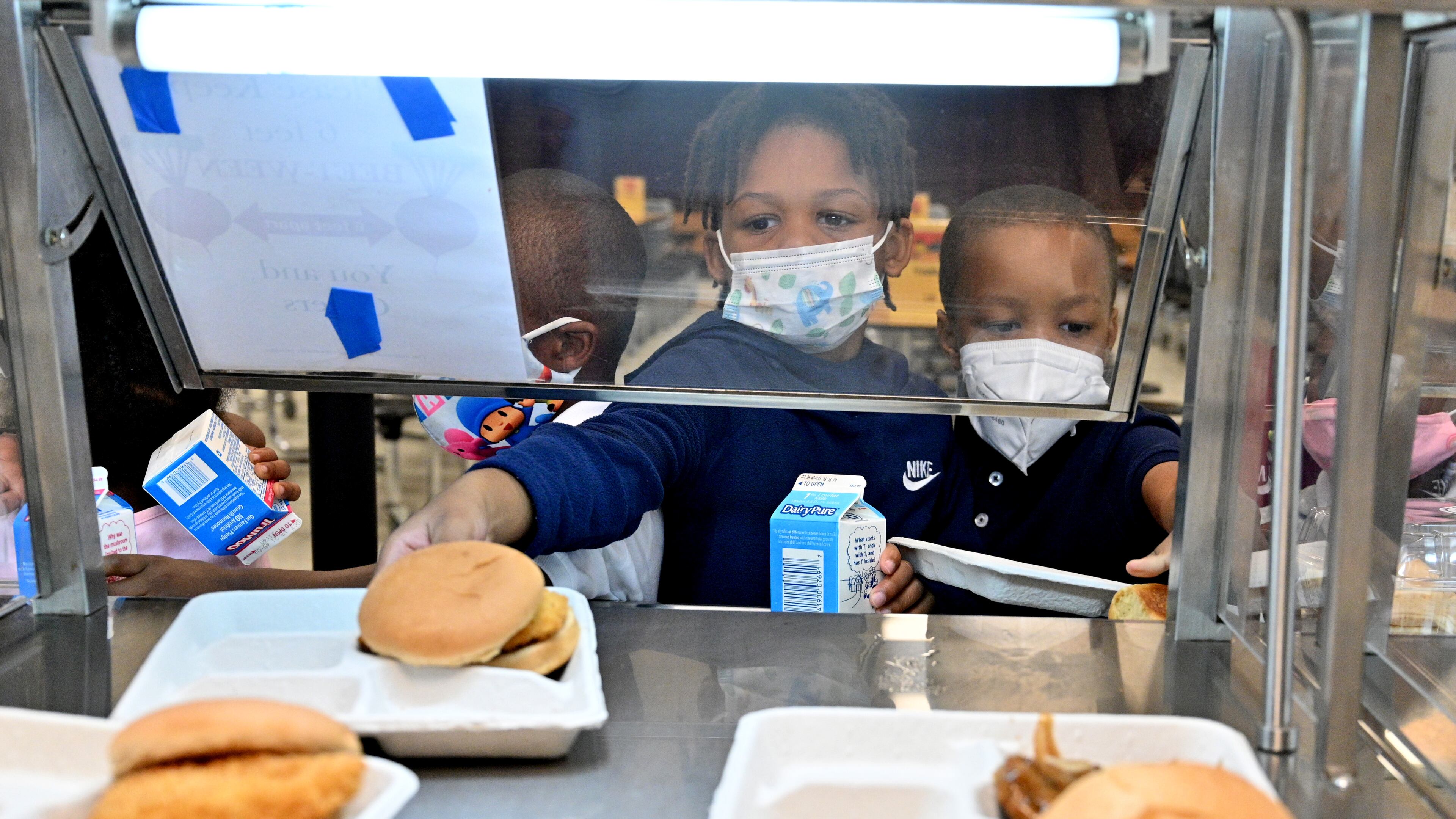

Metro Atlanta schools adjust lunch amid food supply, staffing problems

National food supply shortages and staffing challenges are making it harder for metro Atlanta schools to serve meals to students.

Faced with fewer pizza options and scarcity of French toast sticks, school cafeterias have had to rework breakfast and lunch menus, dish up different or limited entrees and adjust meal times. Many schools are doing so while serving more students with fewer workers.

Schools say they’ve been able to feed all students and that children aren’t going hungry. But the troubles have strained food service departments, and it’s unknown how long it will take to recover from supply chain problems.

”I’m optimistic, but I will say … the manufacturers have told me that it will get worse before it gets better,” said Alyssia Wright, executive director of school nutrition for Fulton County Schools. “We are still here taking care of their kids, making sure that they have healthy foods available.”

Fulton is Georgia’s fourth-largest district with an annual nutrition budget of more than $40 million. The district, like others, received federal waivers to provide meals at no cost to all students this year, regardless of income level.

That means schools have more bellies to feed.

In August and September, Fulton served 719,210 breakfasts and more than 1.6 million lunches, up 6% and 13% respectively from pre-pandemic numbers in the fall of 2019.

Further complicating the situation, food manufacturers are operating at a lower capacity and there’s a dearth of truck drivers and warehouse workers, said Jacqueline Vernarelli, an associate professor and public health nutritionist at Sacred Heart University in Connecticut.

Wright said distributors and manufacturers dialed down their product supply when children across the country were learning virtually. As this school year approached, companies were unsure of how much food schools would need.

Fulton has had to get creative.

When her schools could no longer order their popular shrimp poppers, they switched to crispy cod nuggets. They’re trying a cinnamon toast crunch bread at breakfast and pizza quesadillas in place of other foods. Wright said they introduced new produce, such as plums and tangerines.

Clayton County Public Schools felt the supply crunch shortly after classes began in early August and limited students to one breakfast and lunch entrée. Problems have persisted through the fall, although the district has been able to offer salad options to accompany the main meal.

Gwinnett, DeKalb and Atlanta school systems also have had to improvise.

If a Gwinnett school can’t get chicken nuggets, for example, they’ll find an alternative, said district spokesman Bernard Watson. He added: “our school cafeterias have not run out of food and will always have food options available.”

The food-service vendor contracted by Atlanta Public Schools said it’s working with suppliers to prioritize deliveries to schools. Southwest Foodservice Excellence, or SFE, said it’s “seen a marked improvement week over week in product availability.”

When a Cobb County school couldn’t get meal trays, they cut salad containers in half and used each side as a makeshift tray.

Districts have had to confront staffing shortages too.

Fulton is offering a $1,000 signing bonus and pay that starts at $12.18 an hour. Schools are sharing staff, and the central office nutrition team is also lending a hand, Wright said.

The DeKalb district is reassigning employees to sites where they’re most needed.

In Atlanta, the union that represents school food-service workers typically has about 300 members. That number is down to about 180-200, said Humeta Embry, executive director of the American Federation of State, County and Municipal Employees Local 1644.

She said problems pre-date the pandemic, though that has exacerbated the issues.

Bus drivers are helping out in cafeterias in between their morning and afternoon routes. SFE, the district’s vendor, tapped an employment agency to recruit full-time workers, APS said in a statement.

SFE said “motivating, supporting, and retaining staff is both a problem and a priority.” In a statement, the company said staffing levels are improving “each week.”

Embry called for APS, one of the few districts to outsource its food-service operation, to move it back in-house. She said workers need more help and better pay.

“They’ve overworked. They’re quite exhausted,” she said. “It puts a level of stress and burden on them that they haven’t seen before.”

Reporter Leon Stafford contributed to this article.