Violent ‘Mexico’ reveals unexpected treasures

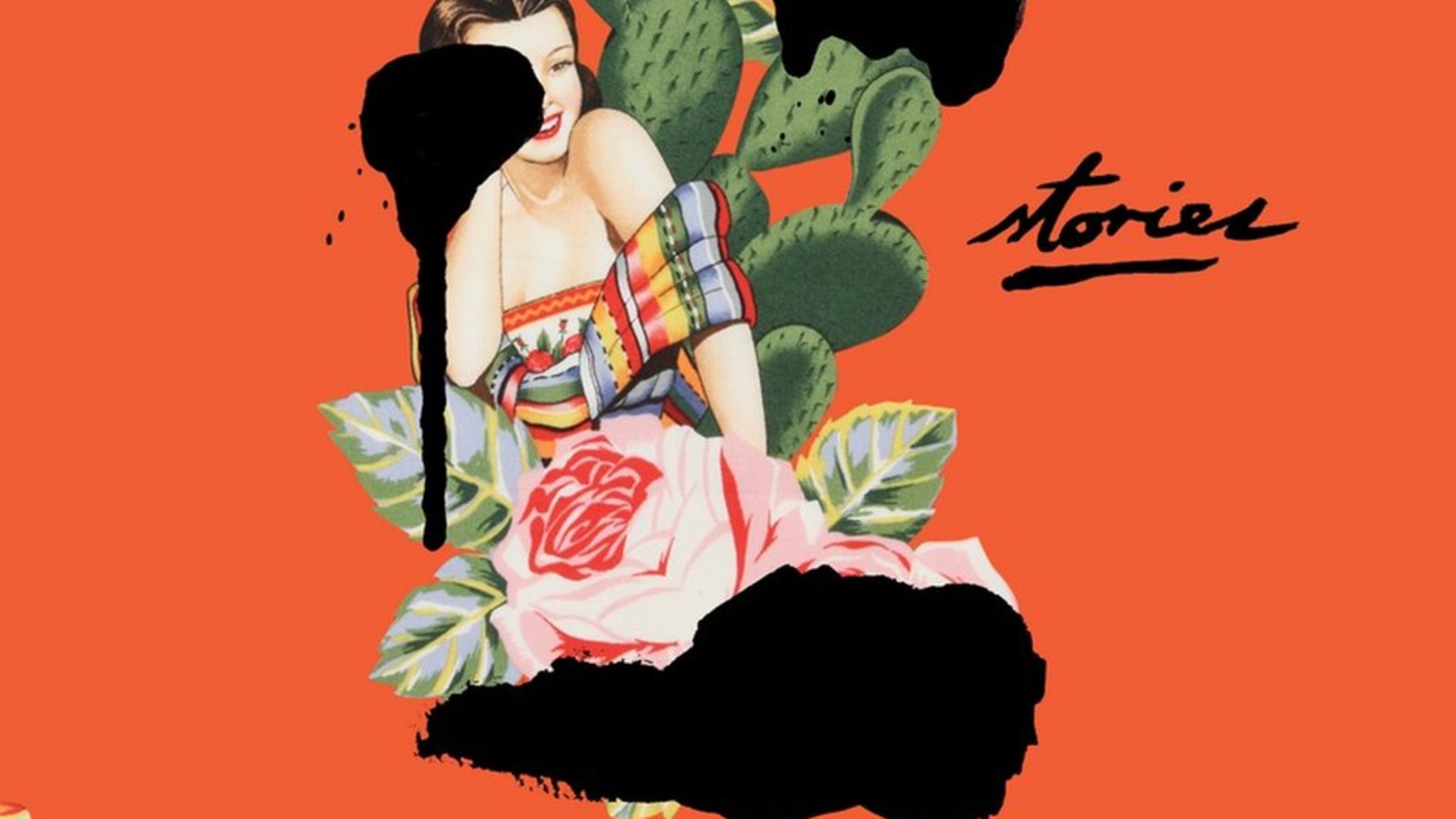

Josh Barkan’s timely story collection, “Mexico,” is like 12 volcanic rocks carefully arranged in the sun, gathering heat. Its smart cover image, lovely and rude — a postcard señorita nestled in rose and cacti, defaced with splotches of black ink — suggests paradisaical allure and unpredictable narco-violence.

It’s a book Josh Barkan really didn’t want to write, but, having once cowered in the kitchen of a Mexico City taqueria during a gun battle, he tells an interviewer, “I felt the need … to convey the kinds of people who are regularly caught up in the violence, but who are rarely covered by the press — painters, teachers, etc. I thought this was a new way to express the violence.”

