Bookshelf: ‘Comfort of Crows’ inspires us to connect with backyard nature

Whether you live in a balcony apartment, a suburban neighborhood or on an estate with acreage, Nashville author Margaret Renkl wants you to know that you can witness the wonders of nature unfold in whatever constitutes your “backyard,” if you can just sit still long enough and pay attention.

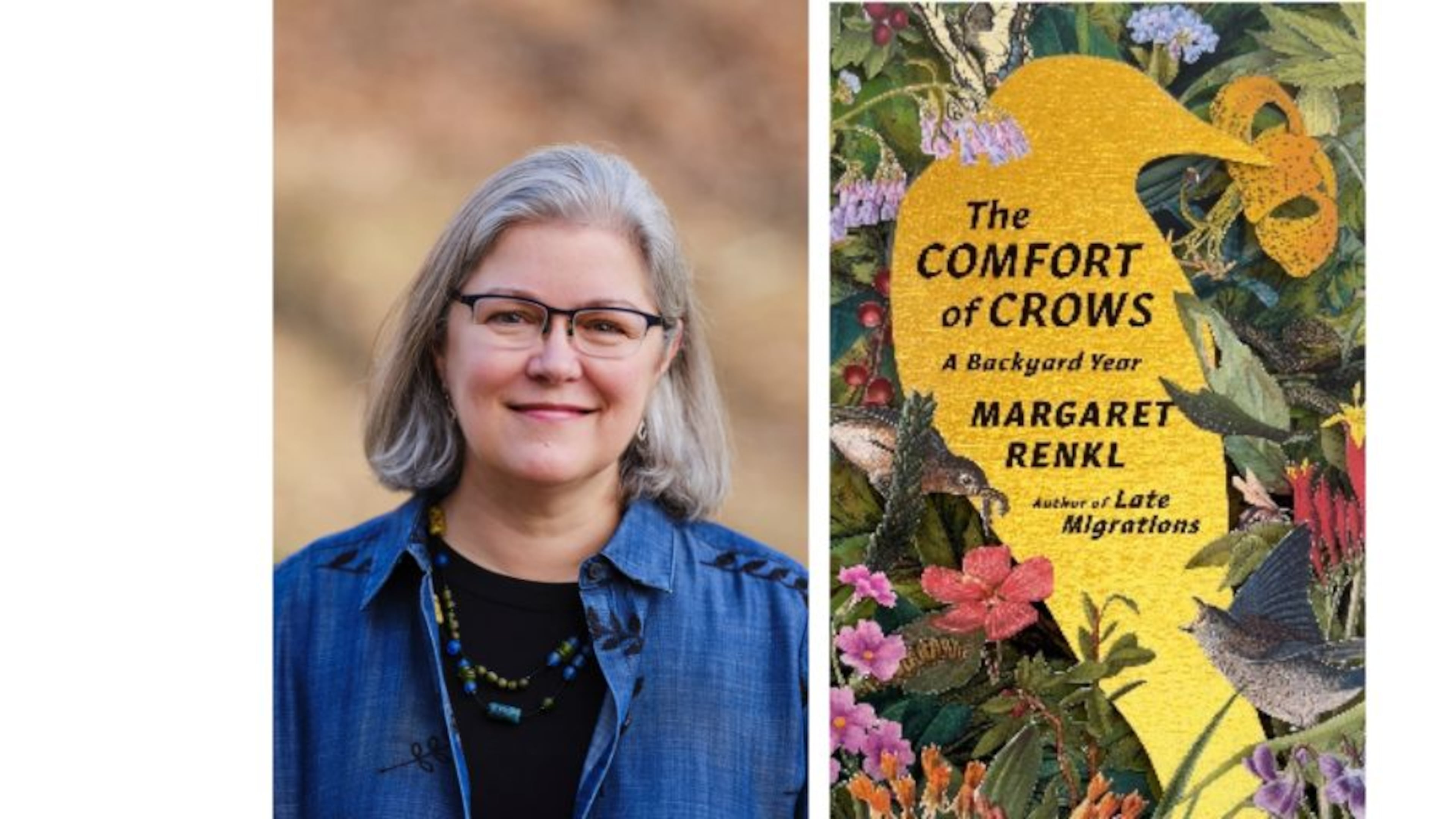

For the purpose of her new book, “The Comfort of Crows: A Backyard Year” (Spiegal and Grau, $32), Renkl’s backyard is her half-acre home in Tennessee and surrounding parklands. That’s where she draws her observations for this collection of essays that trace the cycle of nature over the course of a year.

