John Lewis: rooted deep in Alabama soil

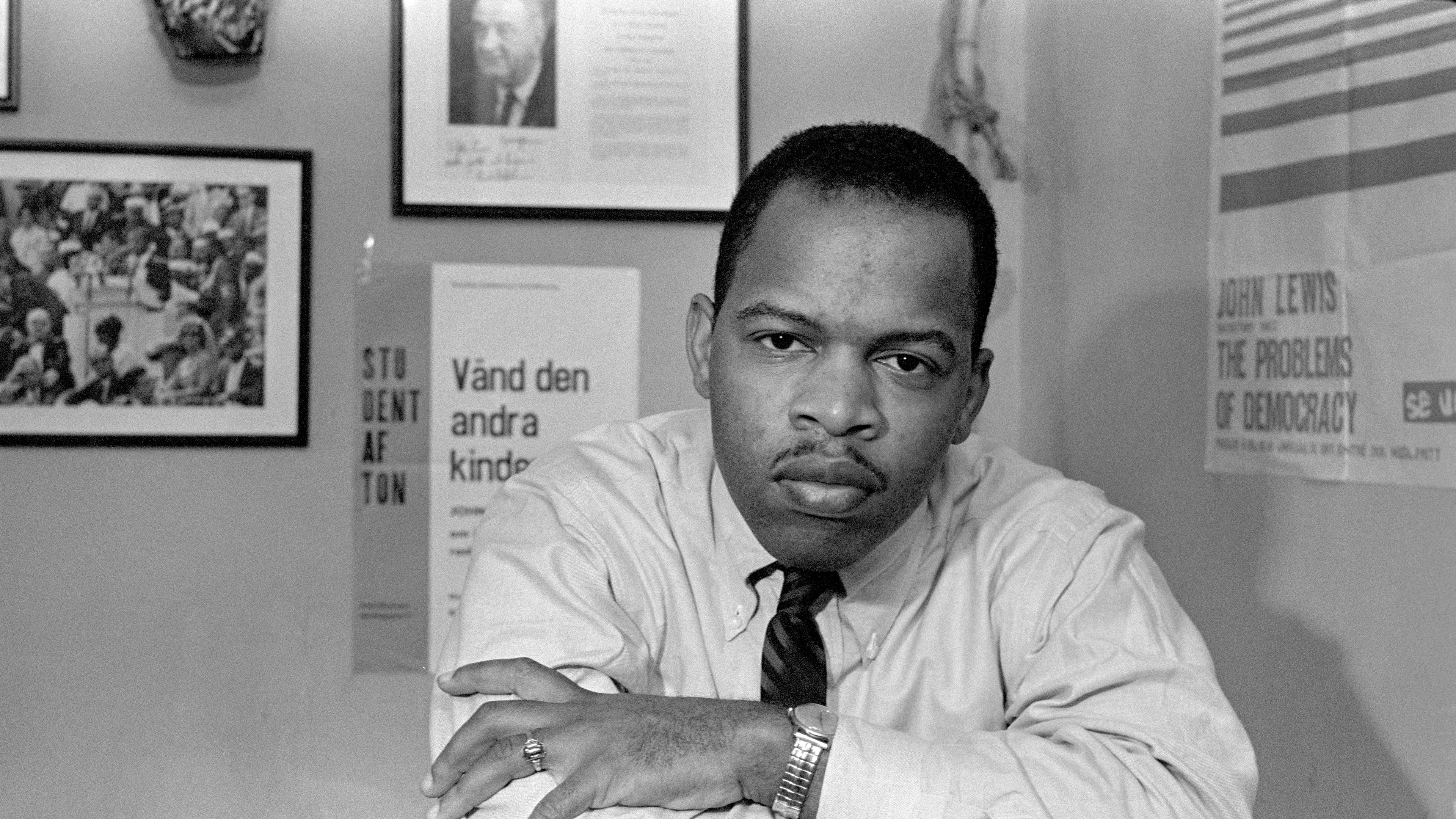

“So you are John Lewis? The boy from Troy,” Martin Luther King Jr. said upon meeting the teenager who would become one of the civil rights movement’s most famous, vocal and long-lived members.

