An outspoken and highly successful businessman, he has been described as an egotistical and irascible outsider who bristled at the political establishment, saying things not repeated in polite society while claiming to be the defender of average Americans during his unconventional run for president.

Donald Trump?

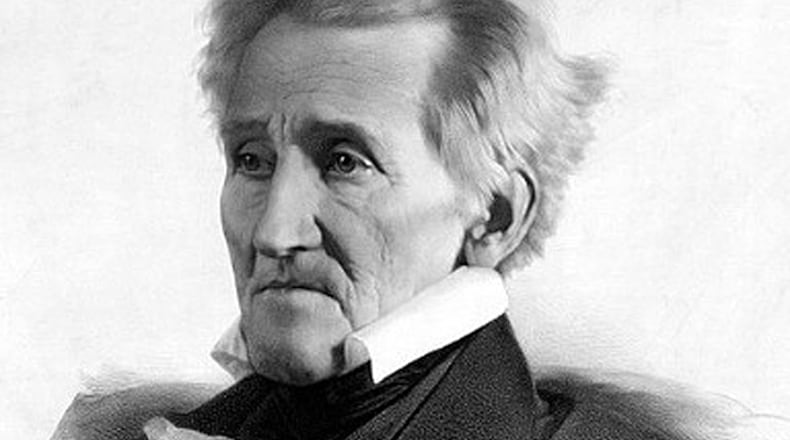

Try Andrew Jackson in 1828, the year the rough-cut Tennessean was elected to the White House after a nasty campaign that spun from one personal attack to another, seemingly on much the same track the current GOP slugfest has taken.

The Jackson parallel

In an emerging lesson from history, as billionaire real estate mogul Trump continues his push to capture the Republican nomination, political observers and experts liken the current break-the-mold race to Jackson's rise to the presidency 188 years ago.

"He was a boorish guy at a time when that was not tolerated in politics, who said what he thought and said whoever disagreed with him was wrong," said Brandon Rottinghaus, a political scientist at the University of Houston who specializes in presidential governance. "At times, when voters have elected an outsider, it has been a candidate who has been famous, a celebrity, who has the ability to command an audience. Andrew Jackson did that."

'The first populist'

Jackson, a famous general in the War of 1812, served as a governor, congressman and senator before unsuccessfully running for president in 1824, losing to John Quincy Adams, the well-educated son of the nation's second president.

Jackson came back four years later, backed by populist support to oust Adams after a nasty campaign marked by charges that his wife was a bigamist because she married Jackson years before her divorce — which she thought had been finalized — was complete. He also was criticized as a slave owner and for executing British soldiers while he was military governor of Florida.

The legend of 'Old Hickory'

A man of quick temper known for his fits of vengeance, Jackson — president from 1829 to 1837 — was once a social outcast and was legendary for brawling and dueling, including one duel in 1806 over his wife's honor where a bullet lodged too close to his heart to ever be removed. Though wounded, he shot and killed his opponent.

As he left Washington, he listed two regrets that reflected his blunt personal style: that he was "unable to shoot Henry Clay or to hang John C. Calhoun" — referring to two political opponents in Congress.

"Jackson's appeal was to less-educated people, the people who felt excluded and disenfranchised from the political establishment," said Michael Mezey, a political science professor at Chicago's DePaul University who is completing a book on presidential campaigns. "Jackson was the first of what was considered to be modern campaigning, where they went around handing out free booze and food and did rabble rousing to get elected. Trump has a populist message. Jackson may have been the first populist. He struck fear into the hearts of the establishment in Washington, and so does Trump."

Historical comparisons

In recent times, some scholars have also likened Trump's appeal to that of George McGovern, the Democratic Party nominee in 1972 who bested the party establishment with populist support, and to Ronald Reagan's unsuccessful 1976 run for the GOP nomination.

"The party establishment thought he was too extreme, and four years later the establishment thought he would pull the train off the rails, and that's why Bush was the establishment candidate," Rottinghaus said. "But Reagan beat him in New Hampshire ... and went on to win."

'Chickens coming home to roost'

Jeffrey Engle, director of the Center for Presidential History at Southern Methodist University in Dallas, noted: "What's happening now is amazing: So much of the Republican Party has been about trickle down and improving the middle class, and that success with the middle class is now driving the anger that is helping Trump.

"It's like the chickens are coming home to roost," he said, "and Trump is hijacking the party."

When Jackson was elected as the seventh U.S. president in 1828, he was accused by the establishment of hijacking American politics. He's been the face on the front of the twenty-dollar bill since 1928.

About the Author

Keep Reading

The Latest

Featured