For needle-phobic people, flu shot season is ripe with mental tennis matches centered around if it’s worse to get the vaccine or chance the sickness. Georgia Tech and Emory researchers may have found the cure to this seasonal internal struggle: a painless, self-administered microneedle patch.

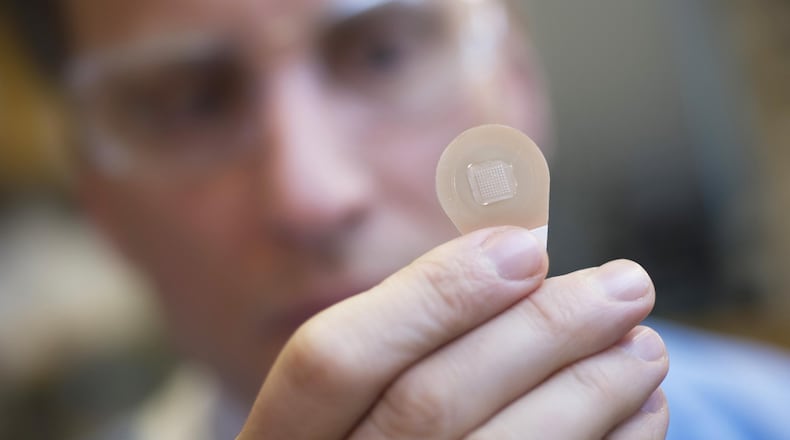

The patch looks like a Band-Aid with teeth. Users press the patch into their skin, where microneedles (the aforementioned teeth) deliver the vaccine before dissolving, leaving no sharps waste behind. Micron Biomedical, a company founded to commercialize the patches, hopes the technology will encourage more people to get vaccinated.

The flu patch, for which Micron is working toward Food and Drug Administration approval, could realistically be in clinics in three to five years.

The Centers for Disease Control and Prevention recommends everyone over 6 months get a flu shot yet only about 40 percent of adults currently do.

“When you ask people why they don’t get a flu shot, some people say they’re afraid of needles and syringes, some say they don’t have the time to go see a doctor or go to the pharmacy to get a shot and some talk about how the flu shot doesn’t work as well as it could, so why get a flu shot,” says Micron Biomedical co-founder Sebastien Henry. “What the patch does is it helps with all of the issues I’ve mentioned.”

A Georgia Tech study found participants more likely to get vaccinated if the microneedle patch were an option. The patch is painless, with users reporting only slight redness or itchiness at the injection site. Unlike traditional vaccines, the patch doesn’t need to be stored in a refrigerator. People may eventually be able to have the patch shipped to them, severely cutting the time required to get vaccinated.

“It’s easy for people to administer the patch at home, whether it’s to their children or an elderly person who might not be able to apply the patch themselves.” Henry says.

A phase one clinical trial conducted by Emory University in collaboration with Georgia Tech researchers found the microneedle patch safe and effective, a major steppingstone toward getting the technology approved by the FDA. Study participants were randomized into four groups. One group was given the microneedle patch by health care providers, and another was asked to administer the patch themselves. A placebo patch or traditional shot was given to members of the final two groups. The study showed that the patch and shot generated similar immune responses in participants. Results were published in The Lancet, a medical journal, in June of this year; Emory associate professor of medicine Dr. Nadine Rouphael was first author and principal investigator.

“Over the years, graduate students made research progress to the point where we’re now able to evaluate it in a phase one clinical trial,” Henry says.

Georgia Tech is a research institute; the university heavily encourages students participate in professors’ research. Henry started working on the project as a master’s student and contributed research to the first peer-reviewed paper on microneedles published by Georgia Tech in 1998. Henry, fellow Georgia Tech graduate Devin McAllister and Regents’ Professor of Chemical and Biomedical Engineering at Georgia Tech Mark Prausnitz founded Micron Biomedical to commercialize and make their research available to the public.

Henry says, “It’s a very good example of research that is developed in a public setting, and then a company spawned to translate this research into an actual vehicle that can help millions of people.”

About the Author

Keep Reading

The Latest

Featured