It was 1958 and Lewis, only 18, raw, young, impassioned and feeling called to do something for the movement, had just walked down the paneled stairs of First Baptist Church in Montgomery, to find the rising leader sitting with the church’s pastor, the Rev. Ralph David Abernathy.

King had invited him after receiving a letter from Lewis asking for his help to integrate an Alabama college. The 145-pound Lewis had spent the entire 51-mile bus ride rehearsing what he was going to say at the meeting that proved to be a key step in launching him on the path of non-violent resistance and activism that put him on a national and international stage.

The public grew to know Lewis as the seemingly implacable and fearless marcher and freedom rider, who never punched back physically though beaten with cops’ billy clubs and Klansmens’ fists. It knew him as the arrested demonstrator and the 23-year-old speaker at the March on Washington calling on a president to enact strong civil rights legislation or else.

More recently they’ve seen the fiery congressman denouncing President Donald Trump.

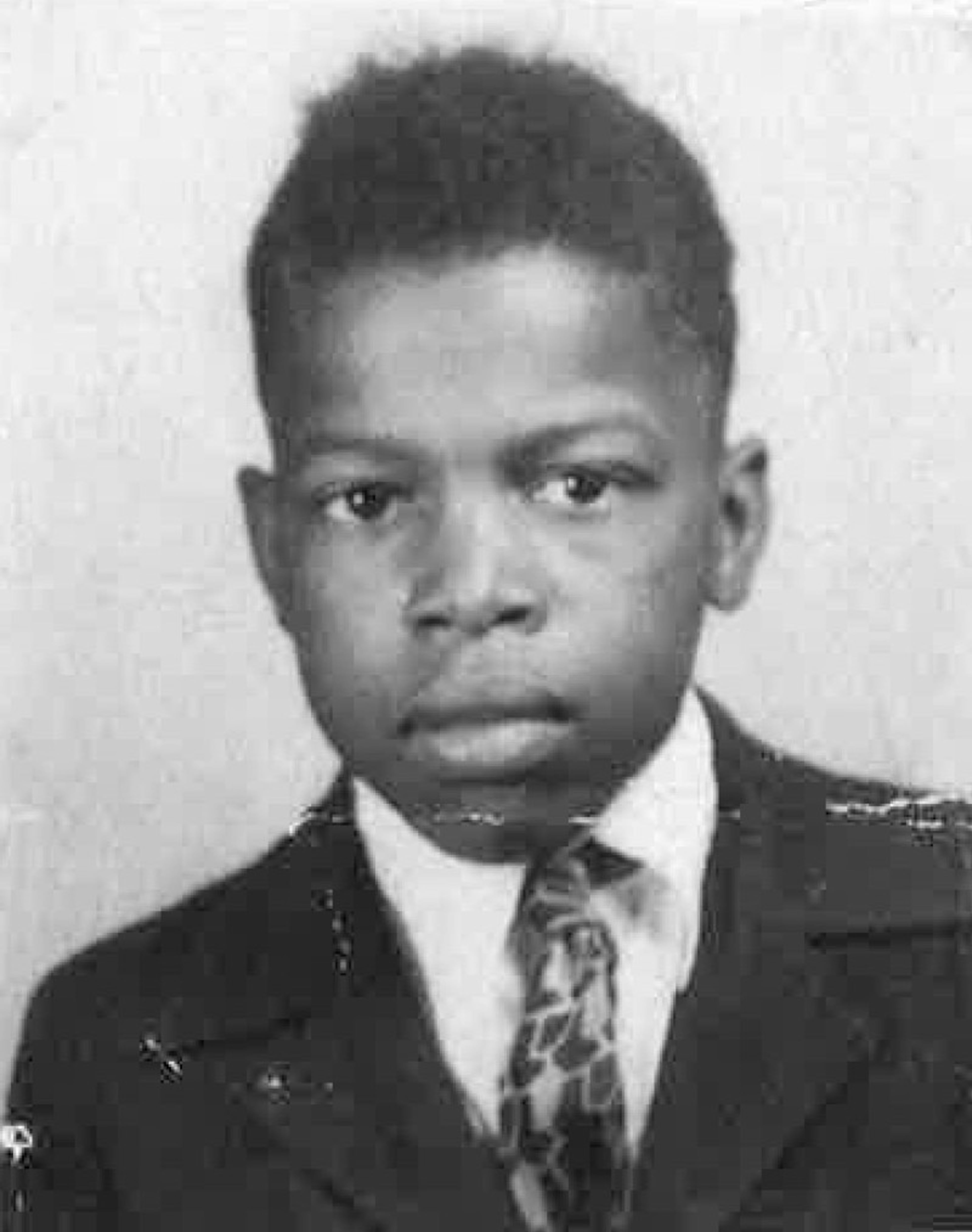

But to see who Lewis is, you must start on the family farm near Troy, Alabama, where he spent his childhood preaching to the chickens he cared for, talking his way out of picking cotton, and dreaming of a life beyond overheated Alabama fields and Jim Crow laws.

