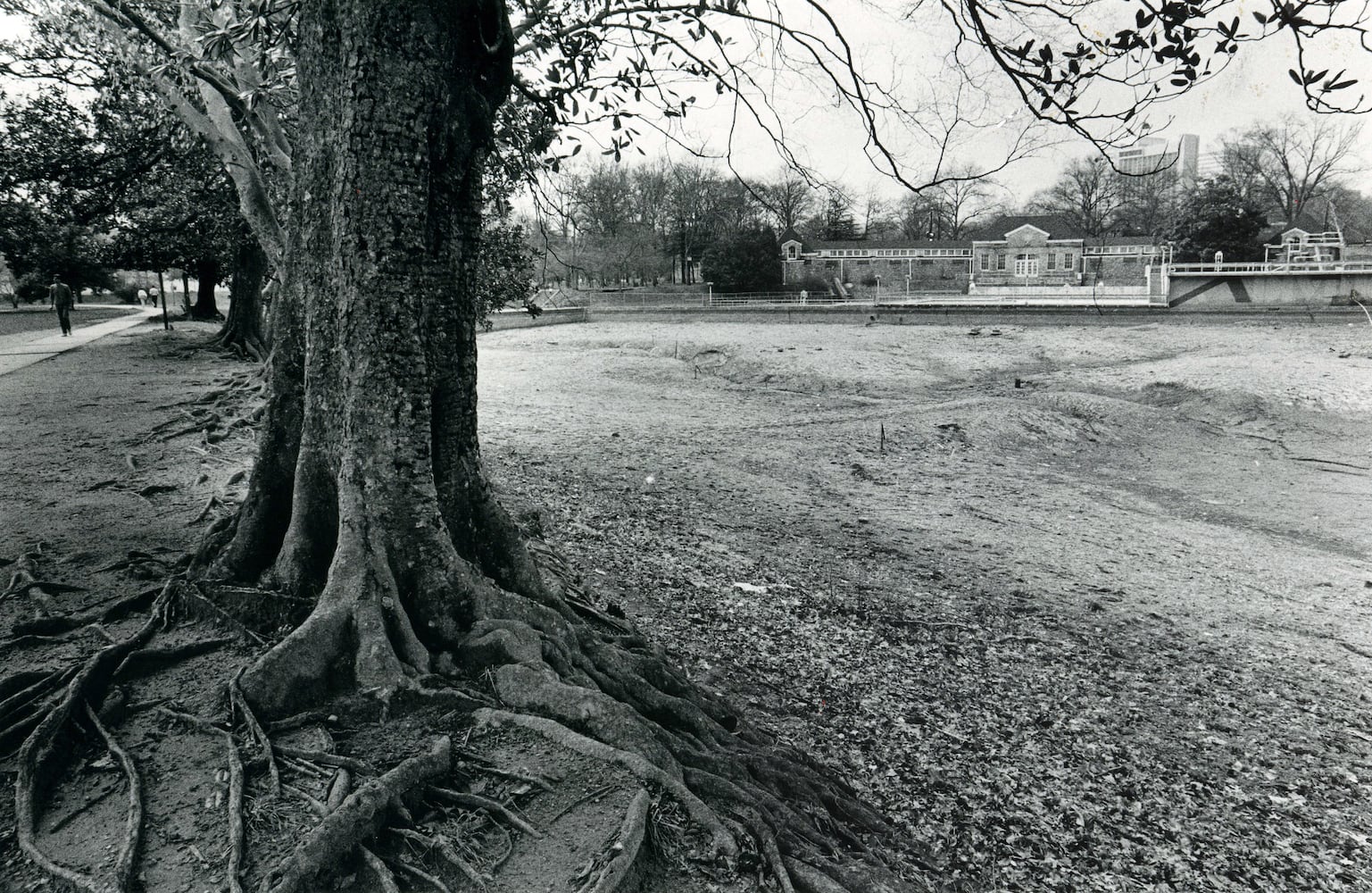

Hundreds of the old-growth trees that make up the canopy of Atlanta’s iconic Piedmont Park didn’t begin their lives in the city.

