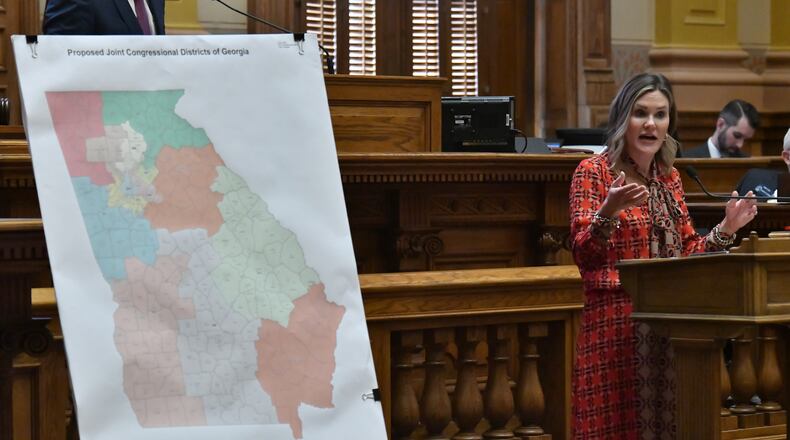

Redistricting in Georgia is done. Now come the lawsuits.

Opponents of Georgia’s new political maps plan to ask judges to throw them out as soon as Gov. Brian Kemp signs them into law.

The lawsuits will allege that the maps are racially discriminatory, according to voting rights organizations and redistricting experts. Critics of the maps say Georgia’s redrawn districts reduce the voting strength of people of color who accounted for the state’s population growth over the past decade but could lose representation after next year’s elections.

Georgia is the No. 1 state to watch for new redistricting or voting rights litigation, said Marc Elias, a voting rights attorney who frequently represents the Democratic Party.

“The maps produced out of the special legislative session block Georgia’s communities of color from obtaining political representation that reflects their population growth,” said Jack Genberg, senior staff attorney for the left-leaning Southern Poverty Law Center. “Implementing political maps that undermine the voting power of communities of color is unlawful.”

Racial discrimination in redistricting is illegal under the Voting Rights Act of 1965, but the U.S. Supreme Court has upheld redistricting for partisan purposes. The challenge for plaintiffs will be to prove redistricting was discriminatory and not just political.

Republican legislators who support Georgia’s new maps say they’re fair and legal, with equal populations in each district.

House Speaker David Ralston said other states controlled by Democrats, such as Illinois, Maryland and New York, have manipulated redistricting for their political advantage.

“You never hear those talked about — the blatant abusive use of the political process — but it’s a part of the process, and I don’t know how you take it out,” said Ralston, a Republican from Blue Ridge. “I think the maps, notwithstanding the rhetoric, are fair. They very carefully followed the law. They follow the Voting Rights Act. Now we’ll see what happens.”

Lawsuits could point to several examples in Georgia’s new maps where Black voting strength was weakened.

In the 2nd Congressional District in southwest Georgia, represented by Black Democratic U.S. Rep. Sanford Bishop, the area’s new map shrank the Black population from 51% to 49%. In the 6th Congressional District held by Black Democratic U.S. Rep. Lucy McBath, legislators increased the district’s white majority to 64%, making it lean heavily Republican.

On the state level, several General Assembly districts could also be challenged, including a Johns Creek district held by state Sen. Michelle Au, the daughter of Chinese immigrants. The redrawn Senate district became less racially diverse and now favors Republican candidates after Democrat Joe Biden won 59% of its vote last year.

Aklima Khondoker, chief legal officer for the New Georgia Project, said Georgia’s Republican majority in the General Assembly created maps that tilt the balance of power away from Black voters who have been historically disadvantaged in elections.

“Any shift that dilutes the voting strength of people of color sets up alarms,” Khondoker said. “It’s crystal clear to me that the line between political gerrymandering and racial gerrymandering is actually the same line. We cannot pretend that these things are exclusive from one another.”

Unlike past redistrictings, opposition to Georgia’s political maps will go straight to the courts because a 2013 U.S. Supreme Court ruling brought an end to federal oversight. Before the decision, states with a history of racial discrimination, including Georgia, were required to obtain federal preclearance before new districts could go into effect.

“It’s become much more difficult right now,” said Charles Bullock, a University of Georgia political science professor who wrote a leading book on redistricting. “It’s expensive and time-consuming, and if there’s an appeal directly to the Supreme Court, your odds of getting heard are not at all good.”

Still, some cases have been successful over the past decade based on claims that minorities were overconcentrated, including in Alabama, North Carolina and Virginia, Bullock said. The last Georgia case alleging the state’s congressional maps harmed Black voters was dismissed last year.

House Speaker Pro Tem Jan Jones said Democrats are being “misleading and disingenuous” when they criticize individual districts without taking into account population changes throughout the state that required changes to ensure equal populations in congressional, state House and state Senate maps.

Georgia’s population grew by 1 million over the past decade to a total of 10.7 million, according to census data. The increase in Georgia residents was entirely among people of color as the state’s white population slightly declined.

Black Georgians overwhelmingly support Democratic candidates. A majority of white voters in Georgia support Republicans in most of the state.

“As a member of the majority party, I’m willing to call it for what it is. The map before you is a fair, legal map, and one that clearly reflects changes in population,” Jones, a Republican from Milton, said during a House debate on congressional maps.

While lawsuits are certain, their timing isn’t.

Kemp has 40 days after the General Assembly adjourned to sign Georgia’s redistricting bills — until Jan. 1. Lawsuits could be filed immediately afterward.

About the Author

Keep Reading

The Latest

Featured