He’s a star preacher on the Pentecostal circuit, “burning through all the churches round these parts” and “praying like a fever let loose.” So what makes Asher Sharp change? To be sure, he’s grown skeptical of prayer, not the godliest of conditions for a pastor at the Cumberland Valley Church of Life in rural Tennessee.

There’s his wife, Lydia, from whom he’s increasingly estranged. Praying constantly, “numbed by the church,” she frets that Justin, the couple’s 9-year-old son, is too “tenderhearted,” which is precisely the quality that Asher cherishes in Justin, whom he’s trying to save from Lydia’s scriptural brainwashing.

Then there’s the Holy Ghost-sized guilt Asher has been carrying for 10 years, since he shunned his gay older brother, Luke. Luke has disappeared, though Asher suspects he’s probably down in Key West. On occasion, unsigned picture postcards arrive from Florida. Scrawled across the most recent is a quotation from Thomas Merton, the late Kentucky author and monk: “Everything that is, is holy.”

Reading Merton's books, Asher develops a benevolence at odds with the "mean-hearted" religiosity of his wife and her tongue-speaking allies in the Church of Life congregation. Such is the division within today's evangelical Christianity, the subject of "Southernmost," Silas House's sixth novel, in which a dispute over the acceptance of homosexuality leads to tragic consequences.

“Southernmost” opens with a torrential flood that will trigger Asher’s final break with his church’s rigid martinets. Some folks in the area believe the Supreme Court’s recent ruling on same-sex marriage triggered the natural disaster. But to Asher, the tempest becomes a different sort of omen.

His gay neighbors, Jimmy and Stephen, lose their house in the flood. Nevertheless, at significant personal risk, Jimmy leaps into the maelstrom and rescues a Church of Life deacon and his daughter.

In the aftermath, when the two begin attending services, the Church of Life board demands Pastor Sharp expel the outsiders immediately. During his sermon, overcoming his natural cowardice, Asher shouts, “We’ve got to quit this judgment!” A film of the outburst makes it to YouTube, and, subsequently, he’s either hailed as a folk-hero or reviled as a “queer-lover.”

In “The Origin of Others” (2017), Nobel Laureate Toni Morrison elaborates on the process of “inventing the other;” the outsider; the stranger. “The danger of sympathizing with the stranger,” she writes, “is the possibility of becoming a stranger.”

This is, of course, what happens in “Southernmost,” when Asher Sharp embraces Jimmy and Stephen into the fold. Asher’s position at the church is quickly usurped by the deacon whose life Jimmy saved, and, during the inevitable divorce proceedings, in which Lydia introduces the now infamous video, the court denies Asher shared custody of his son.

This agonizing turn of events becomes unbearable for Asher. He nabs Justin and heads south in his Jeep Wrangler. Skirting Atlanta, they flee through the silent countryside, to the Keys, where they come across an “old railroad bridge, stretching out like a concrete mystery.”

With Key West’s cool rains that come “from some place not of this earth,” Asher feels “as if they are in a different country.” Only they’re not, so he’s constantly looking over his shoulder for the cops.

Asher intends to hunt for Luke, although Key West’s tropical lethargy and his fugitive lifestyle create impediments to motivation. Understandably, a tension surfaces between father and son: Justin feels like he’s been made a prisoner, which he has. But Asher’s fear that Lydia’s fanaticism would have made Justin miss “the wonder of everything” proves to have been a needless concern.

Justin is a smart kid who moves into the foreground as the most compelling character in “Southernmost.” Like his dad, he longs for the trees and rivers of their Tennessee shire. He believes in “The Everything,” which resembles the pantheistic nature worship of Thoreau and Coleridge.

Silas House is an award-winning author and distinguished academician; he's a sincere, woodsy chap, carpenter-like. It's not hard to imagine shavings curling up around him as he chips away at the new novel, attacking the inessential with a reasonably priced plane, leaving bumps and knobs here and there. Glimmers of flourish break through the well-measured narrative: "cicada's songs shook like nervous tambourines." Florida's horizon explodes with "the red of a geranium" and, squeezing it a little, "The sky is the pink of grapefruit meat."

To his credit as a true novelist, House writes with understanding, even sympathy of sorts, for the intolerance on display in the early stretches of “Southernmost.” This cannot have been an easy task. “The characters I’m not like are the ones I worked hardest at,” he confided during a June appearance at Atlanta’s Wrecking Bar.

His recent life experience has been rich with irony. When he came out as gay a few years ago, he said he was “surprised by the number of conservatives who accepted me … and [that] people who were open-minded were not as open-minded as I thought they would be.”

As “Southernmost” concludes, Asher Sharp declares that, like a good Tennessee boy, he still believes in the law, even if it’s sometimes mistaken. Unlike certain political figures who justify as “biblical” the forced separation of children from their parents at the Mexican border, Asher knows from the outset that kidnapping Justin was wrong, even if his intentions were right. He wants his brethren to stop judging, but in the end he’ll escape neither judgment nor justice when he returns home with his son.

The restoration of family bonds is an important theme running through House’s work. We know that Asher will be reunited with Luke, but what will be the extent of his brother’s forgiveness? As for Justin and his parents, things play out the way you think they might, only not exactly, which is just the way they always do.

FICTION

‘Southernmost’

By Silas House

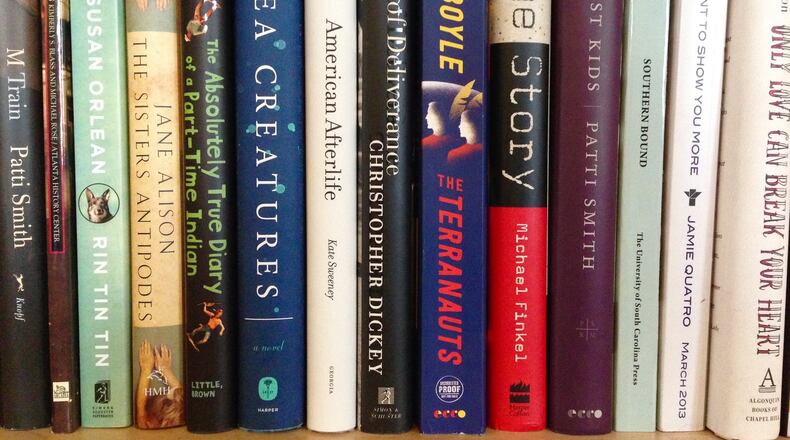

Algonquin Books

352 pages; $26.95

About the Author

Keep Reading

The Latest

Featured