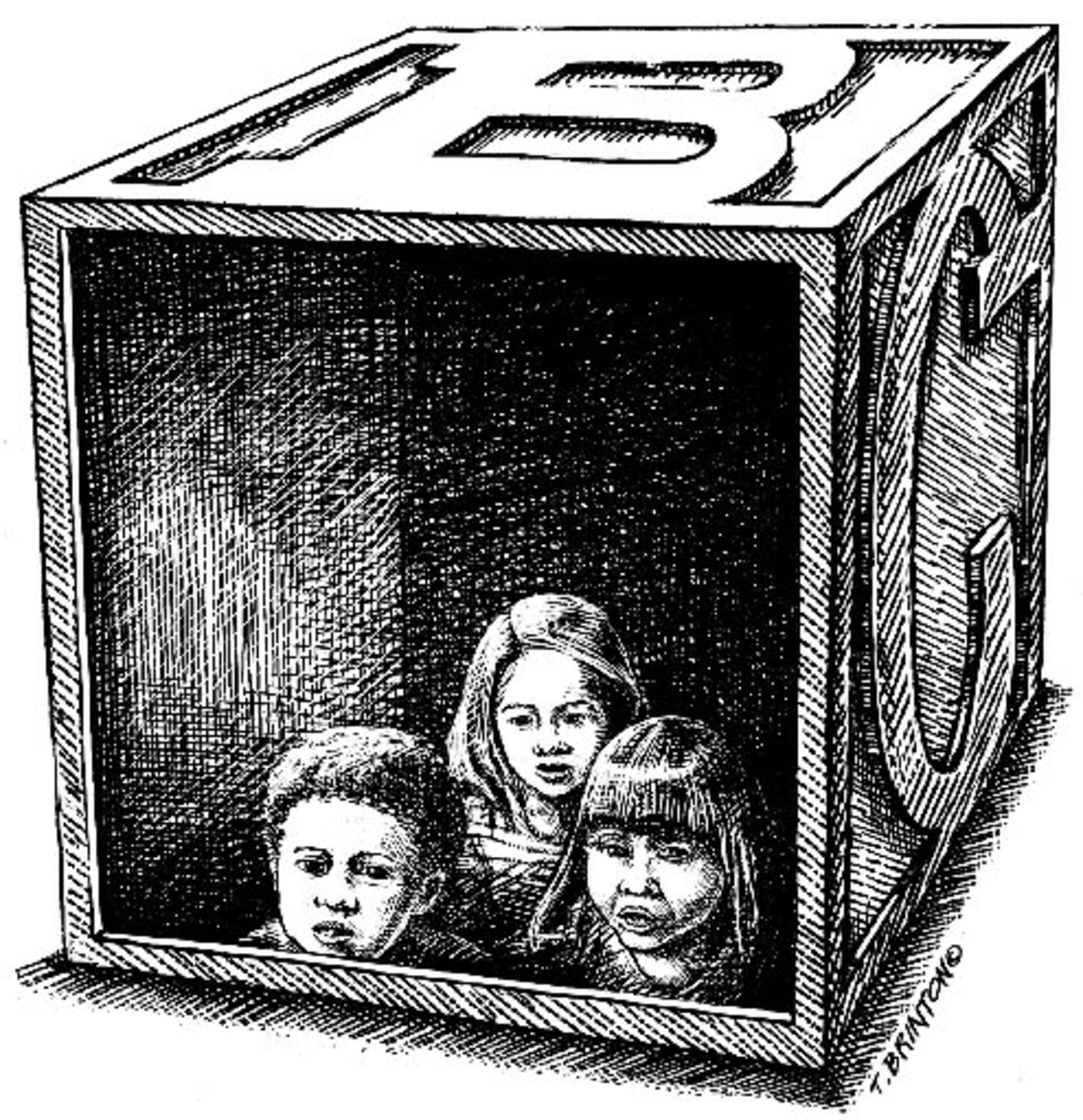

Report on chronic absences: Kindergartners miss as much school as middle schoolers

A report released tonight shows chronic absences – viewed typically as a problem in middle and high school – occur even in kindergarten.

The report, "Mapping the Early Attendance Gap: Charting a Course for Student Success," calls for more investigation into children who miss 10 percent or more of school a year, the causes of those absences and possible remedies.

“It really is something that affects our youngest children," said Hedy Chang, director of Attendance Works and an author of the report, in a media call this afternoon. “And many of these are excused, not unexcused absences.”

A lot of children miss school for chronic health problems, such as asthma, obesity and diabetes. Among American students, asthma is the leading cause of absenteeism.

(I ran an excellent essay a few days ago by a UGA professor emeritus on this same issue. )

These chronic absences are being masked because schools report daily average attendance, said Chang.

While valuable for schools to know how many students show up on average each day, a daily tally conceals the number of students missing so much school they are at risk for academic failure.

Research shows missing 10 percent of the school year -- 18 days to 20 days -- undermines learning, said Chang.

Most policy discussions center on countering unexcused absences and truancy, both of which represent serious problems. But schools cannot afford to overlook students with high numbers of excused absences as they, too, suffer academically, said Chang.

On the media call, Chang and Rochelle Davis, president and CEO of Healthy Schools Campaign, emphasized that while schools ought to collect the data on chronic absences, they cannot solve the problem alone; the greater community has to be part of the solution.

