Amid signs virus hitting African Americans hardest, many see a pattern

For Barry Wright, COVID-19 greeted him with a slight tickle in his throat on March 19. As the beautiful spring Saturday progressed, the tickle turned into a cough that wouldn’t go away. Then a hack and total congestion by bedtime. He could barely get out of bed on Sunday.

“I am usually pretty healthy,” said the 53-year-old Wright, who goes to the gym three times a week. “So, by the time I called the doctor, I knew something was wrong. I just knew I had it. And how I contracted it? I will never know.”

For Nikema Williams, the coronavirus came slow, but hit hard. The state legislator and head of the Georgia Democratic Party came home from the Capitol on March 16 after an eight-hour session feeling run down. When she couldn’t find something to take her temperature after her fever spiked, her husband used a meat thermometer.

“I went to my primary care doctor and I could barely walk in,” Williams, 41, said last week. “I thought I was going to die.”

The coronavirus has killed more than 75,000 Americans, in a pandemic that has touched every corner of life.

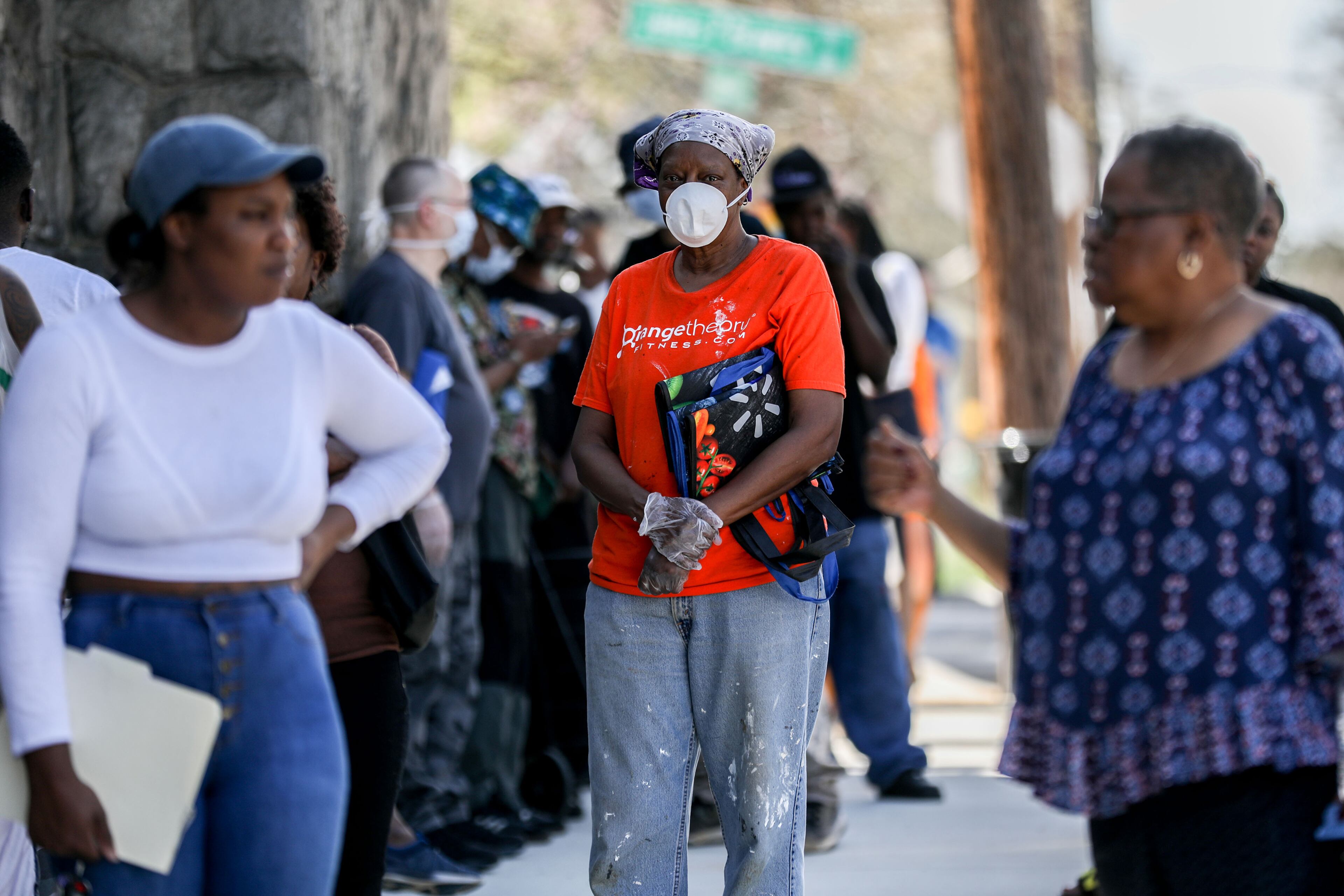

But there is mounting evidence that African Americans — including Atlanta residents like Wright and Williams — are being hit much harder.

Data is incomplete but troubling. Disproportionately black counties constitute only 22% percent of U.S. counties but account for 52% and 58% of COVID-19 cases and deaths, respectively, according to a study by epidemiologists and amfAR, an AIDS research nonprofit.

