90-year-old organ, Mighty Mo, will undergo a year of restoration

A visitor to the Fox Theatre on a drizzly Jan. 2 — a “dark” Thursday — might have seen a rare sight, akin to a do-si-do between Hulk Hogan and Dwayne “The Rock” Johnson.

Rolling from one end of the stage on a four-wheeled dolly was the half-ton Mighty Mo console, the gilded and bedazzled driver's seat from which musicians play the Fox Theatre's world-renown pipe organ.

Coming from the loading dock at the other end of the stage was — what? Another console, equally huge, glittering and gold, with the same four sets of keyboards and the same bewildering array of buttons, tabs and pistons. It was a doppelgänger, a Mighty Mo manqué.

“We’re having an organ transplant,” joked musician Ken Double, master of the Mighty Mo, looking on from a safe distance. “Be careful please,” he cautioned the handlers. “It’s not the time for a fender bender.”

After the two consoles posed together for photographs, the new console, built over the last six months, was installed on the Fox Theatre’s organ elevator, while the 90-year-old Mighty Mo console was bundled into a box truck and whisked away to a Lithonia shop where it will undergo a year of restoration.

Built in 1929, the same year as the Fabulous Fox, the Möller is one of the biggest theater organs in the country, and one of the most famous. Audiences at the Fox are familiar with that moment when the spotlight shines on the wildly elaborate console as it rises from the orchestra pit like some golden chariot, to lead the audience in a rendition of "Tie a Yellow Ribbon" or "Somewhere Over the Rainbow."

But the Mighty Mo is feeling its age. The electro-pneumatic-mechanical switches that trigger its pre-set pistons are plagued with leaky leather valves and balky contacts. Old repairs are coming apart. Paint is flaking and the case is cracking.

