When she was a graduate student at the University of Massachusetts, Amherst, one of Natasha Trethewey’s poetry professors told her that she should stop writing about her “dead mother.”

His suggestion implied she should train her talents on issues he believed were larger, more universal. He suggested the then-conflict in Northern Ireland.

It had barely been a decade since Trethewey’s mother, Gwendolyn, was murdered by her second ex-husband outside her apartment in DeKalb County in 1985. He shot her once in the face, once in the neck. One of the bullets passed through her right hand, as if a defense wound.

Perhaps the professor (who Trethewey declined to name in an interview I did with her eight years ago for a profile) did not realize the violence he inflicted on a young woman still tending the wound of grief. Her mother’s death was a horrific outcome of domestic abuse that Trethewey could not have prevented. Poetry didn’t soothe the ache of loss and guilt so much as express it.

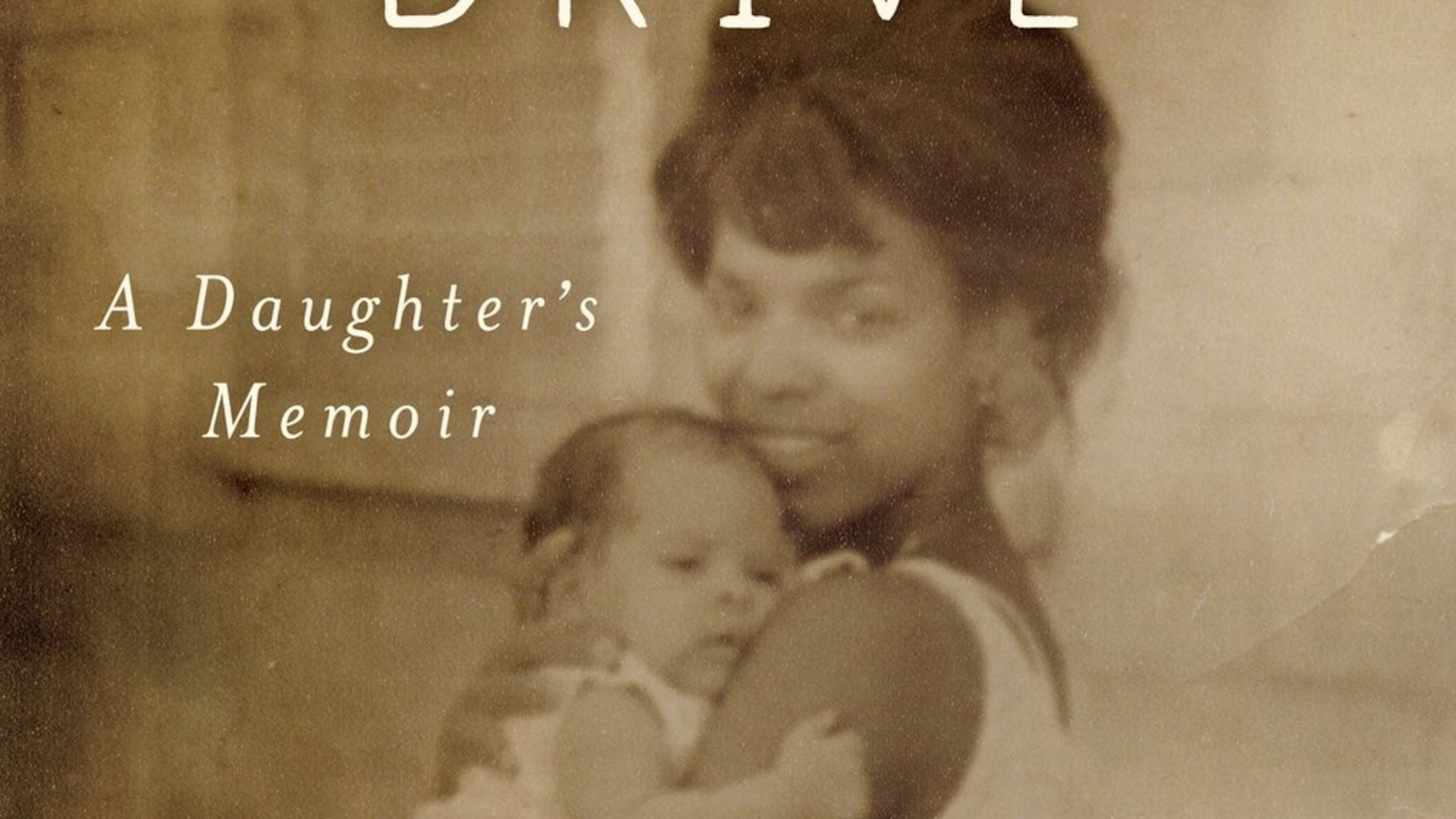

In the ensuing 30 years, she won a Pulitzer Prize and was named the 19th poet laureate of the United States. Yet in verse and in private, she never ceased mourning. Only in her new book, “Memorial Drive: A Daughter’s Memoir,” does she face the atrocity of her mother’s murder in its entirety. It is written with great beauty and delicacy. It is an accounting, not a healing.

The role of metaphor looms large in this book, beginning with its title. The apartment complex where her mother was murdered still stands on Memorial Drive near Stone Mountain. The poet went back there just a few years ago, she writes, as a starting point for this memoir, a necessary but dreaded visit.

Told in first person, second person and through chilling court transcripts, the suffering of mother and daughter is harrowing. Though not visited on her physically, the psychological abuse her mother’s second husband inflicted on Trethewey lasted 13 years until she left to attend the University of Georgia.

“When I left Atlanta, vowing never to return, I took with me what I had cultivated all those years: mute avoidance of my past, silence and willed amnesia buried deep in me like a root.”

Now she lays it bare and unbroken across 224 pages.

Readers of her five volumes of poetry and her previous book of prose, “Beyond Katrina: a Meditation on the Mississippi Gulf Coast,” already know bits and pieces of her personal narrative. She was born in Mississippi on Confederate Memorial Day in 1966, the daughter of a Black, Southern mother and white, Canadian father. Her home state’s anti-miscegenation laws, as she has said, made her existence a crime.