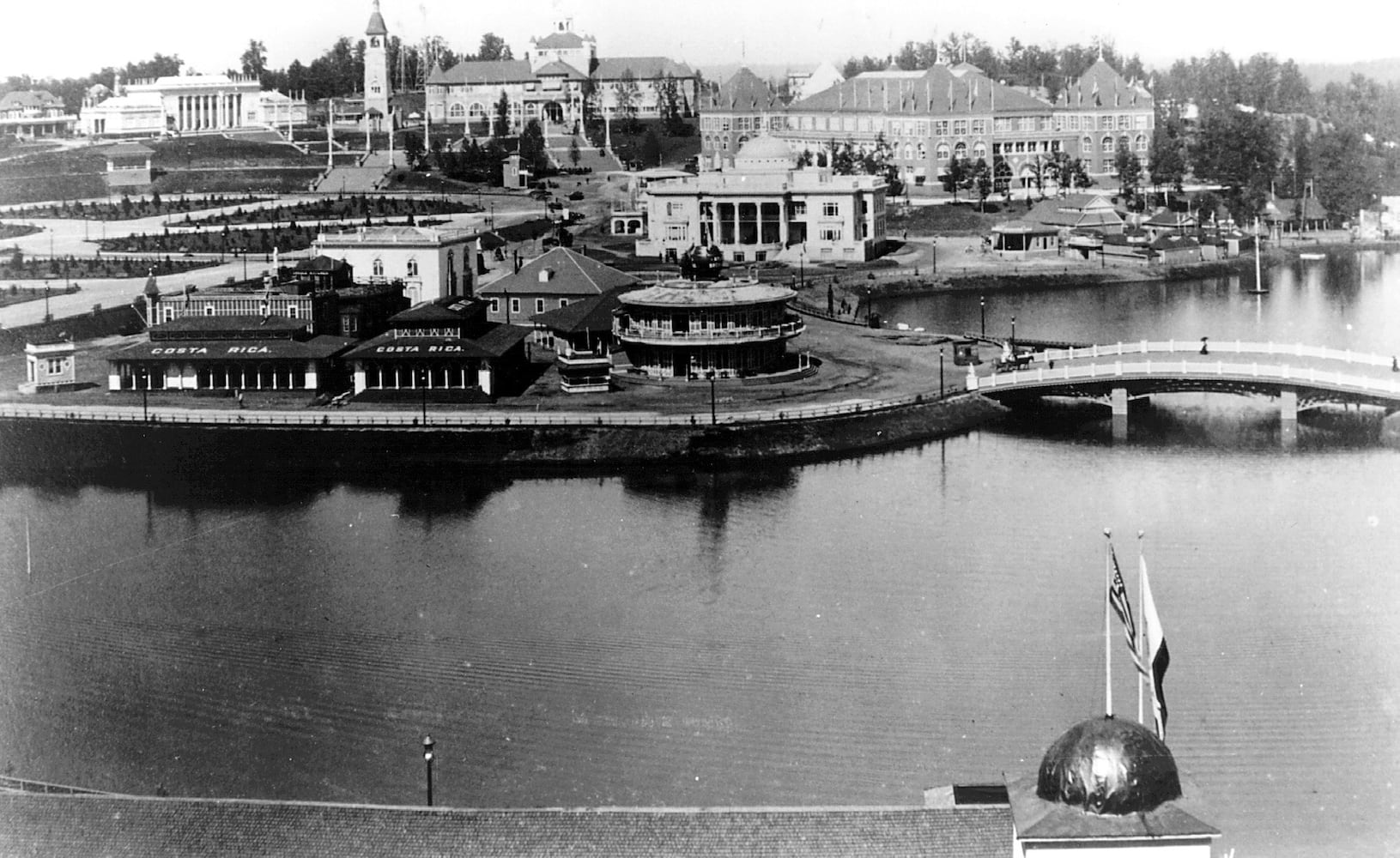

In 1895, as residents geared up to host hundreds of thousands of visitors for the Cotton States and International Exposition — Atlanta’s World’s Fair — more than 1,600 trees were imported from the famous Fruitland Nursery in Augusta.

“We don’t know what kind of trees or where exactly they were planted,” said Staci Catron, Director of the Cherokee Library for the Atlanta History Center. “But every time I am in Piedmont Park, I always wonder: ‘Is that tree from Berkmans?’”

“Some of the larger trees that remain, are they from the exposition? And the answer, some of them certainly have to be,” she said.

The city of Atlanta bought the land that is home to the 185-acre park on June 15, 1904, and extended its boundaries to incorporate it. That makes this year the 120th anniversary of arguably one of the city’s most well-known features.

But out of the park’s six million annual visitors, few are likely to notice the pieces of its history that have withstood centuries of change. The trees stand as just one example of how the park was molded by different communities.

