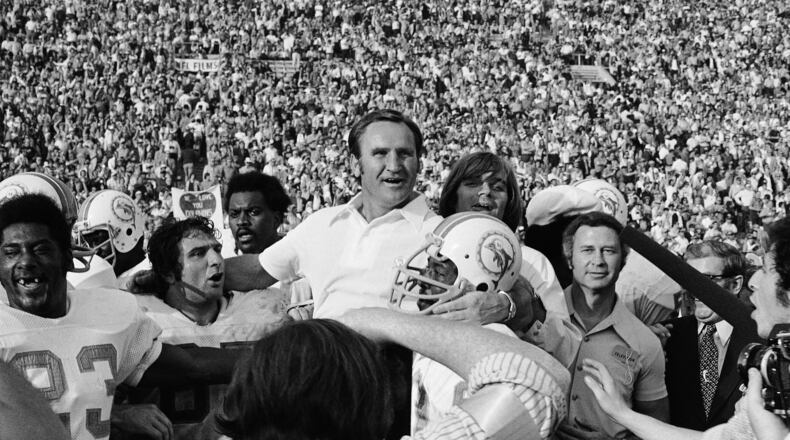

As Shula was hoisted upon his players’ shoulders afterward – striking the classic pose of the emperor/coach leaving the field in victory – the image was made all the more meaningful by the coach’s difficult personal relationship with these ultimate games.

You could go back to before there was a Super Bowl, back to when Shula coached the Baltimore Colts. Heavily favored in the 1964 NFL Championship, Shula’s Colts were upset by Cleveland.

There was the 1972 loss by the not-quite-ready-for-primetime Dolphins. But trumping any Super Bowl disappointment past or present had to be Super Bowl III, the game that made Joe Namath famous, that changed the face of the NFL and, as it turned out, that was a very beneficial for the Dolphins.

“It brought (Shula) to us, which was a good thing,” Fernandez said.

You know the deal: Shula’s Colts roll into the game heavily favored over a New York Jets team from the upstart AFL; Jets quarterback Namath guarantees victory; world scoffs; Jets win anyway proving the idea to merge NFL and AFL not so daft after all.

Every full moon has a dark side. Every hit has a “B” side. There, after one of the most widely celebrated Super Bowls of them all, you would find Shula. (A little more vinegar on the wound: Baltimore finally won its Super Bowl, No. V, the year after Shula left for Miami).

Shula carried with him to Miami the weight of losing the game no one this side of Namath thought possible to lose. As he told Don Banks in Fansided.com in 2016: “Super Bowl III was just such a disappointment, being so heavily favored and seemingly everything was pointed in our direction, and then to fail.

“And that failure kept getting brought up and it wouldn’t go away. There were a lot of New York people that really enjoyed that. It’s just a bad memory. So, I had to learn to live with it and I couldn’t do anything about it until we did something about it.”

So that explains the look of utter satisfaction on the coach’s countenance as he rode the shoulders of his players. Why, that might even be a small smile breaking out north of that cowcatcher of a chin, softening the stern coaching mask Shula so often wore.

Mission accomplished. “The whole season was pointed at getting back to the Super Bowl and winning it,” said Fernandez, who had 17 tackles against the Redskins. He’s retired these days to the small central Georgia town of Ellaville. Shula and his 347 career wins live in south Florida.

But perfection was nice, too.

“Nobody has done it since and nobody did it before. It just stands by itself,” Shula told Fansided.com.

If the image of Shula being hoisted in victory wasn’t enduring enough, the Dolphins committed it to bronze in 2010. Unveiled then outside their home stadium was an 11-foot statue of Shula, pumping a fist as he was borne by linebacker Nick Buoniconti and reserve lineman Al Jenkins.

Not depicted in the scene was the young man who in all the post-game confusion on the Coliseum field pilfered the watch right off Shula’s wrist while he was aloft.

Shula being Shula, he dismounted, caught up with culprit, and, just as he had done that day with his legacy, reclaimed what was his.

About the Author

Keep Reading

The Latest

Featured