No immunity this time for former Georgia deputies in 2017 Taser death

A judge, in an about-face, has denied immunity to three former Washington County deputies facing murder charges in the Taser death of an unarmed Black man with schizophrenia.

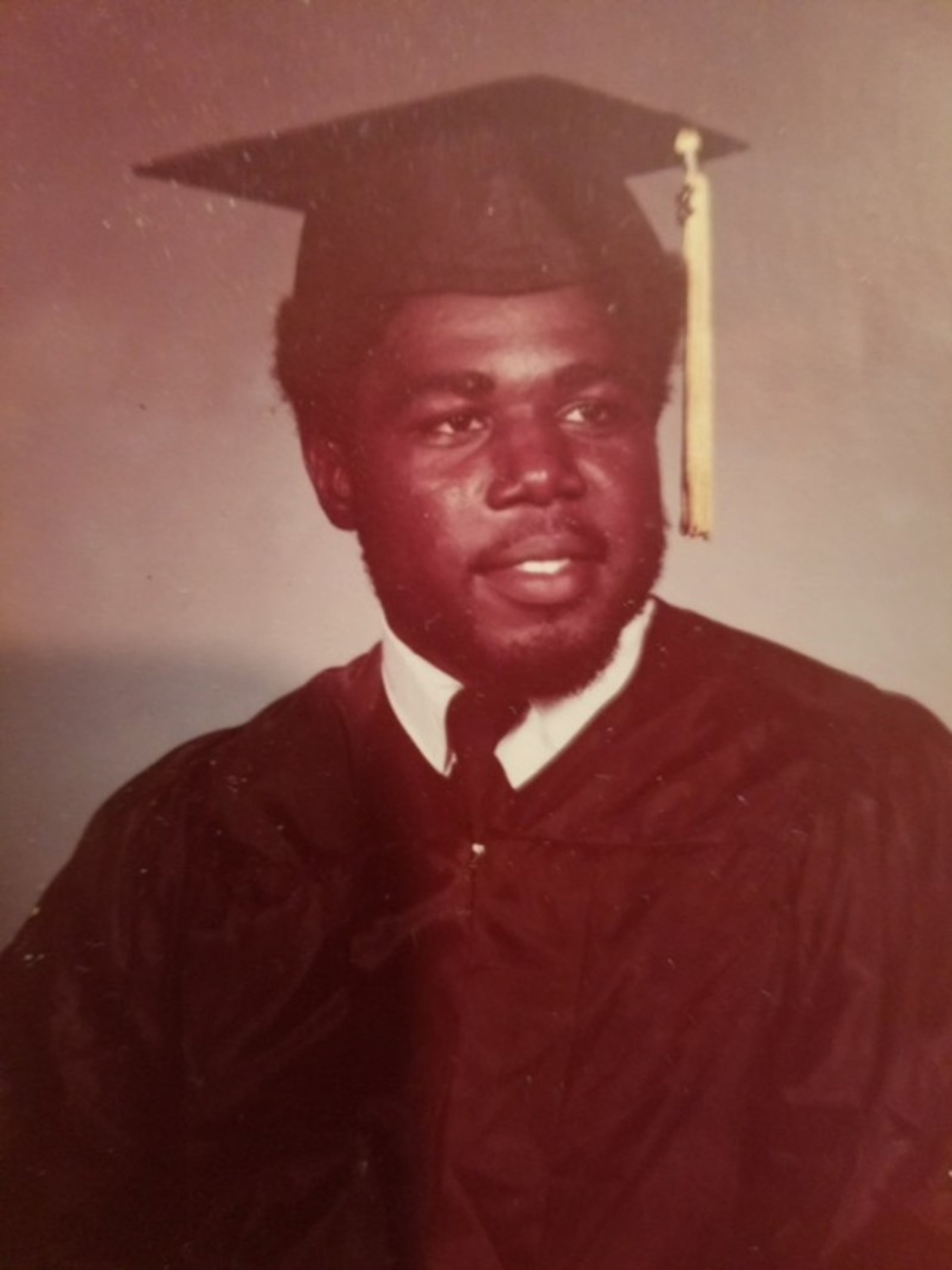

Eurie Martin, 58, died after being stunned repeatedly with Tasers by then-deputies Henry Lee Copeland, Michael Howell and Rhett Scott, all of whom are white. Unless they appeal, the defendants are expected to stand trial sometime next year.

A year ago, Senior Judge H. Gibbs Flanders granted the three defendants immunity from prosecution. But in November, the state Supreme Court unanimously overturned that decision, saying Flanders had misapplied the law and instructing him to try again.

On Tuesday, in a 23-page ruling, Flanders reversed course.

“We’re looking forward to having a trial date being set so that a jury can make a determination as to the responsibility of the persons involved,” District Attorney Hayward Altman said. “That’s what I’ve wanted from Day One.”

Pierce Blitch, a lead attorney for the ex-deputies, did not respond to requests for comment.

On July 7, 2017, with the heat index topping 100 degrees, Martin was walking 25 miles from his group home in Milledgeville to visit relatives in Sandersville. When he stopped to ask a homeowner for a drink of water, the homeowner refused and called 911.

Howell arrived on the scene first, soon followed by Copeland and a bit later by Scott. By the time the incident was over, Scott had activated his Taser five times, Copeland had employed his Taser three times, and Howell — using Scott’s Taser — had activated it three times, the ruling said.

When EMTs arrived, Martin had no pulse and was not breathing. He was pronounced dead at the scene.

Upon encountering Martin, deputies Howell and Copeland ordered him to stop walking on the roadway, place his hands above his head and get on the ground.

But they should not have done that, because the deputies had no reasonable suspicion that Martin had committed the offenses of loitering or walking on a highway, Flanders said.

And because of that, Martin was justified in refusing to heed the officers’ demands and resisting their attempts to arrest him, the order said.

Moreover, when Howell and Copeland initially applied their Tasers on Martin, Martin was not the physical aggressor, Flanders said. The deputies were the aggressors and for that reason they cannot be immune from prosecution, the order said.

Scott’s position is different because when he arrived, Howell told him that Martin had been fighting and resisting arrest. This gave Scott reasonable suspicion that Martin had committed the offense of obstruction, and it meant Scott could lawfully try to detain Martin at the scene, the judge said.

The dashboard camera in Scott’s patrol car showed that Martin was still refusing to get on the ground. It also showed that Martin was facing the officers with his hands on his hips.

Yet within 24 seconds after he got out of the car, Scott discharged his Taser on Martin. This was not a reasonable use of force because there was no evidence that Martin’s conduct could be construed as an imminent threat, Flanders wrote.

Even if there was such evidence, Martin was unarmed and it was improbable that he was going to escape, Flanders wrote. “The three officers, including Deputy Scott, did not make use of their most valuable resource, time, before resorting to use their Tasers.”