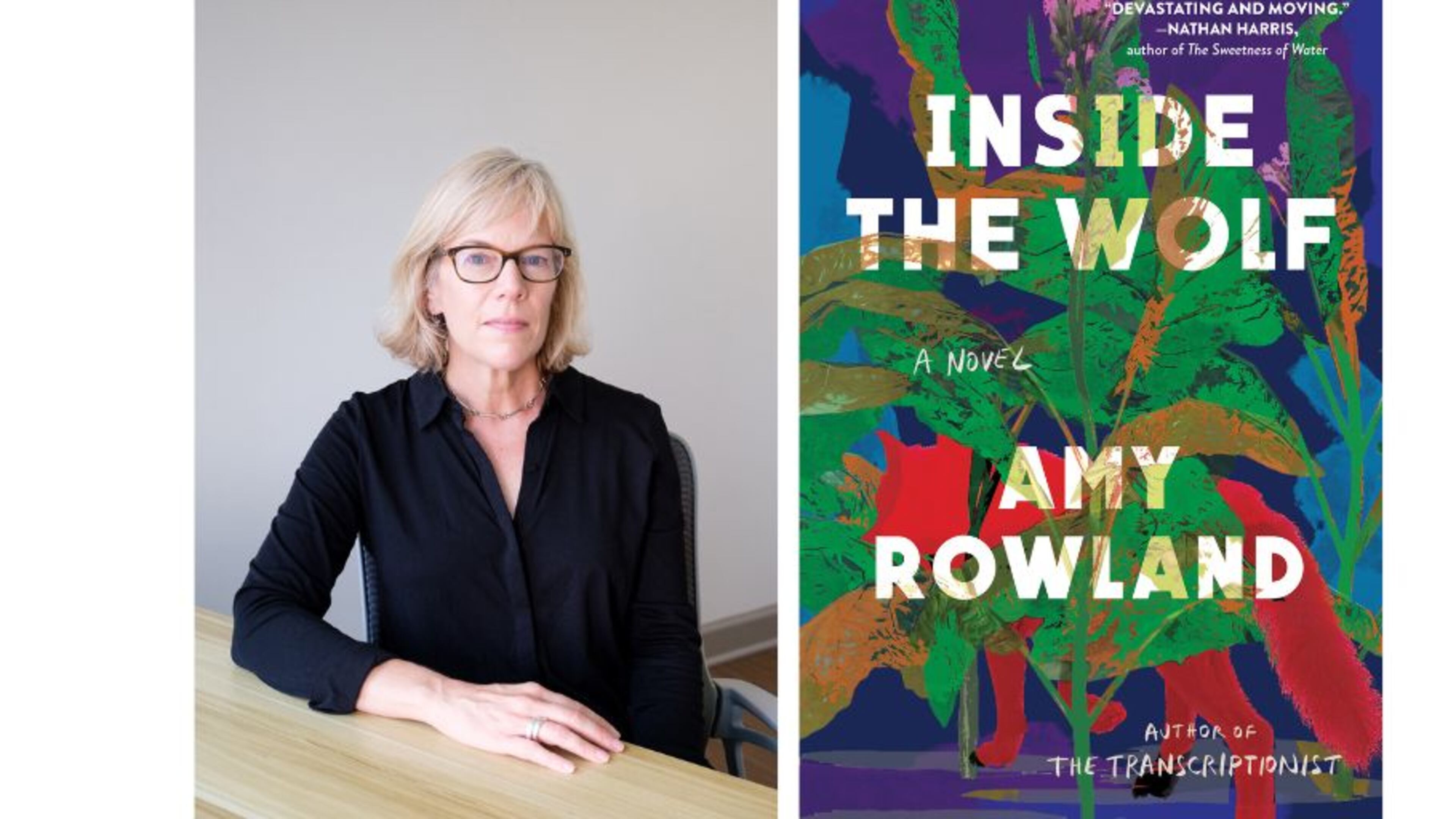

Displaced Southerner faces troubled past in ‘Inside the Wolf’

Firearm-related injuries became the leading cause of death for American children in 2020, according to the National Institute of Health. Author Amy Rowland addresses a harrowing subset of this national tragedy, child-on-child gun violence, in her probing work of Southern fiction “Inside the Wolf.” Through the eyes of a woman who has shunned her roots, Rowland excavates the generational impact of two shootings — 30 years apart — in a small North Carolina town, while taking a deep look into the culture that allows this tragedy to proliferate.

