Kentucky insurance exchange still leads the way

Sometimes the grass is blue on the other side of the fence.

Kentucky has set itself apart from its neighbors — and much of the rest of the country — as one of the few success stories to emerge from Obamacare’s calamitous roll out.

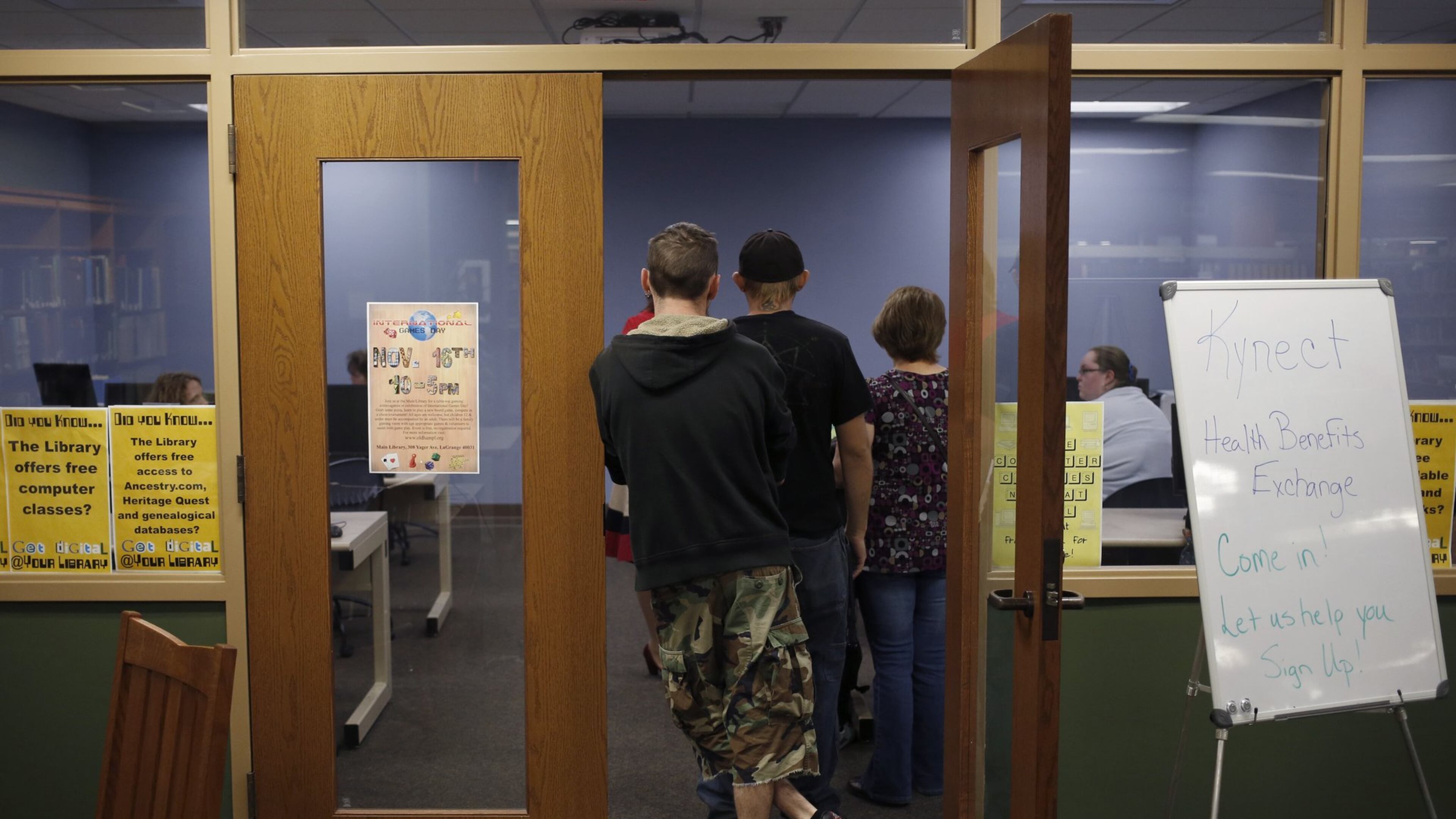

Roughly 60,000 Kentuckians have signed up for health coverage through the state-created insurance exchange, called Kynect, since its Oct. 1 launch. About 12,000 enrolled in individual insurance plans, and 48,500 in the state’s expanded Medicaid program, according to figures released this week.

Meanwhile, nearby states that left it up to the federal government to build their exchanges, including Georgia, have reported dismal enrollment numbers as technical breakdowns have continued to plague HealthCare.gov. During the exchange’s first month, only 536 Georgians enrolled in plans through the federal Health Insurance Marketplace.

