On the second Friday in November, the women of Pulaski State Prison gathered in the gym for a memorial service dedicated to inmates who had died earlier in the year. The service was conventional. The circumstances were not.

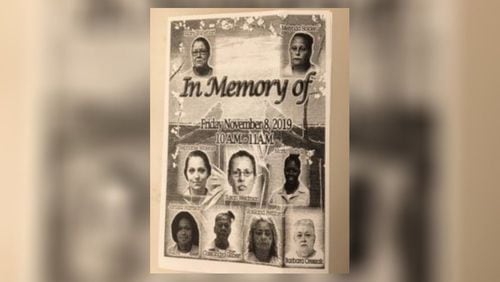

For the better part of an hour, the inmates sang hymns, recited the Lord’s Prayer and heard words of encouragement from the chaplain as they mourned so many fallen “sisters” that the photos filled the cover of the program.

Death has never been far from the surface this year at Pulaski, Georgia’s second largest women’s prison. Eight women have died there from cancer and other medical conditions in the past 10 months, and the deaths have struck a particularly troubling chord.

» PREVIOUSLY: Backlog of Ga. prison medical requests may put inmates' health at risk

Only four years ago, revelations of deaths due to negligence at Pulaski led to the dismissal of its medical director, Dr. Yvon Nazaire, and a state report focused on improving healthcare for women in the prison system. Now, with yet another wave of deaths, new concerns have emerged, with at least one physician contending that she tried to warn state officials that a crisis was looming.

“I told them if they didn’t correct this stuff, they’d have a lot of girls who had cancer,” said Dr. Cheryl Young, an OB/GYN who served briefly as the women’s health specialist for the prison system, a position created after Nazaire’s firing. “I told them that, but they didn’t want to hear it, because they didn’t want to spend the money.”

» RELATED: Eight deaths in 10 months at Pulaski State Prison

The Atlanta Journal-Constitution, examining the latest deaths through interviews, medical records and other documents, found that some appear to have resulted from long-term illnesses or other medical conditions that ran their natural course. But the evidence in at least three cases points to failures that once again caused inmates to languish, at times painfully so, as their treatments were delayed or their symptoms misunderstood.

In a setting where Pap tests are supposed to be part of annual exams, an inmate incarcerated 18 years died from cervical cancer that went undetected until it had spread to other parts of her body. Another died from colon cancer that spread to her liver before anyone realized she was seriously ill. And yet another died from severe septic shock and multi-organ failure just weeks after she was returned to the prison while still dealing with complications from intestinal surgery

Shaken by these and other deaths, some inmates at the Hawkinsville facility asked during an October meeting with staff whether those incarcerated more than 10 years could be screened for various types of cancer. They were told such tests would only be done when symptoms warranted, according to the meeting minutes.

“We are all concerned,” said Bridgette Simpson, an Atlanta-based advocate for formerly incarcerated women who was once incarcerated herself at Pulaski. “We don’t know what’s causing what.”

A spokesperson for Georgia Correctional HealthCare, the branch of Augusta University that provides medical services for the Department of Corrections, said the agency has looked into the deaths this year at Pulaski through its mortality review process and not seen a particular connection.

"They played a really good game. They tried to pretend they really cared, but the reality is they let me go and never changed anything." —Dr. Cheryl Young, an OB/GYN who served briefly as the women's health specialist for the prison system

Responding to written questions from the AJC, the university’s associate vice president for communications, Christen Engel, also pointed out that 82 percent of the women at Pulaski have chronic illnesses, making it possible that multiple deaths can occur without suggesting problems in medical care.

“It is important to note that Pulaski houses the system’s most ill female inmates,” Engel wrote in an email.

Joan Heath, the director of public affairs for the Department of Corrections, did not respond to a similar list of questions.

Hired, then fired

The medical care at Pulaski, a medium security facility that houses nearly a third of the state's roughly 3,800 female inmates, came under scrutiny in 2015 after the AJC detailed how seven women had died under questionable circumstances during a nine-year period in which Nazaire served as the prison's medical director.

A former emergency room physician in New York, Nazaire was licensed to practice medicine in Georgia and hired for the prison job even though he was under sanction by the New York medical board for negligence in treating ER patients, including one who died.

A review by Georgia Correctional HealthCare in response to the AJC’s stories found that three of the inmates who died in Nazaire’s care received treatment that fell below community standards. It also stated that new policies were needed in several areas, including more attention to women’s health issues and better vetting of physicians working on temporary contracts.