Credit: Ziyu Julian Zhu/AJC

Credit: Ziyu Julian Zhu/AJC

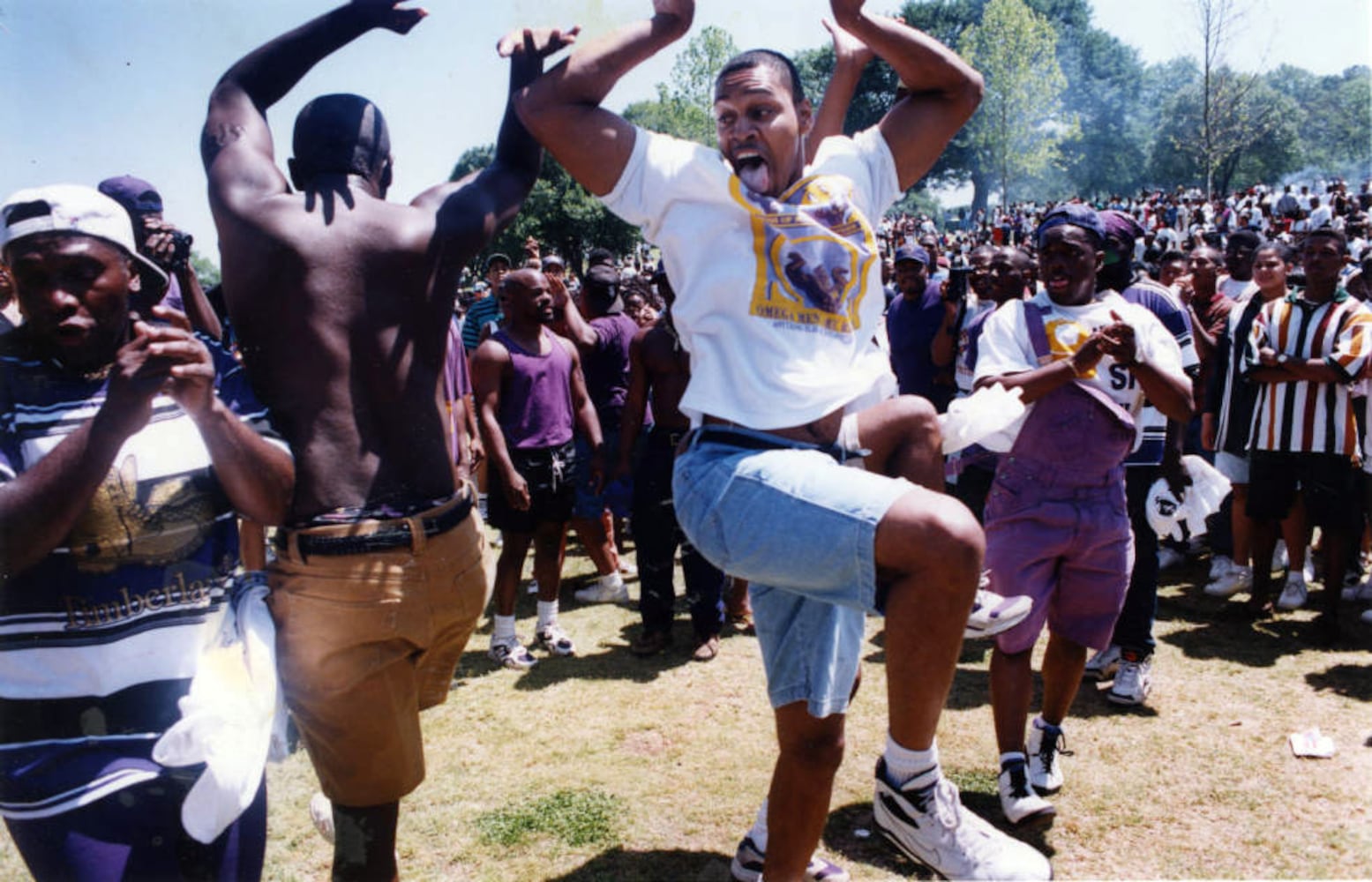

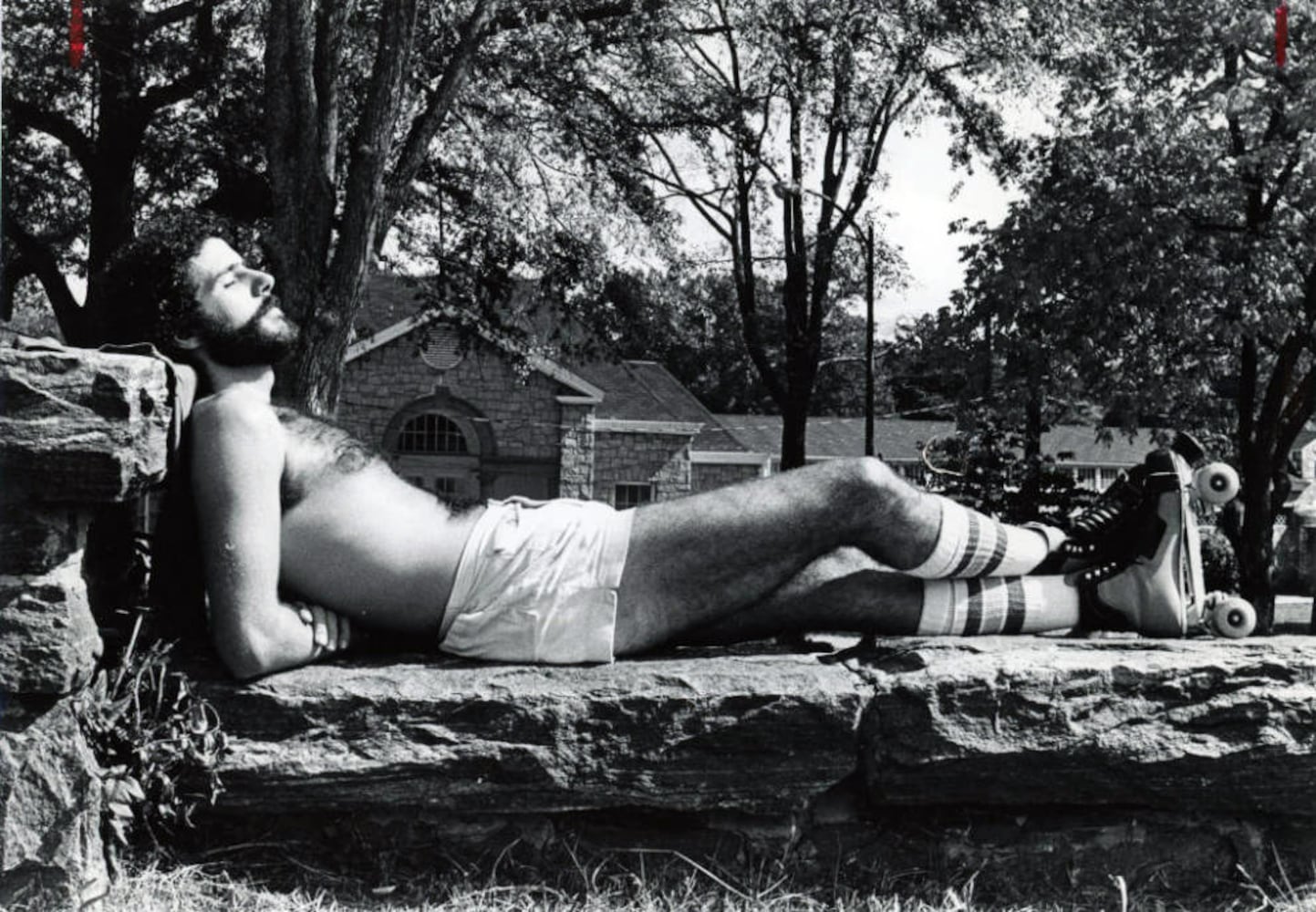

Historians say the park holds a checkered past of both exclusion and acceptance — from its original Muscogee inhabitants, followed by decades as a segregated space, to its massive festivals and its role in counterculture movements of the 1960s.

“A lot of Atlanta — if not all Atlanta — looks to it as a gathering space, a community space,” said Michael Rose, Curator of Decorative Arts and Special Collections at the history center.

“The culmination of the Pride Parade is getting to Piedmont Park,” he added. “It’s the symbol, in part, of the city coming together.”

This year, the Piedmont Park Conservancy wants those who enjoy the park to weigh in on its future.

The conservancy — established in 1989 to help fundraise for maintenance and new projects — is leading the effort to create a new comprehensive development plan. And input from Atlantans will play a vital role in the expansion, especially as the city’s population continues to grow.

“It’s amazing how much people care,” Doug Widener, chief executive officer of the conservancy, told The Atlanta Journal-Constitution. “There are a lot of different ideas, but passion and love for this park, carry through every single person and every single idea or suggestion that’s been made.”