In Kentucky, health officials have been quick to publicly tout Kynect’s rising enrollment — posting updated numbers each week. The Obama administration, on the other hand, has released enrollment data for the struggling federal exchange only once so far, in mid-November, and intends to update those numbers just once a month. New exchange numbers for Georgia likely won’t be available for at least another couple of weeks.

Hundreds of health insurance “navigators,” application counselors and insurance agents across Kentucky are busy fielding questions in person and over the phone. People from bordering states like Tennessee or Missouri have been calling, too, but they’re being told they have to use HealthCare.gov, said Regan Hunt, executive director of the nonprofit Kentucky Voices for Health.

“That’s all we can do,” Hunt said. “Everything (in this case) really is better on the other side.”

‘How we got Obamacare to work’

Kentucky is the only state in the South to build its own insurance exchange and also expand Medicaid — two elements of the health care law that are critical to its aim of insuring millions of Americans. Democratic Gov. Steve Beshear ordered Kynect’s creation without legislative action, circumventing any roadblocks from the state’s Republican Senate. Opponents and tea partiers tried but failed to pass a law barring the move and also sued, unsuccessfully, in federal court.

Providing the Bluegrass State’s 640,000 uninsured residents with coverage is a moral obligation, Beshear told The Atlanta Journal-Constitution in a September interview. He also saw implementing the law as something the state couldn’t afford not to do. Expanding Medicaid alone is expected to produce $15.6 billion in economic impact and create nearly 17,000 new jobs for the state, according to an independent study by the University of Louisville.

Not all the news out of the commonwealth is great, however. Kynect has worked better than other exchanges but some users have still run into technical problems. As in other states, Kentucky’s insurance plans also have narrower networks of doctors and hospitals than many people are used to. And Kentucky is one of the few states that required insurers to cancel current plans that don’t meet all of Obamacare’s standards.

But Beshear’s efforts have unquestionably placed Kentucky on the national stage. He recently joined the governors of Washington and Connecticut, which also have state-run exchanges, in penning an opinion piece in the Washington Post headlined “How we got Obamacare to work.”

The governor’s backing has been crucial to Kynect’s success, said Carrie Banahan, the site’s executive director. Providing more people with coverage is ultimately going to make Kentucky a healthier state, she said.

Banahan said she was excited to learn that more than 900 small businesses had enrolled in group coverage for their employees through Kynect. More than 300 more are in the process of selecting plans, she said.

Rejecting the Medicaid expansion

A few states have called to learn more about how Kentucky managed to achieve what the Obama administration could not. Georgia was not one of them.

Though Kentucky is smaller than Georgia, both states have in common unhealthy populations with some of the highest rates of obesity, smoking, diabetes and cardiovascular disease.

“We believe our rankings will improve and we’ll be able to increase the overall health care status for Kentuckians,” Banahan said.

Obamacare opponents in the state have raised concerns about whether Kentucky can afford to expand Medicaid and if it can successfully run an exchange. Kentucky Senators Mitch McConnell and Rand Paul have loudly criticized the health care law across their state and in Washington.

In Georgia, Gov. Nathan Deal, an ardent Obamacare opponent, has long said Georgia can’t afford to expand its ailing Medicaid health program for the poor. Expanding the program is estimated to cost the state upward of $2 billion over 10 years but bring nearly more than $30 billion in new federal money during that time. It would extend coverage to an estimated 650,000 additional low-income Georgians.

It also didn’t make sense for Georgia to build its own exchange, Deal has said, because the federal government didn’t offer states enough flexibility to create an exchange that would be unique to Georgia’s needs.

The failures of the federal insurance marketplace simply underscore the belief of many that the government has no business getting involved in an industry that should be left up to the free market, said Georgia state Sen. Judson Hill, R-Marietta.

“Obamacare comes with a price tag that Georgians cannot afford to pay,” Hill added.

‘Learn from the successes and failures’

Still, discouraged Obamacare supporters in Georgia point to Kentucky as proof the Affordable Care Act can work when — and if — HealthCare.gov finally begins to run as it’s supposed to.

As many as 900,000 Georgians are expected to shop for coverage on the federal site. Nearly three-fourths of them could possibly qualify for federal tax credits to make premiums more affordable.

Sixteen states in all created state-run insurance exchanges, not all of them as successful as Kentucky. The states that are performing well, however, show there’s demand and a need for health coverage under the law, said Tim Sweeney, a health care expert with the Georgia Budget & Policy Institute.

“We can’t go back and make any decision differently, but what we can do is learn from the successes and failures where they’ve occurred and build on that to (achieve) success going forward,” Sweeney said.

Even some red states with Republican governors, such as Idaho, decided if they had to comply with the law that they could do a better job than the federal government, he said.

“States that sort of stuck their necks out to do more … and in states where it didn’t fit conventional wisdom … it might look to be a good decision now,” Sweeney said.