As King Day approaches, Atlanta’s gay community remembers Bayard Rustin

As another Martin Luther King Jr. Day approached in 2002, Craig Washington, Darlene Hudson and Duncan Teague looked forward to taking their place in the annual march honoring the civil rights leader’s legacy. As proud members of Atlanta’s black gay community, they felt welcomed but they knew, too, that some in this city too busy to hate didn’t want them there.

“It was not a gay pride march,” said Teague. “It was an MLK march with a small contingent of gay men participating. We were verbally harassed as we came down the street. We were in the march knowing we had a right to be there, but others weren’t so sure.”

Still, for years, they braved the cold with the rest of the community to commemorate King’s life, propelled by the spirit of another unwelcome black gay man, Bayard Rustin.

In 2002, though, they wanted to do more than just be present. Aware of the hidden role Rustin had played in King’s development as a leader and in the civil rights movement, knowing how Rustin must have felt, they wanted to honor him, too.

They wanted folks to know that not only were they present, but they’d been in the fight for justice with them all along just as Rustin had been before them.

RELATED: From service projects to parades, here are the best ways to celebrate MLK Day in Atlanta

And so as a prelude to the King parade that year, they launched the Bayard Rustin Breakfast at the now-defunct Atlanta Gay and Lesbian Center.

“We wanted to make sure people understood the sheer enormity of his contribution to the movement,” Washington said. “Not only was he the architect of the 1963 March on Washington, he co-founded the Southern Christian Leadership Conference and expanded King’s understanding about (Mahatma) Gandhi’s nonviolent principles.”

If you haven’t heard much about Rustin, it is because he operated in the shadows. Not because he was still in the closet but because he realized being gay was considered a liability.

“He embodies our experience,” Washington said.

Rustin died in 1987 at age 75.

When Washington, then executive director of the Atlanta Gay and Lesbian Center, and Hudson decided to hold the breakfast in his honor, it was a way for members of the LGBT community to break bread and teach people about Rustin’s legacy, to say, as Washington put it, “whether closeted or not, you and your kind have always had a place in black liberation work.”

“Racist conservatives like Jesse Helms and others used his homosexuality to defame the movement and accuse King of fraternizing with perverts. I read that Adam Clayton Powell threatened to start a rumor that King and Bayard were having sex,” Washington recalled. “They wanted to erase him. This was our chance to hold him up.”

RELATED: Bayard Rustin

That first breakfast drew some 40 supporters, including ZAMI, Georgia Equality, members of Congregation Bet Haverim and In the Life Atlanta organizers of Atlanta Black Gay Pride. They shared an urn of coffee, discussed the contributions of Rustin, James Baldwin, Audre Lorde and other black gay activists for nearly an hour before donning their coats and heading out to join the annual MLK march.

It was a heady moment Washington will always remember.

The next year, the numbers easily doubled, and before long, Washington found himself searching for a larger facility.

It’s a good problem to have.

