Although hackers affiliated with the notorious LockBit ransomware group threatened to release sensitive personal information stolen from Fulton County, commissioners decided they could not in good conscience use taxpayer dollars for ransom, county Commission Chair Robb Pitts said Tuesday afternoon.

The cyberattack more than three weeks ago took many county systems offline, and LockBit’s site on the dark web displayed screenshots of internal county documents. A countdown clock said more would be released, including personal data, if an unspecified ransom wasn’t paid. As the deadline passed Fulton County’s information disappeared, and no more was released although countdowns for other targets remained. That led to widespread speculation that the county, or its insurer, had met hackers’ demands.

“We did not pay, nor did anyone pay on our behalf,” Pitts said during a five-minute briefing. “We cannot speculate as to why LockBit removed Fulton County from their website last Friday.”

He reaffirmed the attack was a “ransomware incident,” identifying LockBit as the group claiming responsibility — and went on to thank the FBI and international law enforcement agencies that “acted to significantly disrupt the LockBit group” on Monday.

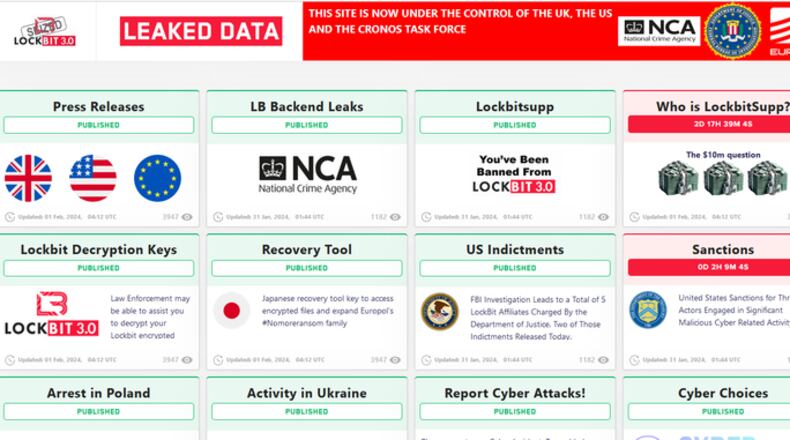

Police in 10 countries, including the FBI in the U.S. and the National Crime Agency in the United Kingdom, on Monday froze 200 cryptocurrency accounts tied to LockBit and the site on the dark web that it used to threaten victims and publish data.

Fulton County’s own investigation into what information might be compromised continues, in cooperation with law enforcement, Pitts said. The county wants to be transparent, but it’s still unclear whether residents’ personal information really was stolen, he said.

If it was, the county will notify those affected and provide resources to protect them, Pitts said.

“I cannot say enough how seriously we are taking this situation,” he said. Pitts and other county officials took no questions.

The FBI has announced charges against five people so far related to LockBit, with two suspects in custody. None of those suspects appears to have any connection with the Fulton County hack.

Separate from the charges in the U.S., Europol said two LockBit actors have been arrested in Poland and Ukraine at the request of the French judicial authorities.

Participating agencies announced some details early Tuesday morning.

“It is difficult to say exactly how many victims of LockBit there are, but we estimate that in 2023 alone there were 1,000 victims just in the United States,” FBI Deputy Director Paul Abbate said in a short video posted on X, formerly Twitter. “The FBI is currently reaching out to each of the victims we know about to share possible decryption capabilities.”

The attack on Fulton County crippled many systems, including hundreds of phone lines. County services were unavailable for several days, and many offices are still using offline work-arounds. About half of the county’s phones are working again, and early voting started Monday for the state’s March 12 presidential primary, Pitts said.

County officials remained mum as to the cyberattack’s nature for days, and cybersecurity experts told The Atlanta Journal-Constitution it was likely the county’s insurance had paid off the hackers in cryptocurrency.

Police agencies are offering decryption tools to victims. The decryption tools may be useful for Fulton County, but that’s iffy, said Bill Hopkins, IT director for Keizer, Oregon, which paid $40,000 in cryptocurrency after a 2020 ransomware attack.

“Each decryption would be totally different,” he said. When Keizer was attacked, the city had to get a separate “key” from the hackers for each encrypted server, Hopkins said.

LockBit has targeted more than 2,000 victims worldwide, demanded hundreds of millions of dollars and gotten more than $120 million, according to the FBI.

Federal authorities unsealed indictments Tuesday against two Russian nationals, Artur Sungatov and Ivan Kondratyev.

“Both Sungatov and Kondratyev are alleged to have joined in the global LockBit conspiracy, also alleged to have included Russian nationals Mikhail Pavlovich Matveev and Mikhail Vasiliev, as well as other LockBit members, to develop and deploy LockBit ransomware and to extort payments from victim corporations,” the FBI announced.

Matveev is on the run, with a reward of up to $10 million for information leading to his capture.

Vasiliev, a dual Russian-Canadian national, is in Canadian custody awaiting extradition to the U.S., the FBI said.

In June, Russian national Ruslan Magomedovich Astamirov was also charged. He is in a U.S. jail awaiting trial, the FBI said.

LockBit’s tools to steal and encrypt data emerged from Russian-language hacking forums in 2020. By 2022 it became the most widely used ransomware, according to police.

“The group provided ransomware-as-a-service to a global network of hackers or ‘affiliates,’ supplying them with the tools and infrastructure required to carry out attacks,” the NCA said.

Europol said LockBit would normally take one-quarter of the ransom affiliated hackers collected.

Europol announced the action took down 34 computer servers in the Netherlands, Germany, Finland, France, Switzerland, Australia, the United States and the United Kingdom.

Agencies will be sifting through the seized data to target LockBit’s leaders, developers and affiliates, according to Europol.

“The Agency has also obtained the LockBit platform’s source code and a vast amount of intelligence from their systems about their activities and those who have worked with them and used their services to harm organizations throughout the world,” the NCA said. But the agency acknowledged this action, though major, does not destroy LockBit.

It’s heartening that authorities have made some progress against LockBit, but Monday’s action was the “tip of an iceberg,” said Doug Milburn, founder of 45Drives, which created SnapShield, software that constantly scans computer systems for behavior patterns typical of cyberattacks.

He and Hopkins said it’s likely the hacking group will re-form within a few months, and though LockBit is the largest player in ransomware it’s far from the only one.

Ransomware software changes constantly, but basic methods remain the same, Milburn said.

Hopkins said antivirus protection isn’t enough; computer users, whether government or corporate, need multiple layers of defense — starting with policing the user behavior that gives hackers access to systems.

About the Author

Keep Reading

The Latest

Featured