His family says through it all, John Robert Lewis is the same man he learned to be under the rural tutelage of his parents. The same tender heart that caused him to refuse to talk to his parents after they would kill one of his chickens for Sunday dinner. The same dreamer who ran away from fieldwork to attend school. The same man who, while refusing to shed a tear when he endured insults and blows, became a doting father and uncle unashamed to cry in public over joy.

The same man called John by the public was known to the family as Robert — almost a different person.

He was and is a Lewis, but obeyed a call he heard that took him away for different purposes in life — a purpose his mother accepted, though she discouraged her other children from joining.

He was a teenager by the time his baby sister, Rosa Tyner, was born. And as she got older, she asked their mother about the brother whose arrests sometime unfolded on their black and white television.

“She told me that there

were a lot of wrongs going on in the world, and Robert was trying to help right the wrongs,” Tyner said.

.

Growing a Future

Today, fewer than 20,000 people live in Troy, about 200 miles southwest of Atlanta and 830 miles from Washington D.C. Pike County, boasted 33,114 people in 2019, just 614 more people than were in the county when Lewis was born in 1940.

In 1861, just before the Civil War and 79 years before Lewis was born, as many as 2,000 slaves toiled on Pike County’s red clay soil and rolling fields.

The Lewis family’s mailing address may be “Troy,” but they are about eight miles from downtown and proudly admit they live in the “country” on the same land their father purchased 76 years ago.

About a mile away from the Lewis farm is a reminder that the past is not a time but a mindset. Catty-corner to one of the many churches that dot the views, a ramshackle house has a giant Confederate flag for a front room curtain.

The first thing you notice when you drive into Tyner’s driveway is the large animal pen. Inside, three cows and a white horse lay side-by-side under a shade tree to hide from the 103-degree July heat.

Tyner, 66, who returned to Troy in 2012 after 35 years of living in Northern California and working as a longshoreman, notes that those cows and horse belong to her brother, Samuel.

“My cows are down there,” she said, pointing to a distant pasture behind a sea of trees.

Look in every direction, and everything thing you can see belongs to the Lewis family.

By 1944, Eddie Lewis, their sharecropping father, had worked hard enough to save $300 and purchase 110 acres from a white grocer. They moved into a three-room shack on the land with no heat or running water and lived in it 10 years before Eddie built a new home on the land. That house was torn down in 1996 to make way for a newer one, that Tyner lives in.

Her brother Henry Lewis lives in a big brick house across the road, next door to brother Samuel Lewis. Their brother Freddie’s daughter and her family are in the next house over. All part of the Lewis farm.

On those 110 acres, Eddie Lewis became his own boss, planting cotton, corn, peanuts, beans, and vegetables, which he sold, and used to feed his family. They also raised chickens, cows, and hogs.

“We had six mules, two horses and a tractor,” Henry Lewis, said. “And they would all be in the field at the same time.”

Standing in his yard, Henry Lewis, the youngest boy in the family at 67, says their father taught them early about working to make the future better. He bought and tended this land, not for his own enjoyment, but to leave something behind for his children and grandchildren.

“He would plant a tree – a grapevine or something like that – and then he’d make the statement: ‘This grapevine will not do me any good. But it will for you,’” Henry Lewis remembered. “‘You and your kids will enjoy a lot of grapes off this vine.‘”

Called Beyond the Fields

Eddie and Willie Mae Lewis, called “Mul” by family, had 10 children spread across 19 years.

Ora. Edward. John. Adolph. William. Ethel. Freddie. Samuel. Henry. Rosa.

Ora, Edward and Adolph died before John.

Growing up, the 10 children worked the farm themselves. John Lewis loved tending the chickens but hated fieldwork.

