“The State Board of Pardons and Paroles has reviewed and considered all of the facts and circumstances of the offender and her offense, as well as supplemental information presented to the Board. … It is hereby ordered that Ms. Gissendaner’s renewed request for reconsideration is denied and the previous decision of the Board issued on the 25th of February 2015 stands.”

— Parole board’s public explanation of decision denying clemency to Kelly Gissendaner

“…A written decision relating to a pardon for a serious offense or commutation of a death sentence shall … include the board’s findings which reflect the board’s consideration of the evidence offered that supports the board’s decision. …”

— HB 71, enacted 2015

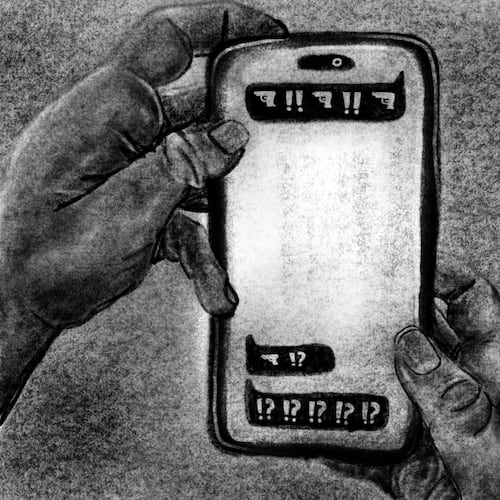

Hours away from execution, the condemned inmate’s last hope lay in an official grant of mercy.

The inmate was guilty of murder but hadn’t carried out the killing. Surely, the inmate’s supporters thought, that would resonate with the Georgia Board of Pardons and Paroles. It alone had the authority to approve clemency — to turn a death sentence into life.

This scenario has played out twice in the past 14 months, with sharply different results. Last year, the parole board granted clemency to Tommy Lee Waldrip of Dawson County. This week, it denied Kelly Gissendaner, who was executed early Wednesday.

As it did in Waldrip’s case, the board left its decision on Gissendaner unexplained. This time, however, its reticence may conflict with a new state law mandating more transparency in the clemency process.

Under the new law, enacted partly in response to Waldrip's clemency, the board is supposed to issue findings "which reflect the board's consideration of the evidence offered that supports the board's decision."

But in a press release and another document released Wednesday, the board said only that it “reviewed and considered all of the facts and circumstances of the offender and her offense, as well as supplemental information presented to the board.”

The law could be interpreted to apply only in cases in which the board grants inmates’ requests, lawyers said. Others said no such distinction exists.

“My thought is they need to explain why they do and why they don’t” grant clemency, said Dawson County Sheriff Billy Carlisle, who last year strongly criticized the Waldrip decision. “Her family needs to understand why. I’m not saying it’s right or wrong to deny it. To me, there’s no consistency in any of it. That’s what’s so frustrating.”

A spokesman for the parole board did not comment Wednesday.

Gissendaner, 47, exhausted her appeals to the parole board and several courts in the hours before she was put to death by lethal injection. She was convicted of conspiring to kill her husband, Douglas Gissendaner, in 1997 in Gwinnett County. Her lover, who admitted killing Douglas Gissendaner, will be eligible for parole in seven years. Kelly Gissendaner’s supporters pointed to the sentencing disparity and to her religious conversion as reasons to spare her life.

The board’s five members heard arguments for and against Gissendaner behind closed doors Tuesday. Their deliberations, if any, were private — as were their votes. Unlike appointees to other state boards and commissions, members of the parole board keep no public record of individual votes; officially, that information is a state secret.

“Georgia’s parole board operates under a cloak of secrecy,” said Sara Totonchi, executive director of the Southern Center for Human Rights, which represents death row inmates.

Gissendaner and other recently executed inmates “had compelling reasons for clemency to be granted, yet they were denied,” Totonchi said. “Georgians deserve to know the reasons when the board denies mercy.”

Georgia is one of five states in which independent boards decide clemency cases; the governor has no say. In the other states, according to the National Association of Criminal Defense Lawyers, decisions follow public hearings.

The Georgia board is one of the nation's most secretive, The Atlanta Journal-Constitution reported last year. Thirty-seven states allow varying levels of public scrutiny in decisions on pardons, parole and commutations of death sentences. Georgia's board, however, conducts only administrative business in public. It answers to neither legislators nor the governor.

The board has spared nine death row inmates since the 1970s, according to the Death Penalty Information Center. It explained none of the decisions. But records show the board heard arguments that four of the nine had received harsher sentences than co-defendants. In two cases, prosecutors and jurors said the death penalty would not have been imposed if a sentence of life with no parole had been available. Two inmates cited religious conversion. And one was a juvenile suffering from mental illness when he committed murder.

Why the board thought those nine deserved mercy and others didn’t remains a mystery.

Waldrip, his son and a brother all were convicted in the 1991 murder of Keith Evans, who was scheduled to testify against Waldrip’s son in an armed-robbery case. In separate trials, only Tommy Waldrip received the death penalty; the other two defendants, one of whom shot and beat Evans to death, were sentenced to life in prison.

In denying Gissendaner, the board disregarded entreaties from death penalty opponents including Pope Francis.

Carlisle, the Dawson County sheriff, still wants to know why the board commuted Waldrip’s sentence to life in prison. The board refused requests from Carlisle and from the Georgia Sheriffs Association to declassify its files.

“Once it’s over, it’s over,” Carlisle said. “It seems like they’ve forgotten about it.”

About the Author

Keep Reading

The Latest

Featured