Credit: Steve Schaefer

Credit: Steve Schaefer

Remnants of the past

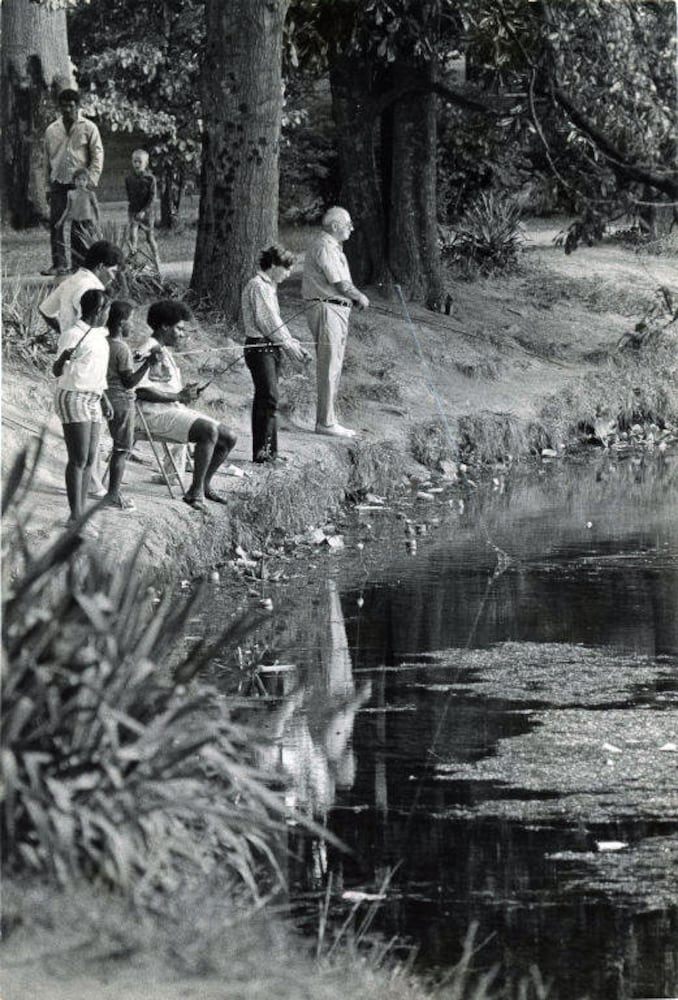

Lake Clara Meer, which reflects Atlanta’s skyline and sunsets in its waters, holds the same name as Clara Fritz, the daughter of cattle rancher John Fritz, who lived at the corner of Piedmont and 10th street.

He rented land from the original owners, Samuel and Sarah Walker, who purchased the land in 1834 for $450. The farms that operated on the land — much larger than the park today — were made up of rustic log cabins and were likely run by slave owners, experts at the history center said.

“It was considered far away from the heart of Atlanta at the time,” Catron said.

That began to change when Walker’s son sold the area to the Gentlemen’s Driving Club — an elite equestrian center that got its name from the horse and carriage buggies that carried members around the property.

The baseball fields of today were carved out of the hillside — to form a horse racetrack.

