Despite progress, HIV remains disproportionately Black in Georgia

Fred Bryant has a recurring problem these days at festivals and community meetings.

Whenever he sets up a table for HIV and AIDS awareness at functions targeting the Black community for health intervention and treatment group Aniz, there are always a couple of people who stop by in hopes of getting a COVID-19 test.

As soon as they discover their mistake, they panic.

“When we’re out in the community setting up our table, people walk by and inquire, ‘Are you guys doing COVID testing?’” he said. “We say, ‘No, we’re doing HIV testing.’ And the reaction is, they want to take off running from the table.”

Forty-one years after the first cases of human immunodeficiency virus were reported, HIV still strikes terror in many people, and it has become a critical problem in Georgia’s Black community.

After decades of public health campaigns to battle the virus, Black Georgians — especially those in metro Atlanta — still make up a disproportionate percentage of HIV infections in the state, public health officials say.

Though African Americans make up only about 32% of the state’s population, around 71% of the roughly 2,500 Georgians who were newly diagnosed with HIV in 2019 were Black, according to the latest statistics from the Georgia Department of Public Health.

New medications that make it more difficult to infect someone with the virus are not helping bring down the number of new infections, health officials said. And too many Black Georgians who are positive do not take anti-viral meds that make transmission all but impossible.

“We have the science, the technology to, in my opinion, eradicate new infections,” said Nicole Roebuck, executive director of AID Atlanta, one of the state’s largest HIV/AID prevention organizations. “Why doesn’t everybody have access?”

Of the 750 people who died from the virus in 2019, 69% were black compared to 20% who were white and 4.5% who were Latino. About 58,600 of all Georgians were living with the virus in 2019, the state health department said.

“We’ve built a healthcare system that works pretty darn well for the white people and wealthier populations,” said Dr. Jonathan Colasanti, medical director of the Grady Ponce de Leon Center. “But it’s not working for all groups. And if the system isn’t working, then we have to rethink the system.”

Thinking it through

Part of the reimagining is already underway.

For years most of the organizations fighting the virus were located in Atlanta. But organizations such as Positive Impact Health Centers have opened branches in Decatur, Duluth and Marietta to address needs beyond the city, especially as gentrification has pushed many Black people out of Atlanta.

Support also is available in Clayton County, one of the communities hardest hit by the epidemic, and in rural Georgia, with Athens, Macon and Augusta acting as testing and treatment destinations.

Efforts also have broadened to address the HIV care needs of transgender women, who make up a fraction of the population but are over-represented in diagnoses. Georgia Department of Public Health interviewed 144 trans women, a small sampling of the community, for the first time in 2020 and found that 54% were HIV-positive. Among that group 64% were Black.

Queen Hatcher-Johnson, gender inclusion manager at Positive Impact, said Black women face tremendous hurdles getting tested or treatment if they are positive. Those challenges include safely getting to testing sites, taking time off for visits from low-paying jobs and dealing with medical staffs that mis-gender them or call them by their birth names.

“All of this keeps people out of care,” said Johnson, a transgender woman. “We are intentional about having gender-affirming clinic days. We also have extended hours for people who can’t get off during the regular workday.”

Metro Atlanta is considered by many to be a mecca for Black gays, which have been disproportionately impacted by HIV, especially in Fulton, DeKalb and Clayton counties. And the use of pre-exposure prophylaxis, or PrEP, a once-daily pill that reduces the risk of catching the virus, is low among Blacks, even though awareness of the drug is relatively high.

In its 2019 profile of the epidemic in Georgia, the health department said men made up 75% of the people infected with HIV or AIDS and most — 61% — were men who had sex with men.

About 68% of the infected were Black and 65% were 40 or older, a testament to the life-saving drugs that have made HIV a chronic condition instead of a death sentence.

Peter Byrd is one of those Black male survivors of HIV. Byrd, a 66-year-old Douglasville resident, learned he was HIV positive 33 years ago and has not had an easy battle. In the early days of his fight, he gained and lost weight and has been near death.

One crisis in particular sticks out in his mind. It was 10 years after his diagnosis in 1989, and he had become so ill that he had to be hospitalized. Living in Baltimore at the time, he thought he had reached the end.

But days after his hospitalization, he recovered and the medical center sent him home with multiple bottles of medication.

“It was so invasive that I used to sleep in the bathroom because I really couldn’t walk, I was a skeleton,” he said. “I laid a pillow down at the toilet so when the medicine came up I didn’t have to run to get to the bathroom.”

More than two decades later, Byrd is now down to one pill a day.

Bridging the gap

The reasons the Black community has made little progress vary, health leaders and those with HIV or AIDS said.