Rachel Ruskin returns to her hometown of Shiloh after 20 years of avoiding her past to reside in a houseful of ghosts. Her family is dead, her brother Garland from suicide nine months ago, then her parents in a recent accident. Her career as an academic in New York City is also dead after she’s denied tenure and fired. Now the sole heir to her family’s farm, Rachel is rudderless, haunted and unsure what’s next.

She’s reminded that Shiloh is a place where “insisting on privacy is a snub” when she stops by The Bar — the only business in town besides the post office. Hit with a déjà vu of names and family resemblances, if not familiar faces, she learns she isn’t the only resident working through PTSD — Post Traumatic Southern Disorder — as she starts to observe how Shiloh has changed and how it’s stayed the same.

One thing that hasn’t altered: the pervasive gun culture. Before she enters The Bar the first time, Rachel meets Tom Langley, a 10-year-old sitting on the front steps with an unloaded shotgun and a mopey face. He’s a softhearted kid who was given the gun to toughen him up. Through Tom, one of Rachel’s ghosts seems to manifest in physical form — her childhood friend Rufus “Professor” Swain.

Rowland’s use of allegory and symbolism slowly builds parallel worlds as Rachel’s self-contained examination of the Old South set against the new takes shape. Her narrative alternates from 1985 to 2015, and all points in between, as history is quick to repeat itself when Tom and his sister are involved in a shooting — just as Rachel, Garland and Professor were in 1985.

Rachel sinks into a moody, isolated existence as Rowland focuses the story on her inward journey to understand how the people of Shiloh can still prioritize their 2nd Amendment rights over the lives of their children. Rachel has spent the last 20 years intellectualizing her Southern identity into an academic study of how folklore has shaped white supremacy. But her dissertation failed. Perhaps her understanding of Southern identity isn’t as comprehensive as she believes?

“We create myths so we can forget the past,” Rachel proclaims after Tom’s shooting forces her to admit that aspects of the Old South still reign. How else can she explain the way the townspeople grieve for the lost child but do nothing to ensure it doesn’t happen again? It’s the same way they behaved after Professor’s death 30 years before.

Rachel’s solo voyage deepens as she mourns the loss of her family, spending significant time alone in her farmhouse facing demons. With only her father’s dog as company and an occasional neighbor stopping by, she attempts to rid herself of a past that has a stronger hold on her than she realized. But Rachel can’t make peace with the ghost making noise in the attic until she empties the attic of her family’s memorabilia and sets fire to it.

Two ghosts from old Southern lore, the myth of the Witch Bride and the legend of 16th century historical figure Virginia Dare, haunt her as well. Rachel used their mythologies in her failed dissertation to illustrate a link between folklore and racism. Both women disappear in their respective tales as a means of survival. Rachel, now alone in the farmhouse trying to make sense of her ruined career, would do well to recognize a different way their legends influenced her life. But she’s slow to see the parallels between them and the choices she’s made.

Rachel’s niece serves as the first human anchor pulling her out of her abyss of hauntings and loneliness. Initially, it’s painful to reconnect with Garland’s girlfriend Jewel, mother of their infant Lyric, who is the only family Rachel has left. But it’s Jewel who forces Rachel to face her own hypocrisy in judging Shiloh for remaining stagnant while forgetting her own part in the town’s ugly history. There’s something worse than the stories people tell themselves to live with uncomfortable truths; there are outright lies.

Compelled to reveal a damaging secret she’s been sitting on since childhood, Rachel unburdens herself of a lie that Jewel believes led to Garland’s suicide. But it turns out that nobody in town wants to hear it. No matter how hard Rachel tries, she can’t drag the Old South into the new.

Amy Rowland uses a sorrowful woman’s journey to demonstrate how generations of “telling ourselves ghost stories about history we can’t face” has helped perpetuate a culture of gun violence. It’s a thought-provoking argument that delivers “Inside the Wolf’s” larger message — there are no easy answers at the complex intersection of identity and the stories people tell themselves to survive.

FICTION

“Inside the Wolf”

by Amy Rowland

Algonquin Books

240 pages, $27