The state of Georgia’s annotated version of state law cannot be protected under copyright law and sold for more than $400 a copy, the U.S. Supreme Court ruled Monday.

The decision resolves hotly disputed litigation between the state and public records activist Carl Malamud, who had published the code on his Public.Resource.org website. When Georgia insisted he take it down and he refused, the state filed suit and obtained an order from a federal judge directing him to remove it.

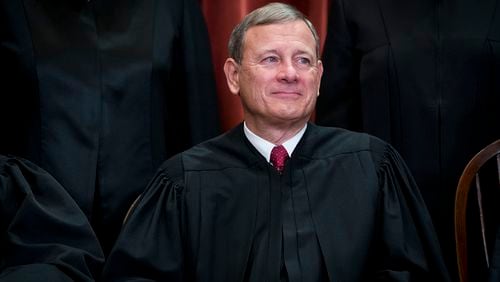

But the federal appeals court in Atlanta overturned that ruling, siding with Malamud, and the U.S. Supreme Court agreed in a 5-4 decision written by Chief Justice John Roberts.

The code at issue includes the text of every Georgia statute, as well as a set of annotations that appear beneath each provision. Those annotations typically include summaries of judicial opinions construing each provision, summaries of pertinent opinions of the state attorney general, and a list of related law review articles and other reference materials.

It is updated every year under the supervision of the 15-member Code Revision Commission, composed mostly of legislators. Under an agreement, LexisNexis has the right to publish the annotated code, and the data collection company charges $412 for a hard copy version.

The ruling turned on the court’s interpretation of the so-called government edicts doctrine. This originated from three cases the Supreme Court decided in the 1800s when it found that judicial decisions cannot receive copyright protection.

In those rulings, Roberts said, the court held that “officials empowered to speak with the force of law cannot be the authors of — and therefore cannot copyright — the works they create in the course of their official duties.”

With regard to Georgia’s code, the author of the annotations qualifies as a legislator, Roberts said. “Because Georgia’s annotations are authored by an arm of the Legislature in the course of its legislative duties, the government edicts doctrine puts them outside the reach of copyright protection.”

Roberts noted that LexisNexis publishes the non-annotated Georgia code — an “economy-class version” — online for free. In it, citizens can read statutes criminalizing broad categories of consensual sexual conduct, while “first-class readers” who buy the annotated version will see that those laws are “unenforceable relics that the Legislature has not bothered to narrow or repeal,” the chief justice said.

Roberts was joined by an unusual coalition of liberal and conservative justices: Sonia Sotomayor, Elena Kagan, Neil Gorsuch and Brett Kavanaugh.

In a statement, Malamud said he would offer Georgia any assistance he could to make the official code easier to use. “We’re very pleased with the court’s decision and are looking forward to the next steps, making the law more accessible to the people,” he said.

American Civil Liberties Union staff attorney Vera Eidelman called the ruling a victory for the First Amendment.

“No state should be able to charge individuals hundreds of dollars to see or talk about the laws that govern them,” she said. “The official work of judges and legislators rightly belongs to the public.”

Writing in dissent, Justice Clarence Thomas said the court’s ruling will come as “a shock” to 22 other states that rely on arrangements similar to Georgia’s to publish their annotated codes. “Perhaps, to the detriment of all, many states will stop producing annotated codes altogether,” he said.

About the Author