Black Georgians who have contracted the virus often lack adequate access to insurance, struggle to obtain housing and food, have trust issues with medical institutions or suffer from substance abuse.

Others decline to test for the virus because of stigma that associates the virus with homosexuality while some Black churches, which hold great importance in parts of the community, have linked the virus with immoral behavior and the accompanying illness with godly punishment.

“There are huge portions of the Black male population that still equate HIV with homosexuality,” said Taurus Jerelds, CEO and founder of Mpowerr Health and Wellness, a health advocacy organization based in Jonesboro. “They are not really understanding or slow to accept the fact that you don’t have to be a Black gay man or a gay male to become infected with HIV.”

Addressing those cultural, institutional and monetary issues are critical to changing the virus’ trajectory, a move Georgia’s leaders have yet to make, health leaders said.

A CDC report from 2019 said infections in Georgia among Black men are 5.9 times higher than white men and 11.4 times higher for Black women compared to white women.

“We have to keep in mind the social determinates of health and those things that impact us,” said DeWayne Ford, director of prevention services for AID Atlanta. “Those with hierarchal needs of having somewhere to live, someone to love, food, those type things.

“And when you are working with a population of people that maybe live outside of those needs or don’t meet those needs, that of course welcomes in any disparity, and HIV is one of them,” he said.

Battling shame

For Aniz’s Bryant, who works as a peer support specialist, testing is personal. Bryant was 37 when he was diagnosed with HIV and remembers how the words hung in the air. He was well acquainted with the virus because he lost eight members of his family to HIV and thought he, too, would succumb.

“The first thing I thought was, I was going to die,” he said. “I disclosed to my immediate family right away. I think that made it easier for me to talk about it out loud.”

That was in 2009, when Bryant took a cocktail of four pills a day to keep himself healthy. Today he is down to one pill a day and wants those who become infected to know there is hope.

“Now I’m having a conversation with my doctor about taking one shot a month as opposed to one pill per day,” said Bryant, 49.

Tammy Kinney’s challenge is strikingly different in rural Georgia.

The Winder resident, who was diagnosed with HIV in 1987, focuses her advocacy on rural Black women with the virus. She said rural Black women are even more reluctant than their city counterparts to address their status, which can lead to dire consequences such as late HIV.

Late HIV generally happens when failure to test allows the virus to progress and CD4 T-cell counts fall dangerously low. About one-quarter of rural Georgia women with the virus had late HIV in 2018 compared to about 19% in metro communities, she said.

“Black women love to be in relationships because we’re nurturers,” she said. “We desire love and we give love. But then disclosing their status in a relationship is very hard.”

As an example, she said she once lead a group of 45 women who had gathered to discuss untreated trauma. Initially about seven of the women disclosed their HIV positive status. But as the group dug deeper, she learned that least 22 of the women were HIV positive.

“It was heartbreaking because the women didn’t know how to disclose their status,” she said.

Censorship matters

HIV/AIDS is not the only health issue facing the Black community, health advocates point out. Black people suffer from high incidences of hypertension, diabetes, heart disease and obesity.

And stigma impacts decisions in other Black health issues, such as Black men and colonoscopies.

But HIV/AIDS stands out because it requires discussions about sex and intimacy, which often make people uncomfortable, especially in areas where the conversation could be most effective, such as schools, health leaders and those with HIV said.

Often groups such as churches or community organizations will ask HIV awareness advocates to speak about the virus but demand that they censor words like “condoms” or “gay” from the discussion.

“We can’t receive funding from certain people because of our mission statement or vision,” Aniz’s Bryant said, “because we talk substance abuse, we talk about mental health, and we talk about sex.”

Oliver Clyde Allen, bishop of The Vision Church of Atlanta, which has been a leader in the fight against the virus, sees changing the course of Black HIV/AIDS as not just about resources, but a desire to bring the problem to an end.

“If there is no will, there is no solution,” he said.

A lot of Georgia’s HIV challenges could be addressed if the state expanded Medicaid, which would allow healthcare coverage for those who fall through the funding or insurance cracks, he said.

“Medicaid is a structural public health dynamic that’s much larger than a clinic’s ability to serve the community, or a church providing testing, or banner or a flyer or billboard that talks about PrEP,” he said.