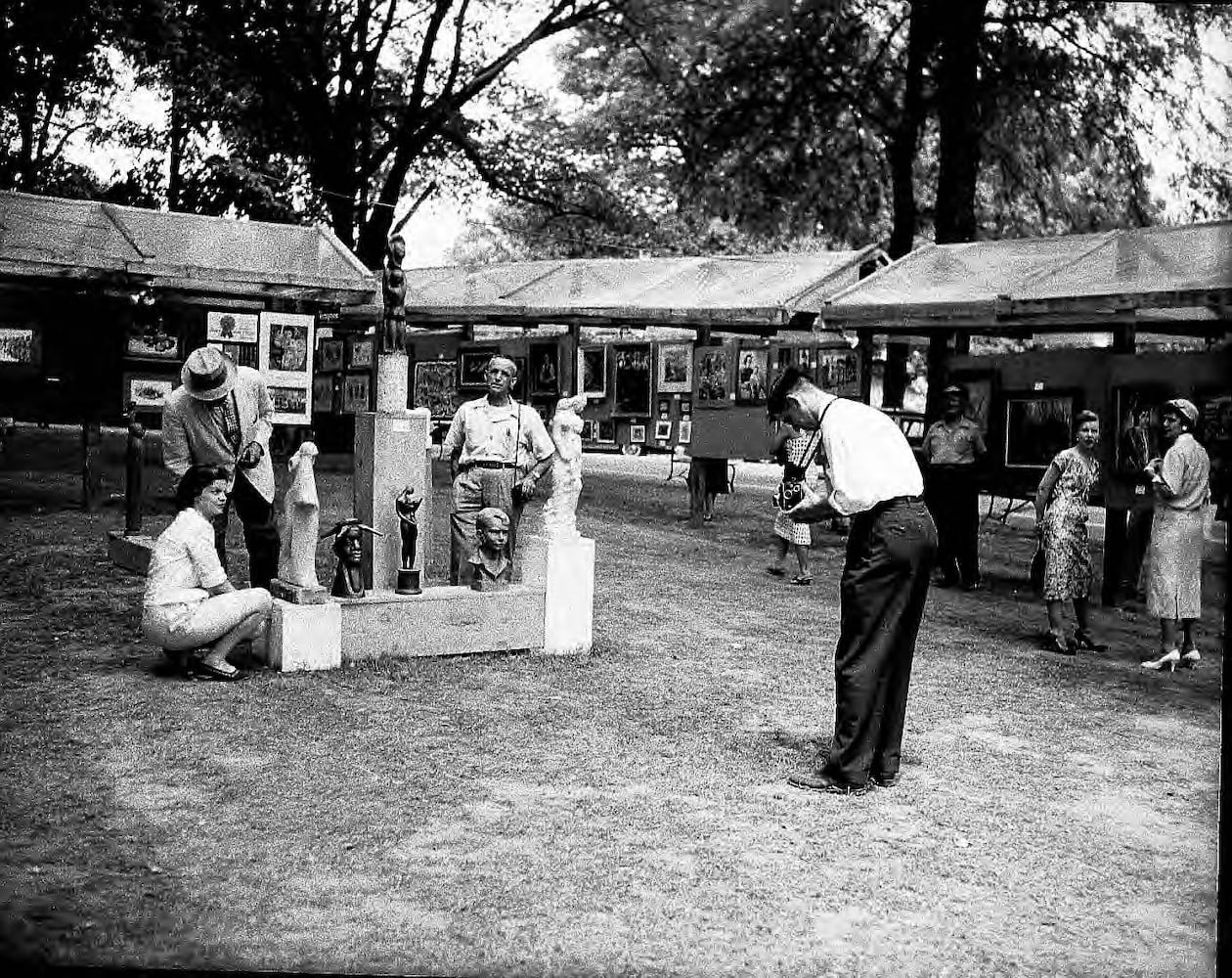

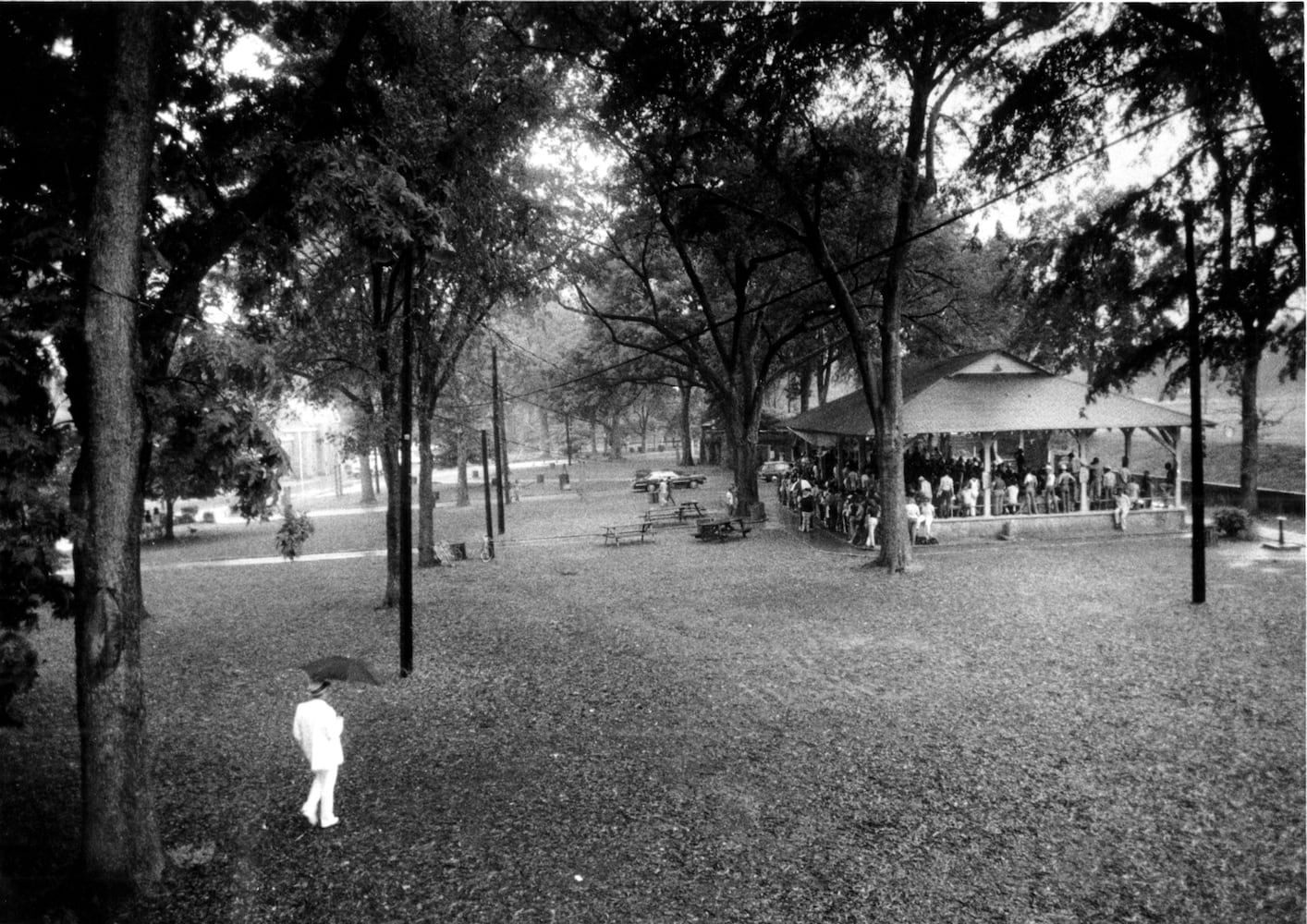

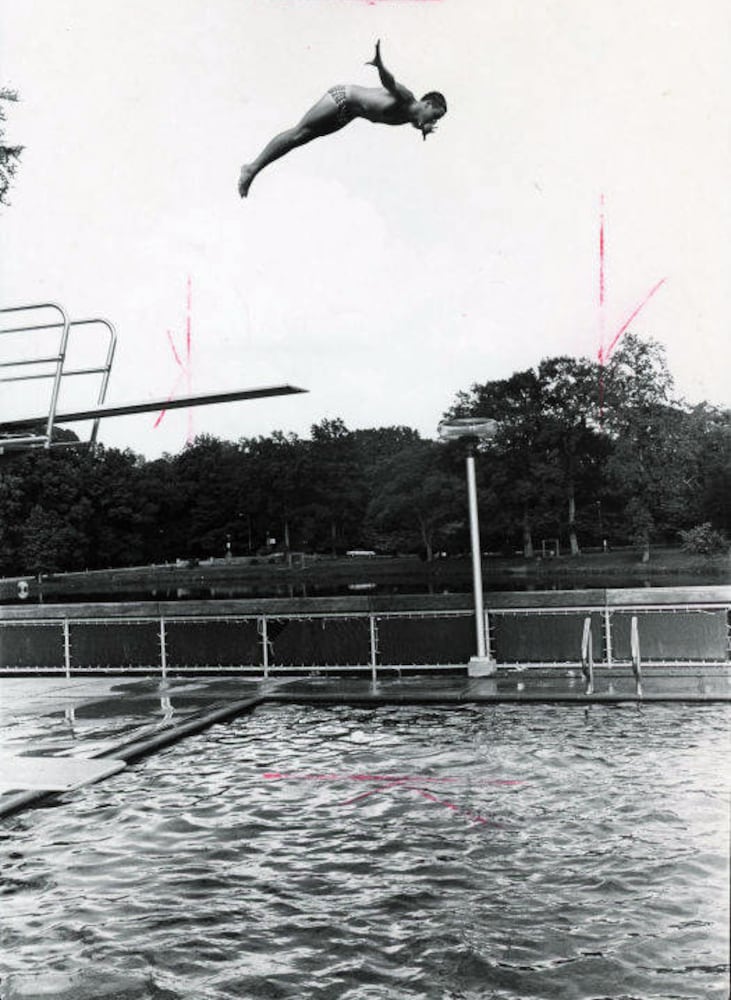

Then came years of massive festivals and expositions — giving the park a function that still holds true today with some of its largest events, like the Dogwood Festival, Atlanta Arts Festival and Atlanta Pride.

The 1895 Atlanta World’s Fair and the 1987 Piedmont Exposition put the park on the map, nationally and internationally. And they shaped the park’s landscape — hillsides were carved, fields cleared for buildings and the trees were brought in.

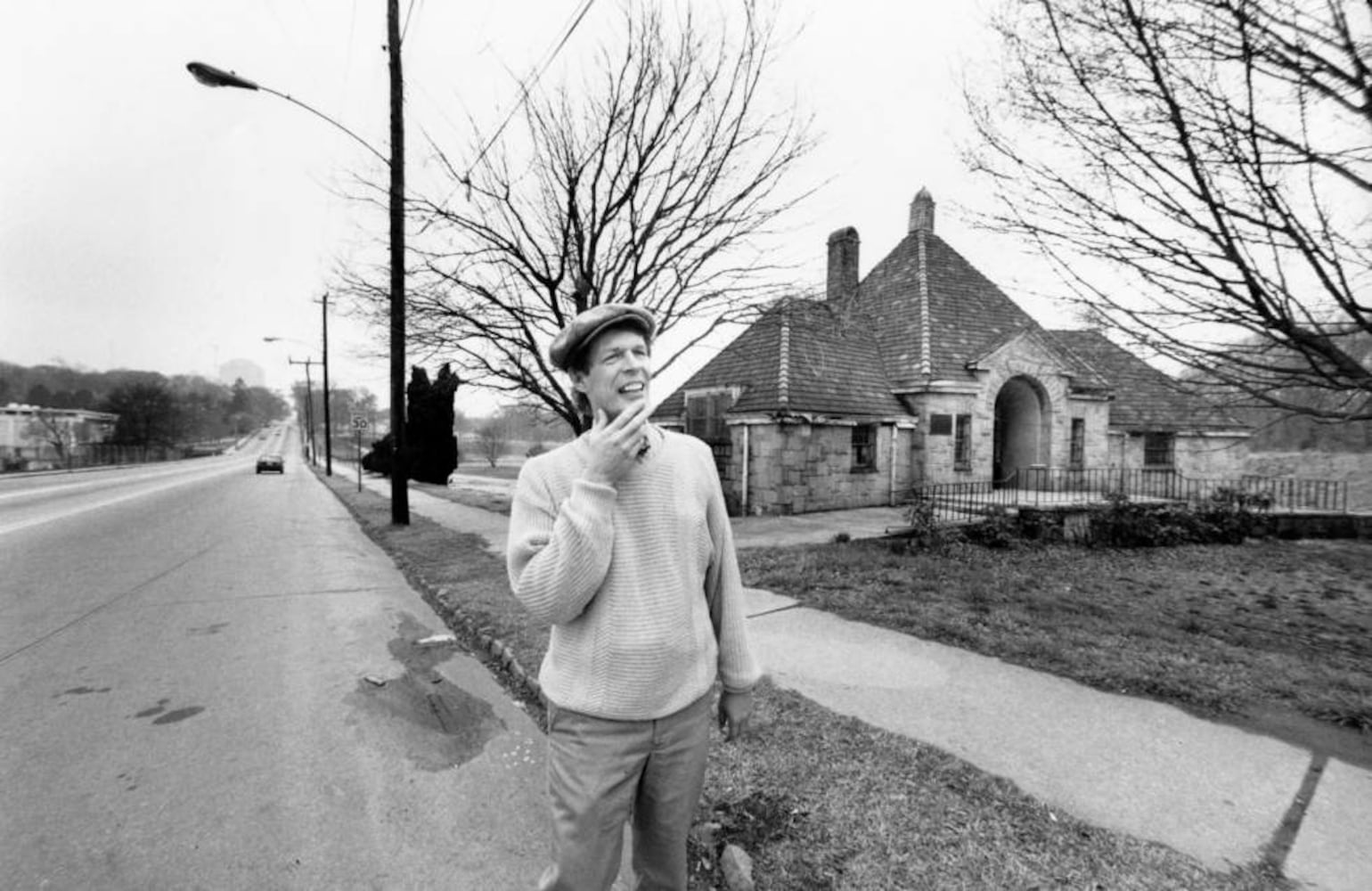

“One of the remaining architectural parts of the 1895 exposition are those stone steps and stone plant containers,” Rose said.

Five years of sitting untouched after the city purchased the land, the Olmsted Brothers — the son and nephew of famous landscape architect Frederick Law Olmsted who designed Central Park in New York — redesigned the park.

It had both trolley and rails services. Today, a rail line runs along the eastside of the park that existed at the time.

“I think when people walk through the park, they probably think the land has always looked this way,” Catron said. “But they shaped the land intentionally. It was designed to hold hundreds of thousands of people.”

What followed was a rapid period of growth and history of the park as a epicenter for change.