For example, asthma in children has been linked to environmental factors including outdoor air quality, which schools cannot address on their own. A family's ability to control a child's asthma depends on access to affordable health care, which also entails a larger community response.

Chang and Davis noted schools can promote student health by improving indoor air quality, employing a school nurse and providing screenings, nutritional foods and daily exercise. Parents also have to be reassured their child's medical needs can be met in the school setting.

For example, parents may keep an asthmatic child home as a precaution, said Chang, explaining, "It is not always whether the asthma is debilitating, but whether or not the parent is comfortable with what can happen at school to address it."

"Health and wellness should be incorporated in every aspect of school experience," said Davis on the media call. "They need to be in school in order to learn. When health prevents them from being in school that is obviously a problem. The problems of chronic diseases, asthma, obesity and diabetes, have doubled among children over the past several decades and behavioral health issues continue to be a problem."

While both women cited the oft-quoted estimate that one out of 10 students is chronically absent, there is no reliable nationwide data. That will change in the spring when the federal government releases a long-awaited count of chronic absenteeism in U.S. schools.

Here is the official release on the report:

Disparities in school attendance rates starting as early as preschool and kindergarten are contributing to achievement gaps and high school dropout rates across the country, according to a new report released today by Attendance Works and Healthy Schools Campaign.

"Mapping the Early Attendance Gap: Charting a Course for Student Success" documents that absenteeism, while a concern for all students, disproportionately affects low-income children, students from certain racial and ethnic groups and those with disabilities.

Moreover, many of these absences do not involve truancy or skipping school; rather, the absences are excused and tied directly to health factors such as asthma and dental problems, learning disabilities and mental health issues related to trauma and community violence.

"These early attendance gaps can turn into achievement gaps, which contribute to our graduation gaps," said Hedy Chang, director of Attendance Works and an author of the report.

"It's not enough to say we have an absenteeism problem. We need to know who is missing too much school, when and where absences are mostly likely to occur and why students are chronically absent. This information is essential to targeting the right resources so we turn around poor attendance, especially for the students most at risk."

The report, released at the start of Attendance Awareness Month, maps the nation's attendance gaps using available research, including a state-by-state analysis of testing data from the National Assessment of Educational Progress given in 2011 and 2013. It builds on 2014 research by Attendance Works that showed students who miss more school than their peers consistently score lower on standardized tests.

Key findings in today's report include:

The youngest students - those in preschool and kindergarten - have absenteeism rates nearly as high as teenagers. While poor attendance is often seen as a problem in middle and high school, research shows that it is also an issue in the early grades. State reports show, for instance, that in Rhode Island, 16 percent of kindergarten students missed too much school compared to 17 percent of 8th graders and 22 percent of 9th graders. In Utah, the kindergarten rate of 16 percent was higher than that in 8th or 9th grade. Research show that these missed days in the early years can lead to weaker reading skills, higher rates of retention and lower graduation rates.

Health concerns - physical and mental - cause many of the absences in the early grades. Asthma is a leading cause of absenteeism at all ages, accounting for 14 million missed days nationwide, health studies show. Dental problems contribute 2 million more. Absences due to depression, anxiety and oppositional defiant disorder are harder to quantify but rob many students of valuable instructional time. Too many absences of any kind - excused, unexcused or disciplinary - can erode achievement.

Low-income students face an attendance gap that undermines achievement in every state. The analysis of 2011 and 2013 NAEP data shows that 23 percent of low-income fourth graders missed three or more days in the month prior to the test, compared to 17 percent of their peers. At the 8th grade level, the gap is 8 percentage points nationwide with much wider gaps in some states. Weak attendance often reflects the challenges that accompany poverty such as unstable housing, unreliable transportation and limited access to quality health care. For all students - rich or poor - higher absenteeism correlates with lower test scores.

Children of color have higher overall rates of absenteeism than white students. The NAEP figures, bolstered by state and local studies, show the highest rates nationwide among American Indian/Alaskan Native students. Black and Hispanic students typically have higher levels with some variations in localities and states. A deeper analysis can help schools and communities determine how much poverty, health considerations or ineffective school discipline practice is affecting attendance rates.

Students with disabilities are more likely to miss too much school than other students. The NAEP data show that students with disabilities are 25 to 40 percent more likely to have high rates of absenteeism than their peers. Some of these absences can be attributed to the health concerns of physically disabled students, but others occur because of inappropriate placements, bullying or school aversion that often affects learning-disabled children.

The report also highlights the power of states to tackle absenteeism by tapping key champions, using data to identify students and schools with high chronic absence rates, especially in the early grades, and learning from places that have improved attendance despite challenging conditions. It emphasizes how chronic early absence can be turned around when school districts and community agencies, especially health providers, work together to partner with families to get students to class every day.

"Student health issues, including physical and behavioral health, are a leading cause of student absenteeism," said Rochelle Davis, president and CEO of Healthy Schools Campaign. "Ensuring that students are able to go to school each day in a healthy environment and have access to health services is a key strategy for reducing absenteeism. Health providers and public health agencies can and should play an important role in working with schools to turn around poor attendance."

The release of the report comes as schools and communities across the country are marking September as Attendance. More than 50 national organizations and hundreds of local communities are planning activities, issuing proclamations and beginning to map their own attendance gaps.

"The national data can point toward the patterns but local and state leaders must find out what is happening in their communities, especially for our youngest students, in order to improve school attendance and with it, achievement," Chang said.