New school, deep roots

In far west Atlanta, in a curve where two interstates connect, on a Collier Drive corner across from a Baptist church, stands Harper-Archer Elementary School.

The school is tied to this spot by concrete and history, a community anchor since it opened in 1963.

VIDEO: About Harper-Archer Elementary

Back then, back at the beginning, it was Harper High School. And to Artie Cobb, it was a beautiful, modern building where he and his classmates were the first to leave their mark.

He was struck by the building’s futuristic design, unlike the brick high schools that came before.

“Everything was first class; there was nothing second class. And it was the first time that I had attended high school that we did not get books that were coming from a white school. They were all new books,” he said.

The school opened in January, 1963. Cobb transferred in mid-way through his junior year and was a member of the first class in 1964.

The district had determined it needed the high school to accommodate a growing west-side population as middle-class African-American families moved into the area annexed into the City of Atlanta the decade before.

Both the school and community have changed since then. It lies amid the poorest 10% of Census tracts in Georgia, and the median household income is about half of the state’s median.

By the time Superintendent Meria Carstarphen arrived in Atlanta in 2014, the district was half the size it once had been. The city had faced an economic downturn, and housing projects had closed.

APS merged two elementary schools and converted the middle school into Harper-Archer Elementary. It opened in August with colorful murals featuring African-American pioneers such as Barack Obama, Gladys Knight and Frederick Douglass.