In his autobiography, Lewis spends considerable time detailing how he cared for the family’s chickens, which he considered his own. The boy John Lewis, who wanted to be a minister, would preach to them, baptize them, bury them, collect their eggs, and get mad at his parents when they made one a meal. He would remain obsessed with those chickens all his life.

“Whenever I call he would ask, ‘How are the chickens? How many eggs did you get?’” said Tyner, admiring the chickens that she now tends to in a coop directly behind her house. “I would say, ‘I didn’t call you for you to ask about the chickens. You didn’t even ask how I was doing.’ Every time he would come home, he would come out here and see the chickens.”

When it was time to harvest the crops, Eddie would pull the kids out of school to get the work done. Nobody complained, except Lewis.

“He would say this ain’t nothing but slavery out here in this hot sun,” Tyner said. “He would get on my mother’s nerves so bad. He was more trouble than he is good.”

Lewis wanted to go to school. So he would hide under the house until the school bus came then run after it.

Eddie would chase Lewis yelling for him to come back before he vanished onto the yellow bus.

Adolph, a giant of a man built like John Henry — the folkloric African American steel driver — would watch his older brother run to the bus. Watch him run to his potential.

“Let him go Daddy. I’ll do his work,” Adolph would say.

“Adolph did enough work for two or three men,” Tyner said.

“[John] didn’t like the labor part of the farm work. The rest of us were fine with it,” Henry Lewis said. “He felt there was a higher calling for him. He thought there was more out there in the world and he wanted to explore it, and he did.”

Fear and shame

Ministering to the chickens had set him on a path to become a Baptist preacher. Like many do today, but few did in 1957, Lewis left Troy for good at 17 when he moved to Nashville to attend the American Baptist Theological Seminary. He joined the civil rights movement in Nashville, first as a member of the Nashville Student Movement, then as one of the original Freedom Riders, who put their lives on the line testing a then-new Supreme Court ruling desegregating public buses.