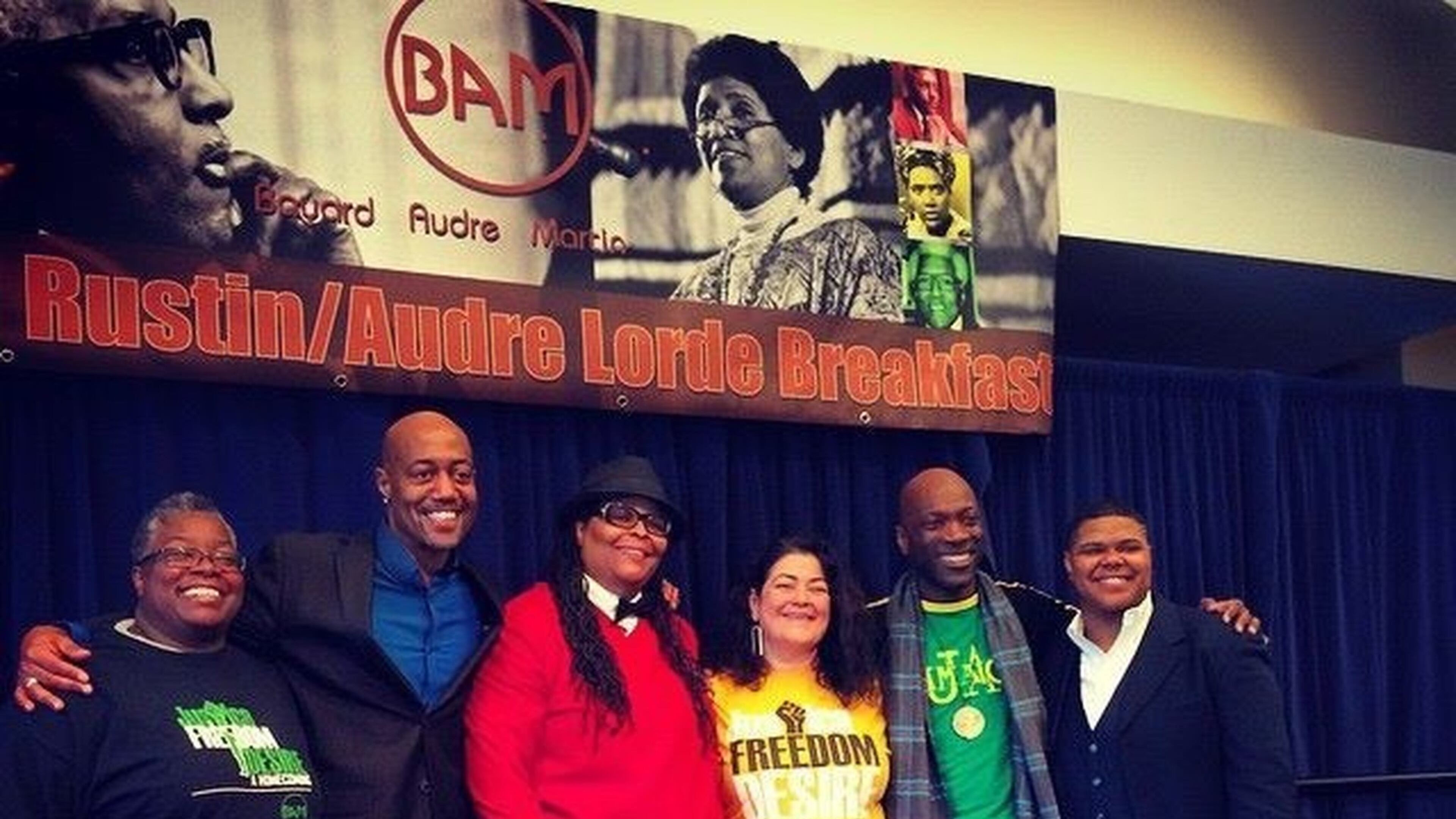

Six years later in 2008, the effort grew in a decided way. Organizers added lesbian activist and poet Audre Lorde’s name, and it even became the Rustin-Lorde Breakfast.

It made sense. Teachings about Lorde at the annual breakfast captivated audiences in the same way lessons about Rustin did.

Plus, Washington was well aware of the risk of having a male-centered event.

RELATED: Counting the cost of being ignored

Slowly the format changed to include panel discussions on hot-button issues, feature films on the life of Rustin and Lorde, honoring other living and departed gay activists, and exhibits on AIDS.

On the heels of Barack Obama’s inauguration in 2009, organizers led a protest against the Rev. Rick Warren’s scheduled speech at the Martin Luther King Jr. commemorative services outside Ebenezer Baptist Church.

They hoisted signs declaring: “We still have a dream: Equality.” They chanted: “Gay, straight, black or white, we demand our civil rights.”

Warren, author of the best-selling “The Purpose Driven Life” and the pastor of an evangelical megachurch in California, helped rally support in California to outlaw same-sex marriage.

Since that first breakfast 17 years ago, the event, now hosted by the nonprofit Southern Unity Movement and held at the Loudermilk Center, draws nearly 400 annually with people registering as early as November.

They are drawn, Washington believes, by a need to remember but also share their collective history and become involved in pushing for needed social change.

“There’s a lot of power and talent in Atlanta, but there needs to be more connectivity, more bridges where we are coming together across differences of age, gender, race, ethnicity and by values and other common priorities and vision,” he said. “I think that’s what people get out of the breakfast. It’s a manifestation of the beloved community.”

Find Gracie on Facebook (www.facebook.com/graciestaplesajc/) and Twitter (@GStaples_AJC) or email her at gstaples@ajc.com.

EVENT PREVIEW

Rustin-Lorde Breakfast

10 a.m. Jan. 21. Free to public. Loudermilk Conference Center, 40 Courtland St., Atlanta. southernunity.org.