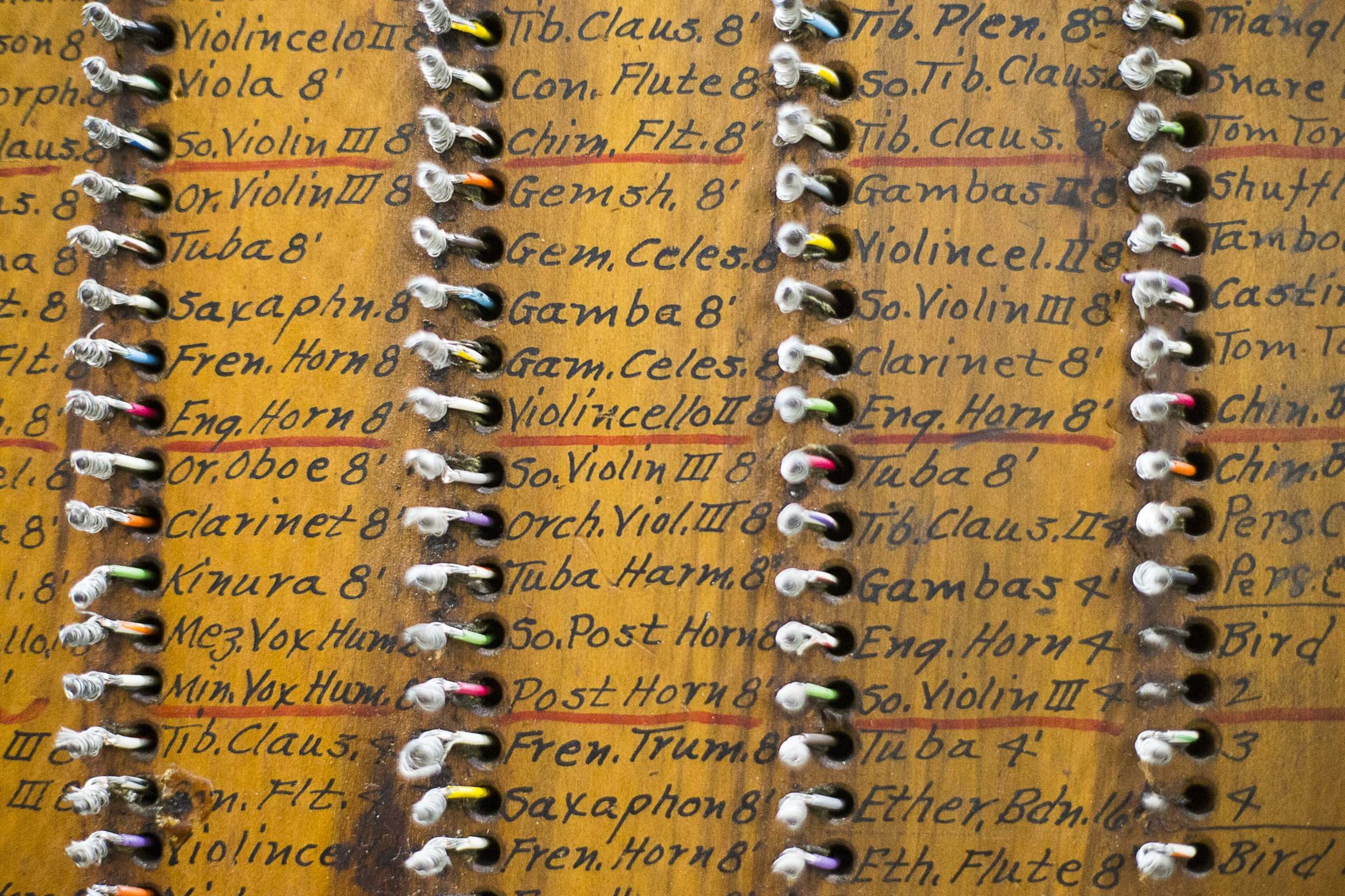

That’s just a matter of age, complexity and wear-and-tear. Each key of the four keyboards and all of the 376 stops communicate with the 3,600 pipes through a thick bundle of 4,000-plus wires that snakes out of the base of the console like a black umbilical cord.

These wires carry impulses that, up in the chambers, trigger electro-magnets which shift leather valves in the wind chests, allowing air to flow through pipes that range from the size of fountain pens to the size of three-story Corinthian columns. (The 32-foot diaphone pipe actually causes the building to shake.)

The combination of switches and valves is a Rube Goldbergian nightmare. “To a certain degree, it’s incredible that they work at all,” said Double, “and it does this in an eyelash of time.”

Archaic technology

Visible inside the guts of the console were scars and repairs from years past, including work done by the late Joe Patten, the original "Phantom of the Fox," who was responsible for restoring the unplayable organ in the 1970s. Patten then galvanized Atlanta's preservation community to save the Fox itself, which was in the path of the wrecking ball.

Because of great service offered to the ornate theater, Patten was granted a lifetime lease to an apartment inside the theater's labyrinthine private area, and he made it his responsibility to keep Mighty Mo in fighting trim.

Shortly after Allan Vella became the Fox Theatre's CEO and president in 2006, the septuagenarian Patten led him on a climb up vertical ladders into the dusty chambers holding the organ's pipes.

“I was able to tap into some of my old rock-climbing skills to get through those chambers,” said Vella.

In addition to its pipes, the Mo is tricked out with a wild array of sound effects and pneumatically-controlled instruments, including a slapstick, a xylophone, drums, gongs, bells, songbirds, ocean waves, a steamboat horn and many others. They fascinated the new CEO.

Such instruments and sound effects were utilized during the heyday of the theater organ, when they were played as an accompaniment to silent films. By 1929, the silent era was waning, and theater organs were on the way out.

The restoration of the organ will cost just north of $500,000, said Vella. The expense is worth it, he said, considering the emotional bond between the citizens of Atlanta and the Fox Theatre’s Mighty Mo. There are few theatre organs in the country with a following as devoted, he said, and “very few organizations put this amount of resources into (preservation).”

At the workshop

Twenty miles away from the Fox, by the railroad tracks outside Lithonia, are four steel beam warehouses that house the A.E. Schlueter Pipe Organ Company.

Recently Arthur Schlueter III, the second generation of pipe organ builders in his family, offered a tour of the facility, as workers soldered wiring and routed planks of wood.

At the center of the action stood the Möller console, looking exposed and less glamorous in the unflattering light of the workshop.

It is here that Schlueter and his father, Arthur Schlueter Jr. built the stand-in organ from scratch, and here that the Möller will be repaired. He said the repairs will be carefully documented. The parts that are replaced — the antique switches, wires and pneumatics — will be stored in the Fox’s archives. “If somebody ever wanted to undo what we did, they can.”

They built the stand-in console so that organ performances at the Fox could continue while the Mighty Mo console is undergoing restoration, Schlueter said, and so that the complex of pipes and valves in the theater’s chambers didn’t stand idle. “If you don’t use a mechanical device, you get atrophy,” he said.

One of the questions that Schlueter has been asked is whether his shop will keep the “patina of age” on the surface of the console. Schlueter points to the cracks, flaked paint, and a burn-mark that looks like someone ground out their cigarette above the bombard. “Do we want to keep all that?”

(Many historic layers of paint have been added to the console since 1929, and Schlueter is studying the records to determine the proper look.)

In one significant change, Schlueter plans to replace the electro-pneumatics inside the console with a computer, which will control the pre-set pistons. The computer will also route signals from the keys and stops to the pipe chambers by way of a slim Ethernet-style Cat 5 cable, replacing that anaconda-sized bundle of wires.

The substitute Mini Mo is currently using this same computer technology. Double, who shares musical responsibilities at the Fox with Rick McGee, said the result is like taking off the handcuffs. Voices and combinations that were difficult to use before are accessible now. “This will unleash the color of this instrument like it’s never been heard before,” he said.

Double is concerned that old school fans will be alarmed by the introduction of the computer interface. But he cautions that the computer is strictly a signal processor. The ranks of pipes will still be voiced by forced air from the blower room, moving past leather valves in the wooden wind chests. There will be no MIDI sounds in the Mighty Mo.

“We will clearly hear from the preservationists, who will express their sorrow that this happened,” said Double, “but this was totally the right thing to do.”