But, in scrutinizing the current situation at Pulaski, the AJC found that some of the old issues still remain.

Young’s case raises particular questions. Hired in May 2016 to be the system’s women’s health specialist — a position created specifically to deal with the fallout from the Nazaire case — she was fired after just five months and never replaced.

Young’s personnel file contains only one document relating to her dismissal: a memo from Dr. Billy Nichols, GCHC’s statewide medical director, citing the doctor’s “failure to satisfactorily complete the provisional period.”

In a recent interview, Young said she spent weeks trying unsuccessfully to get Nichols and Dr. Sharon Lewis, the medical director for the Department of Corrections, to address several potential problems, including the prison system’s reliance on a far too limited standard for determining the possible presence of uterine cancer.

» RELATED: Women inmates suffer agonizing deaths

» FROM 2015: Georgia prison doctor fired for lying about work history

Then one day she reported to work at Pulaski and received a phone call from Nichols informing her that she wasn't a "fit" for the $235,000-a-year job, she said. "They played a really good game," she said. "They tried to pretend they really cared, but the reality is they let me go and never changed anything."

Engel wrote that there’s no evidence that Young warned Nichols of problems that were being ignored. She did not elaborate, nor did she respond to a request to make Nichols available for an interview.

Engel said Georgia Correctional HealthCare has contracted with gynecologists from outside the prison system since Young’s dismissal. Clinics run by those physicians are held once a week at Pulaski and the state’s other major women’s facility, Lee Arrendale State Prison, she said.

Vetting issues

The job of overseeing medical care at Pulaski has also been largely given over to physicians from outside the prison system, including one whose background indicates the state’s vetting process still has gaps.

Records show that Dr. Miguel Stubbs, an Austell internist, began working two days a week at Pulaski in November 2017 and continued into this year despite a history of lawsuits stemming from his oversight of nursing homes and long-term care facilities in the Atlanta area.

Stubbs was named as a defendant in six lawsuits filed between 2010 and 2015 alleging malpractice, wrongful death or negligence, including two in which the patients died after developing large and painful bedsores.

Although court records do not provide settlement details, Stubbs’ profile on the website of the Georgia Composite Medical Board in September listed four malpractice settlements ranging from $50,000 to $295,000.

Stubbs also was cited by the federal government in July 2017 for submitting 29 Medicare reimbursement claims for 10 people who were dead at the time. As a result of those claims, his Medicare billing privileges were revoked for three years.

Engel said Georgia Correctional HealthCare was aware of the four malpractice settlements listed on Stubbs’ board profile but didn’t know about the Medicare issue.

» DOCUMENT: Stubbs' citation by the federal government

She said the agency didn’t consider the lawsuits to be a problem because they were “successfully settled” and because they didn’t lead to disciplinary action by the medical board. As an added precaution, she said, Nichols personally reviewed the claims and concluded that they shouldn’t prevent Stubbs from working in a prison environment.

Stubbs told the AJC that no one from Georgia Correctional HealthCare ever questioned him about the lawsuits. He said he gave up the job at Pulaski in March only because the drive had become “taxing.”

Addressing the lawsuits, he said he got out of the long-term care business because he kept getting sued over “chart reviews” for patients who weren’t his daily responsibility. “Any chart in a nursing home, you pick one up, you’re going to find something wrong,” he said.

Stage IV

Marlo Nichols was serving a life sentence for felony murder stemming from a 1997 shooting outside an Atlanta nightclub when she died Sept. 21 in the Pulaski medical unit. The death certificate says the cause was Stage IV cervical cancer, leaving those who knew her to wonder: How? Why?

“I didn’t see anything like this,” said Nichols’ grandmother, Agnes Reid. “One time she called and told me she felt some knots or something in her stomach. And then the next thing I know she’s in the hospital.”

Credit: Family photo

Credit: Family photo

Nichols, 52, had in fact been making regular trips to the medical unit to complain about abdominal pain for about six months before it was decided in August that she needed to be examined at a hospital, according to Bertha Sullivan, another Pulaski inmate.

“She was going back and forth, back and forth, and they kept giving her Dulcolax,” Sullivan said.

During the hospital visit, tests revealed that Nichols had advanced cancer and that chemotherapy would do her no good, Sullivan said.

