NASHVILLE, Tenn. — This was the heart of Saturday night, and honky-tonk singer-songwriter Whitey Morgan had Ryman Auditorium in an uproar.

Wearing a determined scowl and a long beard, Morgan prowled the stage as if looking for a fight. Now and again he’d let his band, the 78’s, carry the tune while he paused to pull on a bottle of whiskey.

“We’re settin’ here in the Mother Church,” Morgan said, gazing at the colorful Gothic windows at the back. “Come closer and sing with me.”

Down in front, hardcore fans raised their beers in salute. Up in the balcony, they were pounding on the oak pews and flinging fists at the ceiling.

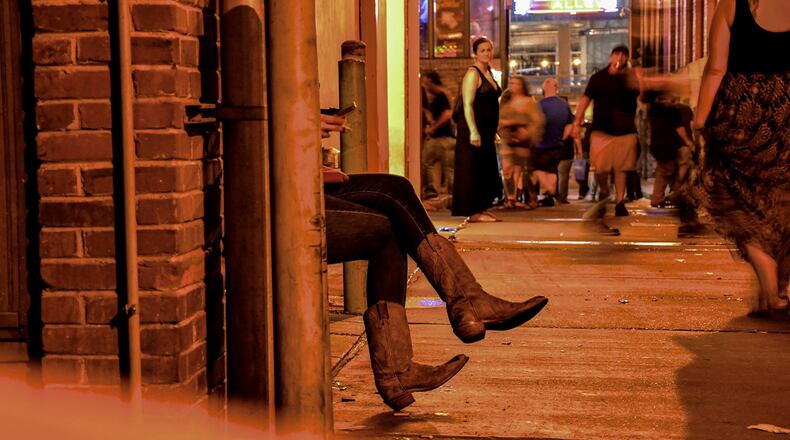

Just outside, Lower Broadway, a.k.a. the Honky Tonk Highway, was teeming with cover bands, club-hoppers and roving bachelorette parties. Two blocks south, Journey and Def Leppard had taken over the 20,000-seat Bridgestone Arena.

In the stadium across the Cumberland River, Taylor Swift was playing to a crowd of more than 50,000. And 11 miles northeast, Garth Brooks was headlining at the 4,400-seat Grand Ole Opry.

Nashville has music the way Willie Nelson has wrinkles. This city of 667,560 has grown so dramatically as a music industry hub, convention venue and tourist destination that if you went by the numbers, the Ryman’s 2,362 seats would make it a minor player.

But it isn’t.

The building went up in 1892. And although it has hosted orchestras, opera singers and distinguished speakers, the Ryman’s distinct character comes from being steeped in six generations of songs about whiskey, love, cars, joy, sorrow, farms, horses, mules, faithful dogs, faithless mates, mountains, hollows, wild flowers and lonesome train whistles.

It was home to the “Grand Ole Opry” radio show for more than 30 years. Now it hosts every stripe of country artist and a smattering of performers of just about every genre but rap.

On this stage, Bill Monroe and his band more or less created bluegrass music in 1945. One night in ‘49, Hank Williams won over the crowd so thoroughly that he was called back for six yodeling encores of “Lovesick Blues.” Johnny Cash first played here in 1956, was banned for bad behavior in 1965, returned to host a TV variety show in 1969-1971 and was mourned at a memorial in 2003.

Now it was Morgan’s turn at the Mother Church of Country Music. He brandished his guitar like a sidearm as he sang of lost souls, dead-end alleys, cocaine and old men who never gave a damn.

This was a honky-tonk crowd, more Harley-Davidson than Stetson, more T-shirt than western wear. When Morgan called them brother truckers — I’m pretty sure that was the phrase — they roared.

It was a fine moment, and if the people who built this hall weren’t already dead, it might have killed them.

———

MEET THOMAS RYMAN

A few days later in the lobby, tour guide Jonathan Brodeur took us back to the 1880s, when Nashville was about a tenth its current size.

Thomas Ryman was one of the city’s richest men, having built an empire of riverboats with plenty of boozing and gambling.

Then one day in May 1885, he stepped into a big tent where a traveling preacher, the Rev. Sam Jones, had gathered thousands of Nashvillians. Jones launched a tirade against sin, and by the time he was done, the riverboat magnate was ready to repent.

Before long, Jones persuaded Ryman to pay for much of a new building to be shared by local and traveling preachers — a tabernacle to celebrate Nashville’s newfound faith and probity.

The Gothic Revival landmark was to be built of brown brick with white trim around its tall, narrow windows. It would have a pulpit surrounded by curving wooden pews, seating thousands of worshipers. And it would stand just a block from the vice and revelry of Lower Broadway.

Years passed. Money ran low. By the time the tabernacle was completed in 1892, management needed to stage not only religious events but also secular programs, including lectures and music, to pay construction debts.

Before long, those secular shows began to reshape the space.

By 1897, the room had a new balcony, elegantly held aloft by several dozen slender steel columns, principally paid for by a Confederate veterans group. By 1901, the tabernacle’s pulpit had been supplanted by a stage, the better to present opera singers.

By 1914 Ryman and Jones were both dead, and the tabernacle had been renamed Ryman Auditorium. Scheduling was handled by a former bookkeeper named Lula C. Naff, who booked whatever acts might sell, including orchestras, the Imperial Russian Ballet, Booker T. Washington, Mae West, Helen Keller and W.C. Fields.