“Mexico,” then, is Barkan’s invention based on both personal experience and events clipped from the daily headlines. These tales are mostly set in Mexico City, which has a metropolitan population four times larger than Atlanta’s. They are told with confidence and precision, and they share certain commonalties: a direct opening line (“For twenty years I have been a bounty hunter.”) followed by a matter-of-fact complication; then there’s some kind of wild meteor strike before chaos subsides in simplicity and renewal, an old-fashioned moral rising from the debris. (“I was going to do better. I was going to try to make something of my life.”)

As a whole, the book follows a smooth, symphonic arc, rising with the dark whimsy of “The Chef and El Chapo.” An American head chef opens a restaurant in Mexico City, where “people still loved the food for how it tasted and not what it said about them.” El Chapo Guzman, the world’s most notorious drug lord (currently in the U.S. federal prison system) saunters in and demands a special dish in exchange for a sizable tip. “I realized only one thing would make El Chapo absolutely happy,” says the chef. “Human flesh.”

Entertaining absurdities are scattered throughout "Mexico," a country where, at any time, "the surreal becomes the real." In "The Plastic Surgeon," a drug kingpin named Paco dies on the operating table during reconstructive surgery; one of his guards informs the terrified doctor, "No one kills the jefe. Only the jefe can kill himself."

A few of the author’s subjects are Mexican citizens, but the main players are mostly American expatriates, or half-expatriates like Josh Barkan himself, who divides his time between Mexico City and Roanoke, Va., where he teaches at Hollins University. (One of the new fleet of America’s global writers, Barkan grew up in Africa, France and India, studying at Yale and teaching in Japan.)

Everyone learns to deal with sudden violence by immediate compliance and acceptance of humiliation. A gay Mexican national who works for a company called U.S. Wheat is beaten viciously on one of the city’s elevated freeways. In Mexico, he warns, “You have to pretend you don’t hear or see things because if you do the whole world will come crashing in on you like a tidal wave.”

Barkan works without the deceptions of 21st century cerebral irony. Behind the scenes lies a sophisticated intelligence that yields to a sense of humanity. The author identifies closely with the suffering of his characters, like a retired nurse from Cleveland in “I Want to Live,” who moves to Mexico to escape the high cost of living in the States only to face the possibility of a double mastectomy.

In 1950, the poet Octavio Paz wrote that North Americans “love their fairy tales and detective stories and we love myths and legends.” Sometimes Barkan allows a bit of the cosmic to intrude, as when a painting professor, who is slipping into dementia, finds himself on top of the highest pyramid in Mexico “(asking) for forgiveness from the heavens.”

There are other numinous moments, even in the face of near certain death. A conceptual artist is abducted by “trapezoidal thugs” and later dumped in the street. Wild dogs rip the sack from his head, and he sees “the burning lights of a mercury street lamp shining like in a concentration camp, a small star in the sky in the infinite beauty and depth of the universe almost hidden behind.”

“Mexico” was completed before Trump’s infamous call for quasi-war. (“I think your military is scared. Our military isn’t, so I just might send them down to take care of it.”) Those who insult Mexico’s dignity should recall Gen. “Black Jack” Pershing’s candid assessment of his failed campaign to capture Pancho Villa a century ago: “Having dashed into Mexico with the intention of eating the Mexicans raw, we turned back at the first repulse and are now sneaking home under cover like a whipped curr with its tail between its legs.”

But, of course, America already has an armed presence in Mexico, which is affirmed in “The Sharpshooter,” a military yarn about a dyslexic CIA/DEA sniper named Jeremiah who is involved in a bungled sting on the Sosa cocaine cartel.

Jeremiah may suffer from minimized empathy — he has 39 kills — but, when he returns home to Wichita, disillusioned, he delivers a jarring soliloquy on the futility of America’s drug war: “the liquid train of drugs will forever come into the country as long as people want to party, as long as people are sad, as long as people feel they have nowhere to turn in their hour of need, when God and Jesus and nothing above will seem to quiet the pain within.”

Against today’s talk about mass deportations and internment camps, the book counters with a more hopeful coda, “The Escape from Mexico.” A teenage refugee from gang warfare flees to Florida in 1983 and makes his way through the American immigration system. Thirty years later, a successful orchestral bassist, he meditates on the scar from an old knife wound while bowing in the interludes that “Beethoven gives a bass player to remind the audience that sorrow is the underlying note of a life as it seeks higher ground.” Such powerful epiphanies are the treasures buried within “Mexico.”

FICTION

‘Mexico’

By Josh Barkan

Hogarth/Crown

256 pages; $