“I’m concerned, because when she got to the hospital in August, she was Stage IV,” Sullivan said. “What happened to Stage I, II and III?”

The American Cancer Society says cervical cancer can be prevented if a Pap test finds precancerous cells. The most invasive cancers are found in women who haven't had regular Pap tests, the organization says.

Credit: Jenni Girtman

Credit: Jenni Girtman

Women in the Georgia prison system are supposed to receive a Pap test and pelvic exam as part of an annual health assessment, according to a Department of Corrections policy in place since 2001.

Young said she couldn’t speak directly to Nichols’ situation, but she said she found that Pap tests weren’t being given as scheduled, particularly at Pulaski.

“They were so behind (at Pulaski) it was pathetic,” she said.

In pain and waiting

Cassandra Gilbert’s death played out along similar lines. In her case, complaints of abdominal pain were thought to be signs of a urinary tract infection until a tumor on her liver was discovered.

Emails written by Gilbert in her final days show in stark terms how the 55-year-old inmate from Fulton County, serving 20 years for racketeering, pimping and other offenses, saw her plight.

“I been complaining for a long time and they just been ignoring me,” she wrote to her daughter-in-law. “When they think you don’t have nobody they overlook you.”

A mass on Gilbert’s liver was first noticed in a scan last October during an examination by a urologist in Atlanta. The urologist, Dr. Thomas Schoborg, called the mass “suspicious” and wrote that a scan with better contrast was needed “as soon as possible.”

Credit: Family photo

Credit: Family photo

Records show that Stubbs immediately ordered a second scan, but it wasn’t done until late November. The second scan proved more conclusive, showing tumors in Gilbert’s colon, liver and lungs. Even so, the inmate still had to wait another two months before she was seen by an oncologist.

In a Jan. 9 email, Gilbert wrote: “They haven’t sent me to an oncologist yet and I have been waiting 4 months, every day the pain seems worse and worse.”

She died less than a month later at Navicent Health Medical Center in Macon, her treatment largely consisting of painkilling drugs.

Stubbs said he remembers Gilbert’s case as one in which security and other prison issues prevented timely care.

“In the Department of Corrections, things get done at a slower pace,” he said. “It’s just the way it’s set up with staffing, all those things you have no control over.”

`I’m sick again’

Stephanie Widener’s death in July came at the end of a downward spiral that began in February with complications from intestinal surgery, including a fistula that at one point caused the contents of her intestines to leak.

Watching the 39-year-old’s struggle has left some who knew her questioning whether those in charge of her care understood how sickly she’d become.

Credit: Georgia Department of Correction

Credit: Georgia Department of Correction

“Somebody failed her,” said Stephanie Taylor, a friend who lives near Widener’s family in Tunnel Hill. “From the (surgery) to the prison system, somebody dropped the ball, dropped it in a major way.”

Widener, who was serving a 30-year sentence for trafficking in methamphetamines, spent several difficult months after the surgery recovering at Helms Facility, a Department of Corrections institution in Atlanta largely reserved for pregnant females. She was deemed well enough to return to Pulaski in June, but it appeared to some who saw her that her condition was still dire.

“She was pale, her eyes were red, all her hair was gone,” said Jessica Jordan, who was then incarcerated at Pulaski and has since been released. “That wasn’t Stephanie.”

In an email to Taylor from Pulaski on June 25, Widener wrote: “Oh and btw I’m sick again. … I just feel so weak like when I first started walking again. … I can’t get better for some reason.”

On June 29, she was transported to WellStar Atlanta Medical Center after complaining of chest pain. She died there 10 days later due to what hospital records indicate was a multitude of problems, including an infection that had attacked her heart.

In September, Taylor and Widener’s half sister, Brandie, got matching tattoos on their forearms so they can remember the inmate and the ordeal that led to her death: “Too Beautiful for Earth.”

“Every time I look down at it, that’s what I think of,” Taylor said. “I don’t ever want to forget.”

Our reporting

Dozens of Georgia prisoners have died in recent years due to inadequate medical care, investigations by The Atlanta Journal-Constitution have found. Among the deaths, 11 men and one woman have died of diabetic ketoacisis after their diabetes wasn’t properly treated. In addition, at least a dozen women inmates have died after their diseases went undiagnosed or they failed to receive adequate treatment. AJC investigations also showed that the state has hired prison doctors with a history of medical mistakes and sanctions, and that at times prisoners have had to wait dangerously long periods because getting needed care.