INSIDE HARPER-ARCHER: MORE STORIES

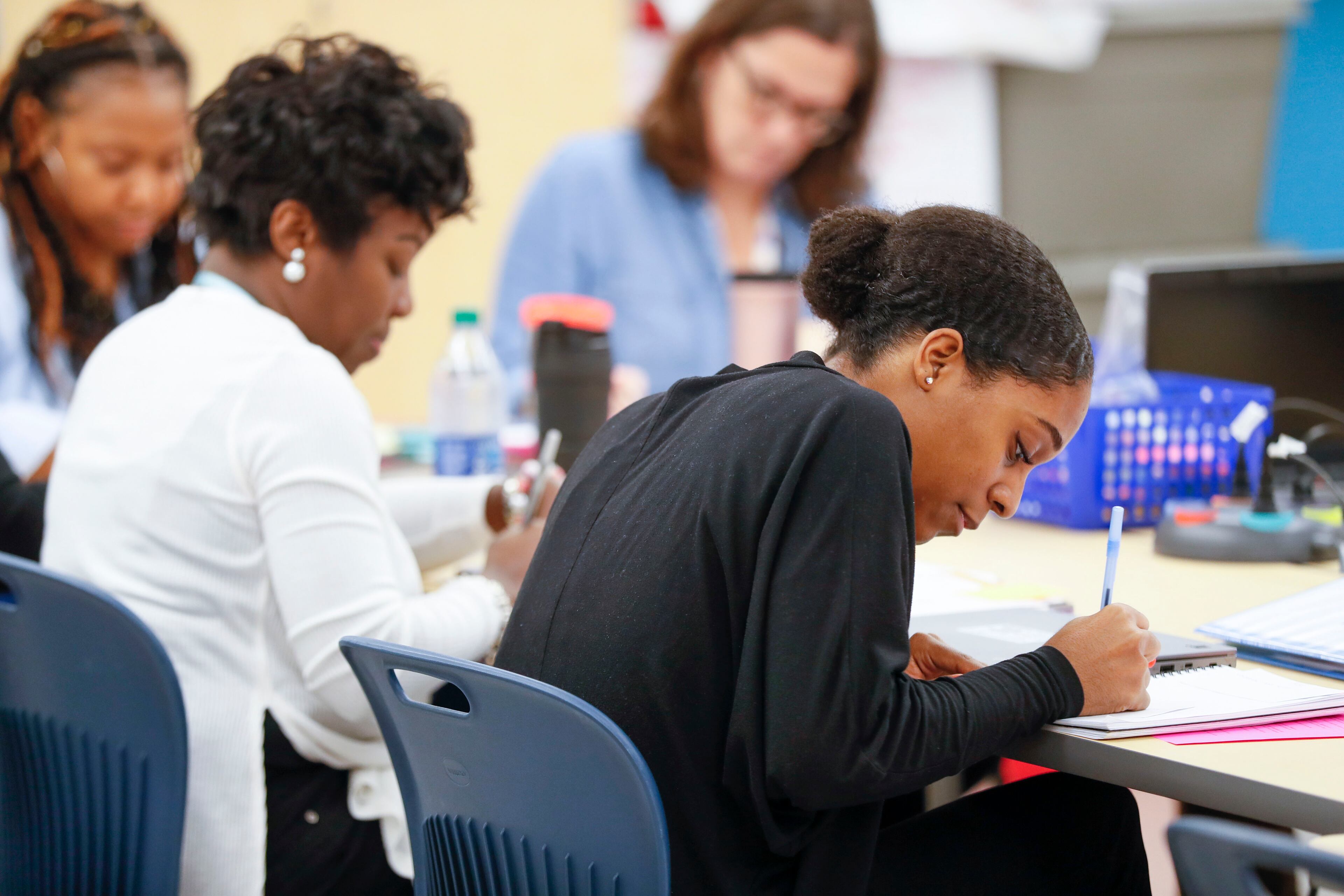

» Teachers try to fill academic, skills gap

This school year started with unrest in one of the apartment complexes where many Harper-Archer students live. In August, residents and a couple of Atlanta council members gathered outside to protest what they said were deplorable living conditions.

The school’s attendance zone includes stretches of Fulton Industrial Boulevard and Martin Luther King Jr. Drive, where fast-food restaurants, dollar stores and laundromats line the street.

Al Hunter, a real-estate broker who graduated from Harper High School in 1983, recalls when merchants lived in the community and many parents knew each other. He opened Community Realty in a shopping center near several loan businesses because he wanted there to be a “legitimate business that wasn’t hurting people” in the neighborhood.

As his generation grew older, people moved to the suburbs, he said. Now, many properties are rentals.

Residential streets curlicue around wooded lots, rolling up and down hills. Driveways lead to mid-century houses. Doors are barred for safety, a few windows, too.

On the same street, a pin-neat and freshly painted house shares a property line with a blue-tarped and crumbling neighbor.

The widespread gentrification that has altered other Atlanta neighborhoods while displacing lower-income residents hasn’t hit here.

INSIDE HARPER-ARCHER: THE PHOTOS & VIDEOS

» ‘You can always dance it out’

Some do see signs of change. Hunter said real-estate investors are taking an interest in the area, which has attracted first-time home buyers to neighborhoods conveniently located near I-285 and I-20.

He believes the success of the community and schools are linked: “It’s a partnership, and you have to have community involvement.”

Because it’s so difficult for families to escape deep poverty, Harper-Archer Principal Dione Simon Taylor feels a moral obligation to make sure the school has done everything it can to educate students: “If we do it right here, then we have a better chance of getting it right in the next generation.”

The school is trying to get outside groups and businesses to pitch in.

The school’s partnership and programs director, LaJuana Ezzard, has grown the number of partners working with the school from three to 50. They include supporters who assist with after-school programs and donors who help with literacy activities.

Unlike many schools in affluent communities, Harper-Archer doesn’t have its own foundation to throw flashy fundraisers. Ezzard said so far corporate sponsors, who have poured money into certain Atlanta schools, haven’t flocked to Harper-Archer.

In some schools, students just don’t have the same foundation for learning as others. It’s a problem Atlanta’s school district has been confronting for generations, and the district has been in a multiyear, multimillion-dollar project aimed at helping.

Some steps, such as turning six schools over to charter groups to run, have been controversial and watched nationally, since educational inequity is a problem all over the country, not just in metro Atlanta.