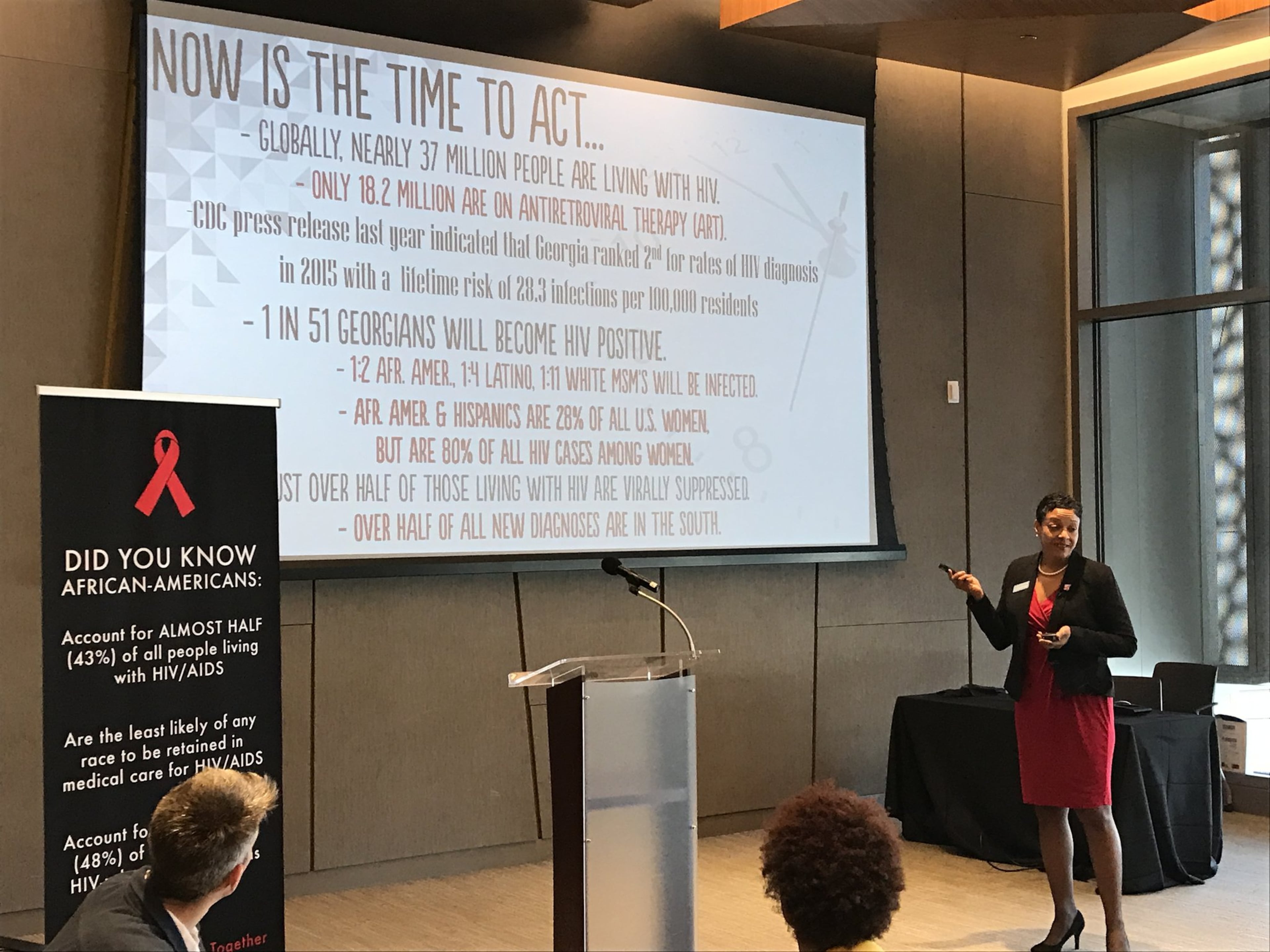

BLACK HIV

71% — Of the roughly 2,500 people who contracted HIV in Georgia in 2019, 71% were Black

69% — Of the 750 people who died from HIV in Georgia in 2019, 69% were Black

64% — About 54% of 144 transgendered women interviewed in a small sampling of Georgia’s transgendered community by the Georgia Department of Public Health in 2020 were HIV positive. Black trans women made up 64% of those with the virus

43% — Of the new HIV diagnoses in the U.S. in 2018, about 43% were among Black people

62% — Just over 62% of new U.S. diagnoses of HIV infections in 2018 among Black men and women were in the South

Sources: Georgia Department of Health, Centers for Disease Control and Prevention

BY THE NUMBERS

AID Atlanta, one of the largest organizations addressing issues of HIV/AIDS in the metro area, said it has served 1,200 case management or care programs for residents with the virus. Here are statistics on the organization’s outreach in the Atlanta community in 2021.

250 — number of people served in housing program

16,000 — number of HIV tests conducted

50,000+ — number of sexually transmitted infections screens, including chlamydia, gonorrhea, syphilis

600 — number of people provided with PrEP

3,200+ — number of HIV postivie people served for HIV specialty medical care services

1,200 — number of people served in case management or coordination programs