Credit: Steve Schaefer

Credit: Steve Schaefer

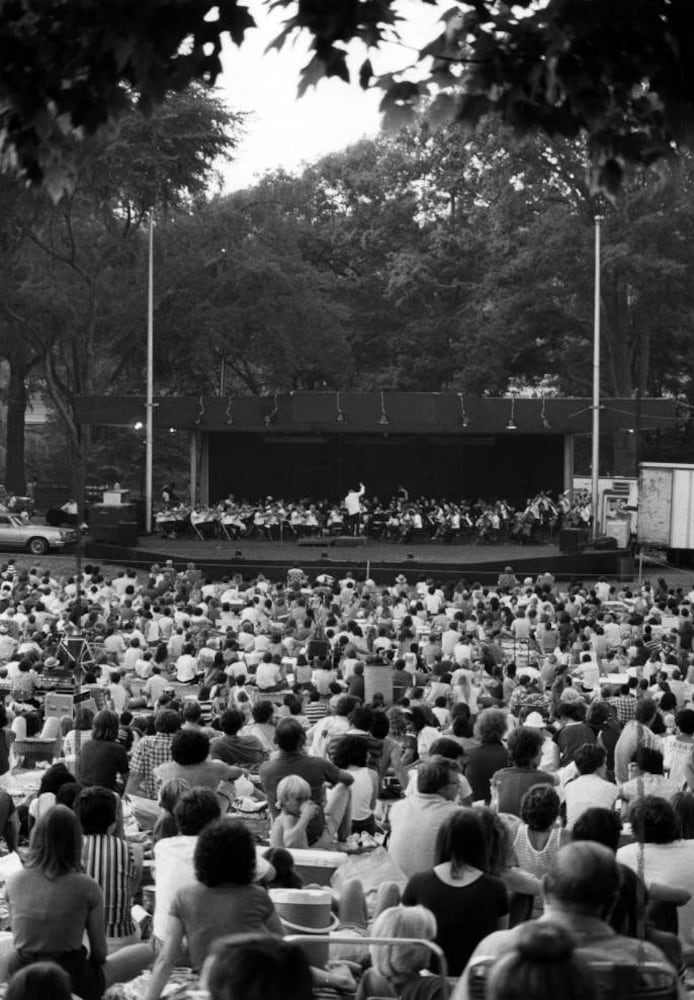

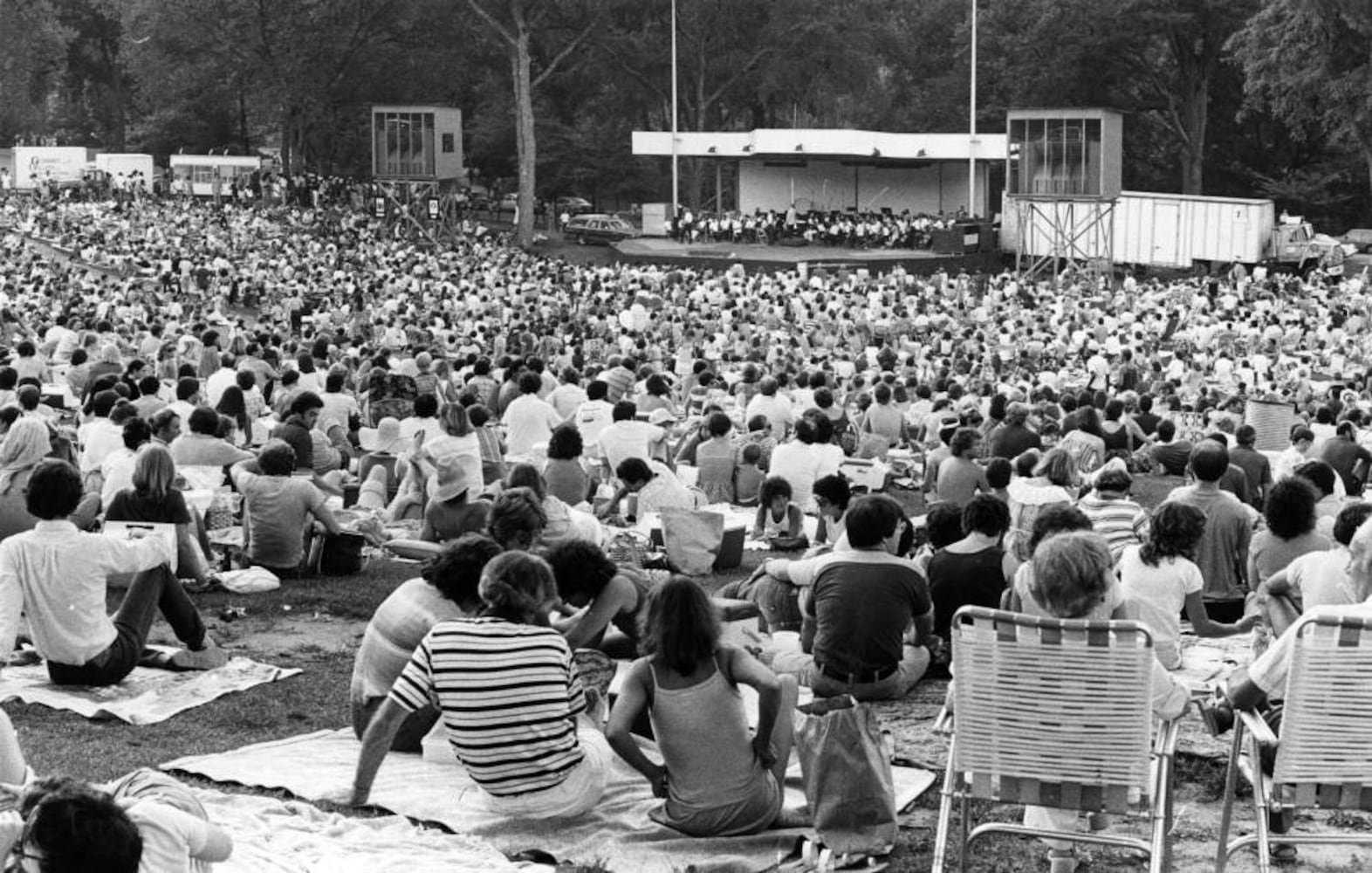

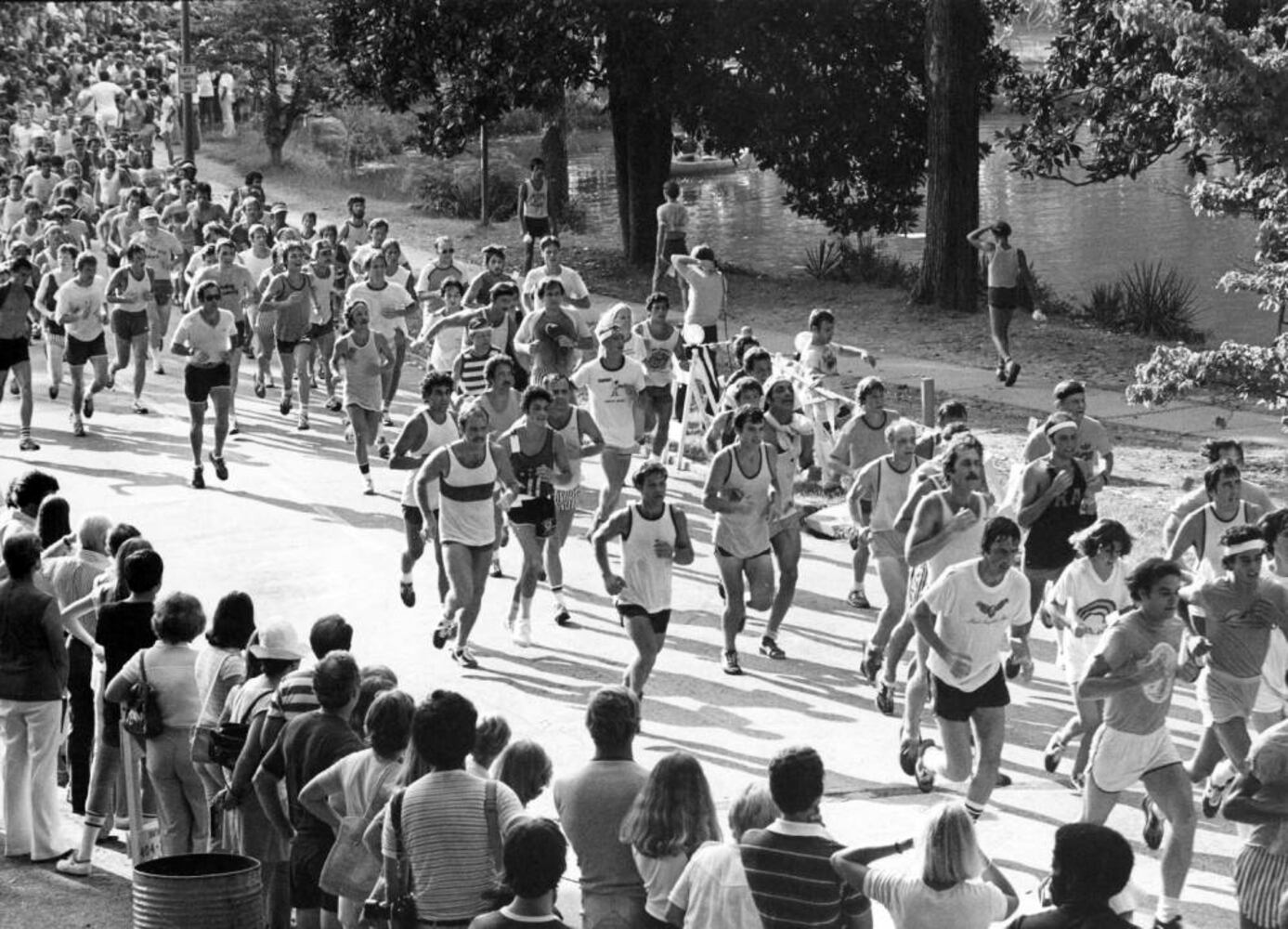

Atlanta was home to a thriving community of hippies on the edge of the park. On Sept. 21, 1969 a riot erupted when political radicals of the time clashed with police during a free concert.

Many others throughout the years have marched through the park and demanded social change — from protests against the Vietnam War and rallies against the AIDS epidemic to Civil Rights movements and calls for stricter gun control.

“The park’s 20th Century story from the late 60s forward is about: how are we going to push our city forward?” Catron said. “For all of the communities that live in it.”

Credit: Miguel Martinez

Credit: Miguel Martinez

Plans for the future

Since it’s inception 35 years ago, the Piedmont Park Conservancy has raised and invested over $110 million in the park. That includes improvements to Oak Hill and the meadows where festivals are hosted, historic building restoration and a revamp of the Active Oval where the sports fields are located.

The organization also funded the North Woods expansion which grew the park by 40 acres — that encompasses the much-loved dog park. On top of that, Widener said, the conservancy takes care of about 75% of the park’s day-to-day maintenance.

“Great cities have great parks,” he said. “In the future, Piedmont Park will continue to be, even more so, an important urban respite in the midst of an even more dense, populated city.”

Credit: Seeger Gray / Seeger.Gray@ajc.co

Credit: Seeger Gray / Seeger.Gray@ajc.co

Since August, the conservancy has been calling on the public to share their dreams for the park as part of a long-overdue comprehensive development plan. Whether that’s as simple as better lighting or as daunting as additional trails — ideas already submitted even include adding paddle boats to Lake Clara Meer.

Widener said they’ve connected with around 10,000 residents since the undertaking began.

Also on their list is an ambitious, multiyear goal: creating an inventory of all the park’s 7,000 trees.

As the window for input into the park’s comprehensive development plan closes, Widener said the conservancy is prepared to reevaluate “every square inch” of the park.

“We have a very good problem in our city that we’re projected to have a very significant population increase in the next 25 years,” he said. “But how we respond to that, how the city grows, is going to really dictate it’s long-term future.”

About the Author

Keep Reading

The Latest

Featured