On a sunny Florida Sunday 20 years ago, one bizarre allegation turned the nation’s partisan divide into an irreparable chasm.

Republicans accused Democrats of eating the evidence of election fraud.

This was November 2000, midway through a recount of Florida’s votes in that year’s presidential election. With the outcome settled in every other state, Texas Gov. George W. Bush led Vice President Al Gore by a sliver of votes in Florida, and the state’s winner would assume the presidency.

The contentiousness of the 36-day recount presaged decades of controversy in American politics: a perpetually gridlocked Congress, a divisive war based on faulty intelligence, a presidential candidate’s missing emails, Russia’s interference in U.S. elections, the era of alternative facts, an impeachment — and, now, a ballot-by-ballot statewide recount in Georgia in response to unsubstantiated claims of election improprieties.

Georgia’s recount differs from Florida’s in many key respects. Bush led Gore by fewer than 1,000 votes in Florida when the recount began in 2000, and he ultimately was declared the winner by 537 votes.

In Georgia, former Vice President Joe Biden had a margin of more than 14,000 votes over President Donald Trump headed into the recount. On Friday, national media outlets declared Biden the state’s winner.

Most significant, even if Trump somehow gained enough votes to overtake Biden in Georgia, the Democratic candidate already has enough electoral votes from other states to easily win the election.

Still, an examination of the 2000 recount offers insight into what Georgians can expect during the next several days, as officials in all 159 counties re-examine nearly 5 million paper ballots, one at a time. Like Florida’s recount, the exercise could easily devolve into wild accusations that further undermine confidence in the results.

“It’s going to take a while to get through this,” said Aubrey Jewett, a political scientist at the University of Central Florida who has researched the 2000 recount. “People just need to have patience and not let their emotions get the better of them until it’s done.”

‘Fallen chads’

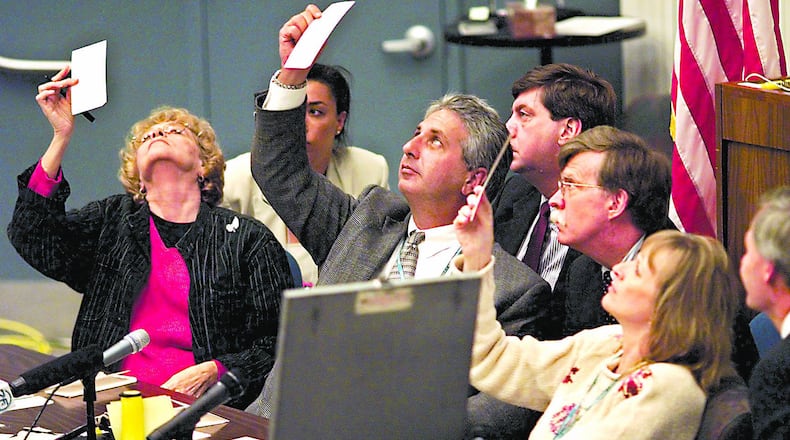

On Sunday, Nov. 19, 2000, officials in heavily Democratic Broward County painstakingly examined the punch cards that were supposed to reveal each voter’s choice in the presidential race. But voters who hadn’t pushed a stylus completely through the card left behind a tiny dot of paper still attached to their ballots.

A hanging chad.

In Broward and three other counties where the recount was initially ordered, officials peered endlessly at some punch cards, looking for evidence of a voter’s intent. Some counties awarded votes only for chad-free ballots. Others counted ballots with hanging chads or even those on which voters left only a protruding mark — a so-called “dimpled” or “pregnant” chad.

In all their forms, chads became the source of both controversy and jokes. But at Broward’s cavernous emergency command post, normally used to monitor hurricanes and other natural disasters, two Republican observers signed affidavits claiming the chads were evidence of a crime.

The observers said they witnessed Democratic vote counters poke holes in ballots to indicate votes for Gore — and then swallow what a Republican official later called the “fallen chads.”

Outside the command post, a Bush campaign spokesman named Ken Lisaius reached into the inside breast pocket of his navy blue blazer for a zip-lock baggie that contained 142 chads that he said Republican observers had retrieved that day.

“I wouldn’t even want to hazard a guess,” Lisaius said, “as to why someone would choose to eat chad.”

The allegation was never resolved. Other matters — including whether the recount would be conducted statewide — soon took precedence, and each new development attracted intense scrutiny. At one point, C-SPAN aired nearly three minutes of live footage of clerks from Palm Beach County faxing vote counts to the secretary of state’s office in Tallahassee.

And both political parties tried to sway public opinion, flying in senators, governors, members of Congress and celebrities to recite talking points for the television cameras.

On the last weekend of the recount, these surrogates for the presidential campaigns held almost continuous press conferences in the parking lot outside Palm Beach County’s emergency center, where ballots were being examined. The Rev. Al Sharpton spoke on Gore’s behalf, minutes before Rudy Giuliani appeared for Bush.

‘Without merit’

Florida’s secretary of state ended up certifying the election — with Bush ahead by 537 votes — with the recount still under way in populous and heavily Democratic Palm Beach County.

State courts then ordered a recount in all of Florida’s 67 counties, but the U.S. Supreme Court put an end to the process on Dec. 9, effectively deciding the election in Bush’s favor. Gore conceded defeat on Dec. 13.

Even though Bush sought to end the recount, the lawyer who led his efforts in Florida says Gore raised legitimate issues.

“Those ballots were very problematic,” attorney Barry Richard of Tallahassee said in an interview Friday. “Every time you ran them through the machine, chads would fall out.”

This year, however, Richard sees no reason to contest the outcome.

Lawsuits filed on Trump’s behalf, most of which have been summarily dismissed, were “completely without merit,” Richard said.

And he thinks Georgia’s recount, like Florida’s two decades ago, won’t significantly affect the vote totals.

“Even if it shifted,” he said, “it wouldn’t make any difference in who the winner is.”

But Jewett, the University of Central Florida political scientist, said verifying the vote totals could narrow the gap between Democrats and Republicans.

“A lot of Georgians are questioning the validity of this election,” Jewett said. “To do a recount and to expel any of these claims hopefully will give people even on the losing side more confidence in the result.”

Our reporting

Reporter Alan Judd covered Florida’s recount of the 2000 presidential election for The Atlanta Journal-Constitution. Before joining the AJC in 1999, he wrote about state government and politics for Florida newspapers.

About the Author

Keep Reading

The Latest

Featured