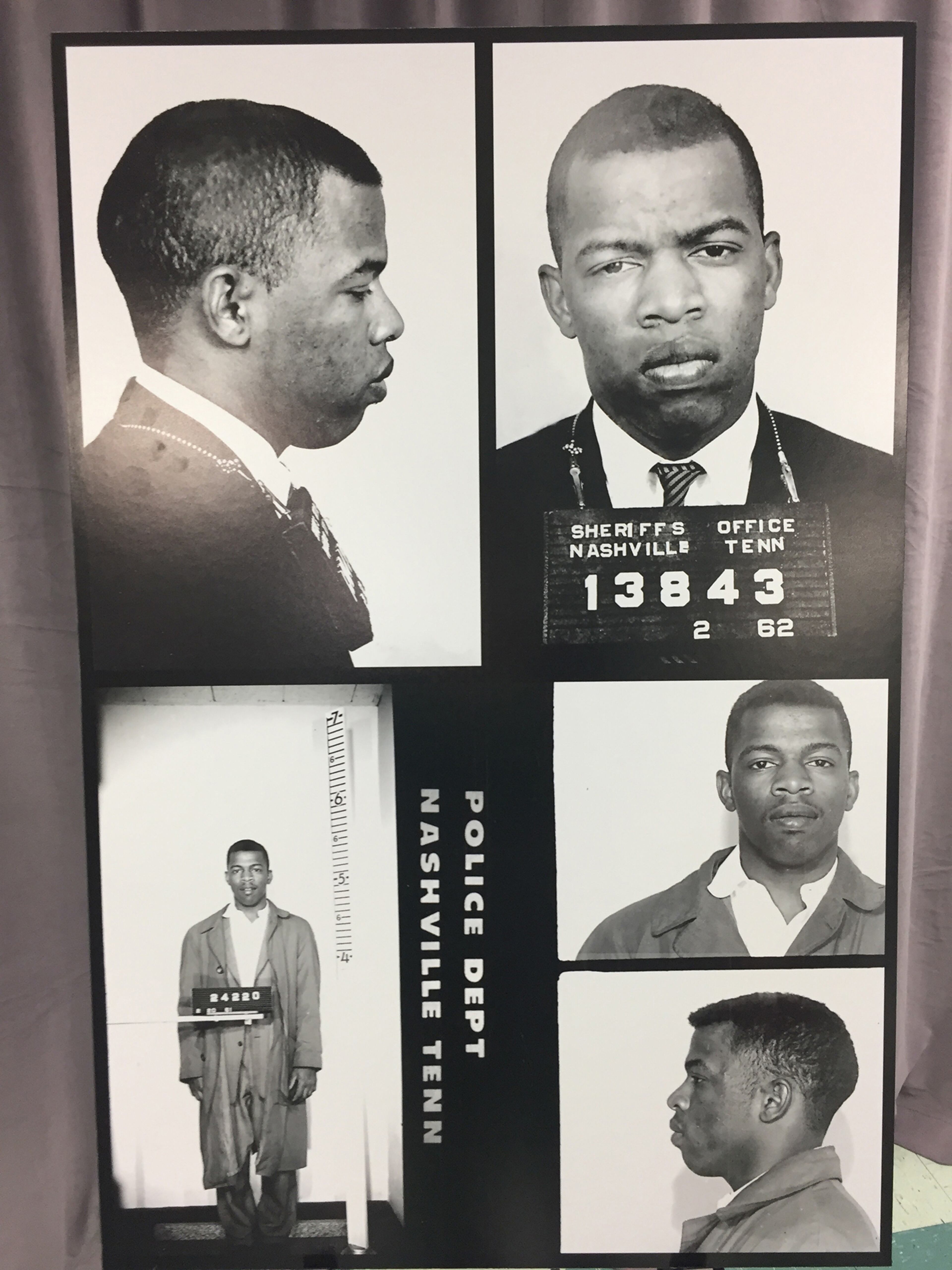

He grew into the movement. In 1963, as chairman of the Student Nonviolent Coordinating Committee, he was the youngest speaker at the March on Washington. Over years of demonstrations, he would get arrested more than 40 times and face what he said was near death from the beatings and attacks he personally suffered from the Ku Klux Klan and the police.

Back home in Troy, his parents and nine siblings watched. In his autobiography, Lewis wrote that he feared his many arrests would bring shame to his family and that there was a temporary rift with them early in his career.

Tyner said her family was never ashamed of Lewis, remembering how proudly Eddie would sit up in his easy chair every time he saw Lewis on television.

“We would watch him, and at first I didn’t comprehend it. They showed one time they were taking him to jail and I was like, ‘What did he do?” Tyner said. “There were just so many of them getting arrested, but once I talked to my mother and began to understand what the sit-ins were, I knew.”

Tyner, was only seven years old in 1961 when Lewis was sent to the notorious Parchman Penitentiary in Mississippi on a charge of disorderly conduct, for using a “whites only” bathroom in Jackson.

But how could they be ashamed of him? He was the first Lewis to leave. The first to go to college. First to make a difference in the world.

Henry Lewis, who was 11 years old when Lewis spoke at the March on Washington, lists his big brother as his hero.

“He’s done so much good for the human race,” he said. “And even with all the accolades and all this stuff, it didn’t change him from being who he really is. He was that humble guy years ago; he is still that humble guy.”

Sitting in the family room of her house with Samuel, both wearing masks to protect themselves from the coronavirus, Tyner asks her brother: “Can you imagine a person getting beaten, knocked down in the head, arrested so many times and just doing this constantly, with people being so mean and hateful?”

“He did that. He should be everybody’s hero.”

Even so, they were scared for John and themselves.

Set Apart

“We knew they were in harm’s way,” Henry Lewis said of those in the movement. “And we knew that the chances of him getting seriously injured or killed was a real possibility.”

That doesn’t take into consideration the possibility of retaliation on the family.

Martin Luther King’s family lived in the middle of Atlanta. Lewis’ family lived on a secluded farm in rural Alabama. When Lewis first visited King, he wanted to talk to the great man about getting help to integrate Troy State University. One of the reasons Lewis dropped his effort was that his family feared they could somehow lose their 110 acres.

“Daddy didn’t say much. It was more my mother,” Tyner said.

“You could always hear her praying for John’s safety. A lot of times the two of us end up in the kitchen together. She would be making biscuits and praying the whole time. She was a strong Black woman.”

Strong enough to keep her remaining children out of the movement.

