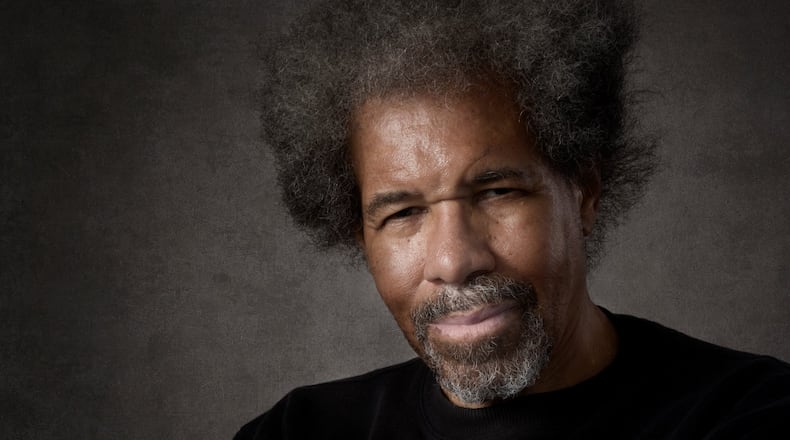

In his lockdown memoir, "Solitary," Albert Woodfox laments, "At one time my greatest dream was to go to Angola prison. Maybe that's all I'd been allowed to dream." A wayward teenager from New Orleans, Woodfox's Angola dream became a hellish nightmare soon enough: 40 years in solitary confinement, longer than any prisoner in American history, for a murder he didn't commit.

Today, Woodfox, 72, is a free man. Following decades of crushing isolation, serial torture and rigged trials, he’s exempt from bitterness, though still full of pluck. An unsubdued Black Panther, he holds tight to the organization’s political creed and code of behavior that became his life-saving motivational mantra.

During his adolescence, Woodfox stole pastries and ran streetwise confidence games. In 1965, when he turned 18, he was arrested for auto theft. He opted for his first stretch in the Louisiana State Penitentiary at Angola. Paroled, he stumbled into an armed robbery fiasco at a joint called Tony’s Green Room, for which he was sentenced to 50 years.

Woodfox is forthcoming and remorseful about this sordid part of his biography. “Writing about this time of my life is very difficult,” he admits. “I stole from people who had almost nothing. My people. Black people.”

The Panthers’ legacy has taken a hit in recent years, with some of its original leadership implicated in murder and deeds most foul. But for Woodfox, after a short-lived escape to Manhattan where he landed in the Tombs municipal jail, his encounter with the so-called “Panther 21” changed the course of his life overnight.

“They taught me my first steps,” he recalls. “They acted like they weren’t even in prison … It was as if a light went on in a room inside me that I hadn’t known existed.” He embraced the Panther platform that emphasized honesty and sobriety. “In the past, I had done wrong. Now I would do right. I would never be a criminal again.”

Upon his return to Angola in 1971, Woodfox made it his mission to educate and organize the prison population. “I turned my cell into a university,” he writes. His reading list included books by Malcolm X, Shakespeare and Louis L’Amour, which he shared with others on his tier.

Spanning 18,000 acres of hell, Angola had been the site of an antebellum “slave-breeding plantation.” In 1901, it became Louisiana’s maximum-security prison farm. At the time of Woodfox’s arrival, cotton picking and sugarcane cutting were common to the prison economy. Violence was random, irrational.

“At Angola men would stab each other over a game of dominoes.” “Shot callers” and “rape artists” lurked at every turn. In Woodfox’s description, “Sexual slavery was the culture at Angola.”

Woodfox and his comrades, Herman Wallace and Robert King (later known as the Angola 3), pushed back on two fronts: They sought to protect the more vulnerable inmates from predators, and they challenged Angola’s sadistic official regime, e.g., the savage beatings of prisoners held in restraints and degrading strip searches in which men were treated as “livestock.”

The critical moment arrived in 1972 with the murder of a young Angola prison guard named Brent Miller, who was stabbed multiple times. Woodfox, Wallace and others were set up by prison authorities to take the fall. The prosecutors, judge and homogeneous jury had suspicious, winking relationships. None of the three eyewitnesses against Woodfox could get their stories straight. One was nearly blind, and another was bribed by Woodfox’s arch foe, warden C. Murray Henderson. In Woodfox’s forensic summary, “There was a clear, identifiable bloody fingerprint that didn’t match me,” or any of his co-defendants. The Associated Press piled on with the headline: “Militants Said Cause of Death, ‘Black Power’ Backers Blamed at Angola.”

Beyond the bogus homicide charge, it’s hard to imagine how an inmate reading Ho Chi Minh and Dickens could have been all that dangerous to the general Angola population, even with his demand for an end to police brutality, but Woodfox was sentenced to 40 years in solitary confinement, or Closed Cell Restricted.

Prisoners were locked down 23 hours a day, sometimes fed off the floor, denied water and gassed. Yes, they would resist, sometimes forcefully. On other occasions, they organized hunger strikes. “We wanted the other prisoners to see that our struggle for dignity was more important than our own safety and our own freedom and our own lives,” Woodfox writes. His universe became a six-by-nine cell contracting in claustrophobia. His health deteriorated with high blood pressure, diabetes and Hepatitis C.

Amazingly, many heroic figures materialize just as the Angola 3 are nearly forgotten, including the pro bono legal eagles who crash head-on into the state’s shrubbery of writs and re-writs, diverting prosecutorial shams. Most striking, though, is Teenie Rogers, who believed for much of her adult life that Woodfox was guilty of killing her husband, Brent Miller, until she didn’t anymore.

“Solitary” would have been enhanced with photographs and a detailed map of the Angola prison grounds, not to mention a small chart illustrating the Pelican State’s arcane judicial system: nine rings with a frozen lake at the bottom.

Gore Vidal once wrote, “If man is to survive in a non-human universe of which he is a trifling part, the idea of justice must be maintained, for without justice there is chaos.” There’s plenty of chaos in “Solitary,” but, when it counts, there’s just enough justice for Albert Woodfox to have the last word.

NONFICTION

by Albert Woodfox

Grove Atlantic

433 pages, $26

About the Author

Keep Reading

The Latest

Featured