In Georgia, a very limited study from the Centers for Disease Control and Prevention found African Americans made up 83% of 305 Georgians who had been hospitalized with COVID-19 and whose ethnicity was known.

A broader sampling of incomplete state data suggests that, in cases where the race is known, black males make up 33.47% of positive male tests and black females make up 39.56% of positive female tests. Georgia’s population overall is about 32.4% African American.

Many African Americans aren’t surprised when they see numbers showing a disproportionate impact from the pandemic.

Ed Garnes, the founder of From Afros To Shelltoes, a community-based organization that promotes social change, said any discussion of COVID-19 must address how blacks have endured multiple, deep-seated traumas dating back centuries.

“COVID-19 lays bare the system has always been broken for black folks,” Garnes said. “Think about the psychological impact of knowing, even in a pandemic, your life means nothing, and your humanity as a black person will never be affirmed.”

The talk on social media, academic circles, book clubs and even barbershops – which Gov. Brian Kemp reopened April 24 — suggests the disproportionate numbers rest in racial disparities dating back to Jim Crow. They include African Americans not having jobs they can do from home, less wealth and access to health care, and pre-existing health conditions like diabetes, obesity, asthma and high blood pressure.

COVID-19 is a “heat-seeking missile to those who are chronic and structurally disadvantaged,” said Camara Phyllis Jones, an epidemiologist and adjunct professor at Emory University and Morehouse School of Medicine.

“We are more likely to die because we are more burdened by chronic disease and living in hyper-segregated, disinvested, actively neglected, poisoned communities, often out of sight from those people refusing to look,” said Jones, the past president of the American Public Health Association.

Nonelderly black Americans were one and a half times as likely to lack health insurance as whites in 2018, according to the Kaiser Family Foundation.A study by McKinsey found black Americans more likely to occupy low-paying jobs like cashiers, food service and janitors — jobs that can't be done on a laptop from the safety of home during a pandemic.

When Gov. Kemp moved to reopen the state's economy earlier than other states, and while coronavirus continued to spread, many African Americans saw that as an attack on black and poor people who would be in harm's way in those frontline jobs.

On the first weekend after lifting the shelter-in-place, heavy crowds – black and white – gathered across Atlanta to watch the Blue Angels fly over the city, hang out at Piedmont Park, or gather in line at a mall to grab the latest edition of Air Jordans.

“It is heartbreaking watching that because I know what this virus can do,” said Rep. Williams. “ People are following the lead of our leaders and our leaders have failed us.”

Jones, who is living in Cambridge, Mass. on a Harvard University fellowship, said she is afraid to return home to her family in Atlanta.

“We are not even near the level of testing or the approach for me to feel confident coming back,” Jones said.

Civil rights and social justice organizations, like the coalition that sent Kemp a letter Wednesday, have called for greater government action to protect vulnerable populations. On Mother's Day, New Birth Missionary Baptist Church planned to provide free, drive-thru COVID-19 testing.

As the coronavirus gained steam, social media sprung theories that it was part of a government experiment. Early nonsense that blacks couldn’t get coronavirus has been replaced with claims that the government is trying to kill black and poor people.

But the foundation of conspiracy theories is often rooted in history.

In the Tuskegee Experiment, which ran from 1932 until 1972, the government deliberately didn't treat hundreds of Alabama black men infected with syphilis to study the impact of the disease. As recently as 2017, a civil rights commission in Michigan concluded systemic racism helped cause the Flint water crisis.

“This system doesn’t care about poor people and people of color,” said Charles Steele, president of the Southern Christian Leadership Conference. “Racism is an invisible enemy. What Kemp did was no less than what took place in Tuskegee. It is gonna be death.”

Sherri Daye Scott is making a grassroots effort to prevent that. The writer and producer gathered her artist friends like Tracy Murrell, Fabian Williams and Fahamu Pecou to start Big Facts, Small Acts "to push home the message that COVID-19 is impacting our communities the hardest."

The group’s website has CDC-vetted information and artists have placed signs and murals around black communities, reminding people to stay vigilant.

“There is a lot of misinformation in social media. We have to do better,” Scott said.

Wright, who is recovering from COVID-19, is convinced the pandemic is exposing systemic racism. But he also said people have to do more to help themselves. He wears a mask everywhere now and has returned to work as an operations supervisor for a food distributor.

One day he was talking to a younger colleague about the scene at Greenbrier Mall, where people lined up to buy the latest pair of Jordans.

“He told me that he had to have the new ones. It breaks your heart because they just don’t get it,” said Wright. “Because when it gets to us, it runs through us fast. It took me one day and I was out. We have to take this seriously.”

It took Williams — with all of her privilege, knowledge of the pandemic, status as a state lawmaker and no pre-existing conditions — about six days to find out she had the virus after she came down with symptoms. Although she has recovered, she hasn’t left her house since an emergency room visit on March 30.

“I am afraid of catching it again and passing it along. I don’t know what is going on inside of me,” said Williams, who was wearing a gray “COVID-19 SURVIVOR” t-shirt. “I really want people to understand that this happened to me and that the virus is very real. But I am one of the lucky ones. I am a survivor.”

More Stories

The Latest