“Our parents would not have let us, because they already had one child in it,” Tyner said. “They believed in what he was doing, but it was dangerous too. I believe that John had a calling for what he did.”

Samuel Lewis, who served in Vietnam after being drafted into the Army in July of 1968, three months after King was murdered, said he could not have done what his brother did.

“I can take more now than I could have done then,” Samuel Lewis said. “But I got that from following him. I learned to be calm from him.”

Tyner agreed.

“I am very proud and honored to be his little sister with the sacrifices he has made,” Tyner said. “I believe that he was chosen to do what he did. Ora couldn’t have done it. Edward, Adolph. It wasn’t in us.”

Back to Troy

But as John Lewis’ prominence increased and he began to collect accolades, work often kept him away from his immediate family, including wife, Lillian, who died in 2012, and son, John-Miles, who the couple adopted as a baby in 1976. John-Miles remained at his father’s side during his final weeks in Atlanta.

He keeps a low profile. He spoke about being raised by a civil rights leader in a 2004 interview with the Washington Post.

“He always tried to instill in me what the past really meant and how much the past affects now,” he said.

Lewis included his family in his life as much as he could, often sending his siblings invitations to events where they rubbed elbows with political titans. He gave Tyner her first plane ride and bought her her first bottle of perfume, Chanel No. 5.

Henry Lewis counts meeting five presidents. He was in Washington the day his brother was sworn into Congress in 1987, and he was also there in 2011 when President Barack Obama placed a Presidential Medal of Freedom around John Lewis’ neck. Henry Lewis talked to his brother on the phone at least three times a week. Henry asked about Washington, and Lewis asked about things back home. Henry Lewis always called his brother “Congressman’ Out of respect.

Lewis made it back to Troy typically on Thanksgiving and Christmas. Tyner said Lewis had been in the city too long to still have country ways.

Even when Willie Mae, who died in 2003, was living in the house by herself, Lewis would still stay in a Troy hotel when he visited.

“Mul would say ‘Let him go on. He’s used to people picking up behind him and making his bed, I am not gonna do that,‘” Tyner said. “But he enjoys when he comes here and hates to leave. He always talking about, “Imma retire and build me a house down here. Imma do this, Imma do that. I said ‘You not gonna retire. Where you gonna live at?’”

Samuel Lewis said his brother’s leaving home and the work he did changed the course of their lives back in rural Alabama.

“If he hadn’t done what he done, we might still be on the farm. We farm now as somewhat of a hobby.”

Uncle Robert

Rosalynn Tyner King, Tyner’s youngest daughter, said Lewis always tried to connect with the next generation of Lewises. He had about 30 nieces and nephews.

He came to their college graduations, hosted them in Washington and on trips like the Essence Festival for book signing.

“I grew up learning and watching him in documentaries like “Eyes on the Prize,” said King. “I would see him in pictures and stick my chest out and say that is my uncle. I was always proud and aware of the sacrifices he made. And all of the accolades didn’t change him as a person, and I think that speaks volumes.”

But to her, he is still just family.

“I can call him on the phone and joke with him. We tease him, like when we got to be taller than him,” King said. “He has a little stomach, and he loves my mom’s cooking, so he would always come down to eat then nod off on the couch. We would take pictures of him. But he was always Uncle Robert.”

At King’s graduation from the University of Chicago, the family remembers how he cried when she got her degree.

“Why you crying?” King asked him.

“I was thinking about Mul. If she could see you right now she would be so proud,” Lewis answered..

“Mul see me, but you can’t be crying. People think a lot of you as a congressman, you can’t be crying,” King told him.

“He could drop a tear. Always,” Tyner said. “He was just always emotional. I would look at him and say don’t start.”

A chance to say goodbye

When John Lewis moved back to Atlanta this summer, his family would make the three-hour pilgrimage from Troy every weekend to be by his side. Henry Lewis would rub his hands asking, “Congressman, are you okay?”

Lewis told his family more than once, “I’m at peace, I’m ready.”

Tyner said, “I am a realist. I know that everybody has to die.”

“When I saw that he was so sick, I said ‘Lord, all that he has sacrificed.’ I prayed and said ‘don’t let him go like this.’ I asked Him to heal him. Then one day I thought about it. He has given so much to the world and he just might be tired.”

“He’s at peace,” she said. “So, if John is ready for it, I can give him up.”