Meanwhile, throughout Appalachia, thousands of amateur fiddlers, guitarists, banjo and mandolin players had been mixing European and African instruments, taking church tunes into the world and creating a new sort of music, rural, vital and uniquely American.

Then in 1943, the music met the room. The “Grand Ole Opry” radio show, created in 1925 as a Saturday night celebration of country music and rural life, moved to the Ryman. Despite worries about rowdy crowds, Naff and “Opry” management agreed that the live broadcasts would fill the auditorium just about every Saturday night.

By the mid-1940s, comedian Minnie Pearl was a regular, hollering “Howdy!” and bringing homespun news from the half-fictional hamlet of Grinder’s Switch.

In 1954 Elvis Presley sang Bill Monroe’s “Blue Moon of Kentucky,” got a tepid response and never returned.

In 1957, three years after the U.S. Supreme Court ordered desegregation of the nation’s schools, Louis Armstrong played to a Ryman audience that was all white in the balcony, all black in the orchestra level.

In 1966, somebody decided that those tall, narrow windows could use some color and added red, yellow, green and blue tints, creating a stained-glass effect that made the space feel twice as ecclesiastical.

But even those who loved the Ryman had to admit that it was ungainly. No private dressing rooms. No air conditioning or elevators. And the surrounding neighborhood was getting seedy.

Mark Ribowsky, author of “Hank: The Short Life and Long Country Road of Hank Williams,” writes that “the hall was cramped and dirty, smelling of urine leaking from stuffed-up bathrooms and sweat.”

It got so bad, Ribowksy wrote, that Roy Acuff, a major Nashville power broker and member of the “Opry” since 1938, in 1971 called it a miserable place to perform and said, “I never want another note of music played in that building.”

And sure enough, in 1974 the “Opry” fled to a bigger, custom-built hall, 11 miles northeast of downtown — but first, workers cut out a circle from the Ryman stage to install at the new venue to signal continuity.

The Ryman Auditorium, apparently doomed, then languished for nearly 20 years.

———

‘AT THE RYMAN’

By the time Emmylou Harris and the Nash Ramblers recorded a live album there in 1991, the structure was so iffy that no one was allowed to sit on or beneath the balcony.

That left only about 200 usable seats, but Harris did three shows, savoring the chance to “feel the hillbilly dust” and dance on stage with 79-year-old Monroe. The resulting record and documentary, “At the Ryman” (1992), rallied public support for the rescue and restoration of the old hall.

In 1992 the building’s owner, now known as Ryman Hospitality Partners, announced plans for major renovations. In 1994 the auditorium reopened and a new era dawned.

Today the Ryman hosts about 200 shows a year, including visits from the “Grand Ole Opry” every winter and occasional church services and funerals. About 250,000 people a year book tours. The escorted version runs about 40 minutes, takes you through dressing rooms and onto the stage, and costs about $35.

And on stage, the story continues to unfold. In April 2017 Loretta Lynn marked her 85th birthday by performing a pair of sold-out Ryman shows.

Five months later, 23-year-old pop singer Harry Styles, formerly of One Direction, made his Ryman debut, telling the audience: “When we booked this tour, this was kind of the reason. This room.”

In August, as Whitey Morgan rollicked toward the end of his gig, he was just as reverent about the room but gruffer. He even bowed to history by covering favorites from Roger Miller and John Prine.

Then Morgan went back to his own lyrics, celebrating sinning, whiskey and just about everything that the Ryman’s builders wanted to wipe from this world. Behind him, the 78’s rocked ruggedly enough to offend any “Opry” purist.

In other words, the Ryman has been soiled. And saved. And my first night there was — cover your ears, Rev. Jones — a hell of a show.

IF YOU GO

Ryman Auditorium, 116 5th Ave. N., Nashville; (615) 889-3060, ryman.com. Ticket prices vary. Self-guided tours cost $21.95 for adults, $16.95 for kids 4-11. For guided tours, which cover more ground, the cost is $31.95 for adults, $26.95 for children ages 4-11.

WHERE TO STAY

Noelle, 200 4th Ave. N., Nashville; (615) 649-5000, noelle-nashville.com. This ultra-trendy downtown hotel, which opened in December, occupies a 1929 building. Three bars, one restaurant. Doubles from $629 a night.

Bobby Hotel, 230 4th Ave. N., Nashville; (615) 782-7100, bobbyhotel.com. This eclectic spot, which opened in May, has a lobby chandelier with tailfins and hub caps and a reconditioned 1956 Scenicruiser bus on its rooftop. Doubles from $350 a night.

WHERE TO EAT

Biscuit Love Gulch, 316 11th Ave. S., Nashville; biscuitlove.com. Often long lines on weekend mornings, but they move fast. Try the Chronic Bacon — thick, sweet and spicy. $4.

Merchants, 401 Broadway, Nashville; (615) 254-1892, merchantsrestaurant.com. Stately restaurant in an 1892 building. Its downstairs bistro gets busy but delivers solid food. There's a fancier menu in the dining room upstairs. Southern cuisine. Bistro sandwiches $12-$15, dinner main dishes mostly $22-$28.

Emmy Squared Pizza, 404 12th Ave. S., Nashville; (615) 248-2662, lat.ms/emmysquared. Tasty pizza in fancy flavors (and the pies are more rectangular than square). Pizza $13-$19, sandwiches $12-$19.

About the Author

Keep Reading

The Latest

Featured