As in previous work, in “Memorial Drive” we meet Trethewey’s maternal Mississippi family who reared her with joy and care through her preschool years: Aunt Sugar, who taught Trethewey to fish; Uncle Son, the handsome, industrious nightclub owner; and Trethewey’s grandmother, Leretta Dixon Turnbough, a seamstress who retired to help take care of her granddaughter.

The day Trethewey and her mother leave North Gulfport, Mississippi, for Atlanta in 1972, after her mother’s divorce, Turnbough tells her granddaughter that she is “an easy child to love.” From birth to six years old, the author’s extended family showered her with the same affection.

Trethewey renders those stories in first person with tenderness, reverence and a sense of wonder. They are the few respites in the narrative. Once her mother remarries, the abuse rapidly escalates. At night, Natasha hears her mother pleading not to be hit again. In this telling midway through the book, Trethewey switches to second person, a device she acknowledges was necessary for her to bear witness. Rather than bring a reader closer, however, the switch puts them at some remove. Until then, the reader is walking by her side, wanting to protect this child from what will come.

Survivor’s guilt suffuses each chapter. She wonders if an off-hand gesture she made toward her mother’s husband saved her but ultimately doomed her mother. Had she told more people about what was happening, would things be different now? Over the years, forgetting and erasure became coping tools. Those themes are abundant in her work as is the concept of remembrance. For those who seek to conquer demons, remembrance is the most terrifying of all necessities.

But why did Trethewey write this now? Was she at a breaking point where she could no longer shoulder the load without sacrificing her emotional future? At 54 years old, she has carried the weight of June 5, 1985 — the day her mother died on the pavement of her apartment parking lot — her entire adult life.

She writes about what it is “to become intimate with one’s own bereavement.” Then she continues with a line that brings to mind the opening of Zora Neale Hurston’s masterpiece, “Their Eyes Were Watching God,” where Hurston compares the nature of dreams and fate to ships on the horizon. Of the enduring nature of her sorrow, Trethewey writes: “You get used to it. Most days it is a distant thing, always on the horizon, sailing toward me with its difficult cargo.”

This is the full telling, but will it lead to a healing? Maybe, for now, saying it out loud and with devotion, is enough.

NONFICTION

‘Memorial Drive'

by Natasha Trethewey

HarperCollins

212 pages, $29.99