Teachers know that whatever they do in the classroom, they can’t control some factors – parental involvement and generational poverty, for example – that have powerful influence on their students’ ability to learn. Atlanta’s results so far underscore just how difficult turnaround is. Schools have seen some gains, but there’s minimal evidence it’s because of the turnaround investments.

The Atlanta Journal-Constitution wanted to know: Just how does the school give students the proper education they’ll ultimately need to compete with their peers for adequate jobs, and to be responsible, productive citizens in our communities?

To answer that question, we knew we had to be in the classrooms and hallways of a school trying to find solutions to these challenges.

We knew we had to speak to community residents and parents.

The AJC asked Atlanta school officials to give us unprecedented access to a school being targeted for special attention because of its long-standing challenges.

Harper-Archer Elementary, the “turnaround school” the district selected when the AJC proposed this project, is new. The west Atlanta school opened this year to serve neighborhoods that are among the poorest in Georgia.

School officials allowed our reporter and photographers a close-up view of the people and the everyday goings-on in the life of that school community.

Over several months, AJC reporter Vanessa McCray and photographers Alyssa Pointer and Bob Andres spent many days observing, interviewing and recording the efforts and the motivations of the dozens of people who are trying to ensure that what’s in store in the lives of the children there can be brighter than their beginning.

Successful communities support and invest in the education of children. Strong schools use that support to set high expectations and to execute bold, cutting-edge initiatives.

Not every school in Atlanta can claim such success. For some city schools, the challenges seem too great to overcome.

Students at Harper-Archer Elementary School come to class each day from Atlanta neighborhoods struggling with the harmful side effects of generational poverty. They also suffer from inconsistent parental engagement and many of these children lack basic reading skills – the foundation for academic accomplishment.

The Atlanta Journal-Constitution wanted to know, just how do teachers, principals, counselors, and other school staffers try to give these children the proper education they’ll ultimately need to compete with their peers for adequate jobs, and to be responsible, productive citizens in our communities?

Atlanta Public Schools gave the AJC unprecedented access to the inner workings of its efforts to turnaround this school. The stories inside this special section are the result of our reporter and photographers spending dozens of hours at Harper-Archer over several months.

If the folks at Harper-Archer are successful with their bold plans, the school will serve as a template for other urban schools struggling to meet basic standards.

We interviewed school leaders, teachers, community residents, and parents, to get the full picture of the magnitude of the challenge and of those who are trying to find solutions.

They are stories of determination and hope.

- Todd C. Duncan, Senior Editor Local Government and Education

She tells them: “You are entering a place where teachers love what they are doing, and it’s a joy to learn. But also more than anything, we are trying to build a legacy here.”

Cobb, president of the Charles L. Harper High School International Alumni Association, knows better than most the origins of that legacy. He remembers how Harper High had a home economics classroom with the most up-to-date kitchen appliances, air conditioning — a novelty at the time — and a demonstration area where students could voice political opinions.

More than a half-century later, at a November ribbon-cutting ceremony, he addressed the crowd gathered to celebrate the building’s reopening as an elementary school. The school represents the past, he said, and a foothold on the future: “Dr. Taylor, this is your house. Your house to keep, and your house to continue to build.”

» NEXT STORY: A principal’s day

The Harper-Archer name

Charles Lincoln Harper: Served as the first principal at Booker T. Washington High School, Atlanta's first public high school for African American students.

Samuel Howard Archer: Served as the fifth president of Morehouse College.

About Harper-Archer Elementary neighborhoods

The Atlanta Journal-Constitution analyzed Census tract data for the areas where students are zoned to attend Harper-Archer Elementary School.

Estimated median household income

Harper-Archer: $27,175

Atlanta: $55,279

Georgia: $55,679

Estimated percentage of population with bachelor’s degree or higher

Harper-Archer: 16%

Atlanta: 50%

Georgia: 31%