The story had been floating around in author Stephen Carter’s head for a long time.

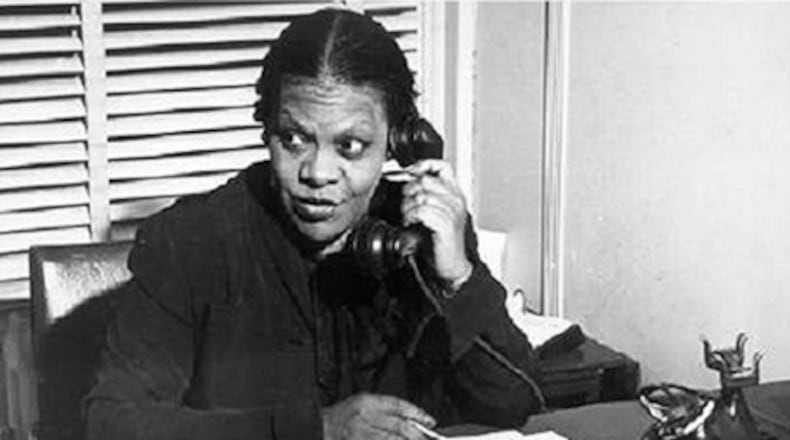

A black woman born in Atlanta at the turn of the century who went off to Smith College and Fordham University law school. She was later appointed the first black woman assistant district attorney in New York for a team that would take down Charles “Lucky” Luciano, the Italian-born mobster considered to be the father of organized crime.

That woman, Eunice Hunton Carter, was Stephen Carter’s grandmother. As a child, he knew very little about her illustrious career and everything about her imposing presence.

“When she was alive she was this huge intimidating figure in my life and the lives of my four siblings who was always correcting our grammar or our use of the wrong fork at the dinner table. When she died I began to hear these stories,” said Carter.

Carter shares those stories in his new book “Invisible,” (Henry Holt, $30). On Nov. 13, he will appear at the Atlanta History Center for a lecture as part of the Center’s author program series.

A longtime law professor at Yale University, Carter is most well-known as a novelist, though he has also published eight works of non-fiction. With most of his books, he writes them and moves on to the next, he said, but “Invisible” continues to fascinate him.

“Usually when I write a book, I don’t want to talk about the book. This one I love talking about because Eunice’s story is so inspiring and I am really grateful to have the opportunity to tell her story,” Carter said.

Eunice Carter was born in Atlanta in 1899. Her parents had recently moved from Virginia but just a few years later fled the city in the aftermath of the 1906 riots that sent much of Atlanta’s black middle class running off to points north. The family landed in Brooklyn where Eunice would set off on the path to fulfill her childhood dream of becoming a lawyer. She earned bachelor’s and master’s degrees from Smith College in four years and a law degree from Fordham University in 1932.

In Harlem during the renaissance years, Eunice quickly made a name for herself as a writer and ascended the ladder of the black elite. She was married to a prominent dentist with whom she had a son. She also had loads of ambition.

A run for a seat in the state legislature and her early attempts at launching her own law firm were not successful but in 1935 special prosecutor Thomas Dewey, the future governor of New York and future presidential candidate, appointed Eunice to a team of lawyers charged with taking down the mob.

Newspapers around the country ran headlines about the only black and the only woman to be appointed. “She was a celebrity just for being hired. It was something I hadn’t fully appreciated,” Carter said.

The family lore that had been shared about Eunice was mostly accurate, Carter said. But during the four years that he and his daughter, Leah, spent researching the book, there were many things about Eunice that surprised him.

He discovered the remarkable accomplishments and sacrifices of her parents and how hard it was for Eunice to navigate black high society in Harlem.

“I hadn’t really appreciated how difficult that climb toward the top of Harlem society was and how tenuous the hold on that pyramid could be and that (Eunice) was able to balance those things,” he said.

He learned from his father that Eunice was a key figure in the famous trial against Lucky Luciano. In the book, Carter offers the details of how Eunice was relegated to handling vice cases that Dewey deemed unimportant yet she managed to cobble together the only strategy that could link Luciano to an actual crime with real evidence. In 1936 the case went to trial with Eunice sitting in the wings with the other spectators instead of at the table in the front of the courtroom with her fellow attorneys. She must have been miffed given all the effort she had put into the case but she never appeared ruffled.

“She hardly ever in her life complained about being mistreated. She was going to make the most of whatever opportunity she had. She was not backward looking at all. She was always deciding what to do next,” Carter said. “She could not have accomplished some of the things she accomplished…if she had been a person who was worried about what had been done to her by this person in the past.”

But for all of her professional successes, Eunice suffered personal challenges. Her relationships were often strained. “I am not sure she had close friends but she had a wide circle of acquaintances,” Carter said. Those individuals included Eleanor Roosevelt, Mary McLeod Bethune, and Mary White Ovington. And certainly she was close to her mentor, Dewey, for whom she campaigned throughout his political career.

Driven as she was by ambition, Eunice grew bitter when she didn’t get the things she aimed for, most notably becoming a judge. Eunice blamed her younger brother for standing in her way. “He was a big communist and a very dedicated one and that had to have hurt her,” Carter said. The siblings stopped speaking and the rift between them would never be bridged.

Eunice died in 1970 when her grandson was in high school and while her full story wasn’t revealed to him until after her death, it continues to leave an impact.

“It is a story I know I can never live up to. Whatever I may do in life – which is fine – I am never going to be the kind of figure she was,” Carter said. “It is nice to look back and look at these really great things. It makes me hopeful about the future.”

EVENT DETAILS

Atlanta History Center Author Program Series Presents: Stephen Carter, “Invisible” $10. 7 p.m., Nov. 13., Margaret Mitchell House, 979 Crescent Avenue NE, Atlanta

About the Author

Keep Reading

The Latest

Featured