The 52 essays were mostly written over a four-year period, with some adapted from previously published pieces, but they’re packaged in the style of a weekly devotional (without the religion) beginning with the first week of winter and ending on the last week of fall. What transpires between those two weeks contains enough beauty, heartache and hope to fill a Russian novel. Accompanying the essays are outstanding color illustrations by the author’s brother, Billy Renkl.

I am a big fan of good nature writing, and Renkl is among the best at it. I’m still marveling at the way she rhapsodizes over a toad, describing it as being “as soft as a great-grandmother you can hold in your hand.”

Author of the critically acclaimed “Late Migrations: A Natural History of Love and Loss” and an opinion columnist writing about the South for The New York Times, Renkl is clear about her agenda. She wants us to recognize that “nature is all around us and we are a part of it,” and she wants us to connect with it by learning how to quietly observe it.

“Our usual method of going through the world as a species is busyness, and we aren’t comfortable sitting still and just listening. But our ancestors, even very close generation ancestors, were,” she said when I spoke with her by phone earlier this week. “Before radio, before television, before air conditioning, we would sit on our porches or our front stoops and cool off with the breeze and listen to each other telling stories — but also listen to our wild neighbors and their songs and their quarrels and their hope.

“Our world is very different from the way human beings have lived for most of the time that we have been on this planet,” she said. “And yet I do believe … that if you slow down and sit still and listen and look, (nature) will come to you, it will unfold before you. You won’t be frightening everything away.”

The benefits of connecting with nature are many. Big picture-wise, people are more likely to protect and preserve something that they love and appreciate. On a more individual level, it’s good for our wellbeing.

“There’s all kind of evidence that people do better in a lot of ways when they are in close proximity to the natural world in some way,” said Renkl. “There’s one study that shows that people recovering from exactly the same surgery in a hospital room recover more quickly if there’s a tree outside their window. There are multiple studies that show when you have your hands in the dirt and you’re turning soil, you’re releasing microbes into the air that stimulate serotonin production in the same way that an antidepressant does.

“The cumulative effect of what we know about ourselves is that we are also creatures and we belong to this very world that we have walled ourselves off from,” she said. “And if we can find our way back to it, we will be happier, calmer, more at ease. And I think healthier.”

One of the ways Renkl fosters that connection is by leaving parts of her yard in its natural state. She doesn’t deadhead her flowers and lets them go to seed. She doesn’t mow the parts of her lawn she doesn’t use. She stacks fallen limbs instead of running them through the chipper. This way, she creates a source of food and habitat for various critters.

“What I have found in my own life is that small steps lead to bigger steps because they are self-reinforcing,” she said. “So you plant a pot of milkweed and you see a monarch butterfly land there. It makes you so happy that you just want to dig out a whole flower bed next year … Baby steps are still steps.”

If you do sit quietly and watch nature long enough, the likelihood is good you’ll eventually witness the food cycle in action. Renkl addresses this unpleasant fact in the book with a couple of anecdotes about trying to protect bluebirds from a Cooper’s hawk and a house cat.

She discourages intervention in the natural process. After all, the Cooper’s hawk is as integral to the ecosystem as the bluebird. That he eats bluebirds to stay alive is just a fact of nature. But house cats don’t naturally occur in our ecosystem, so she advocates for keeping them away from vulnerable creatures.

Nevertheless, creatures eating other creatures is the natural order of things.

“It is hard to witness,” she said. “It takes some practice, but the more you see it and the more you recognize how it works in an integrated system that is much bigger than we can even begin to understand, the more you see that the way it works itself is a beautiful thing. When we don’t interrupt it with our machines and our poison and our changing climate, it works itself out in the way that it should. That way of seeing the world is very comforting when you get there.”

As much as “The Comfort of Crows” is about nature as it cycles through the seasons, it’s also about the passage of time and the seasons of our lives. One informs the other as Renkl weaves in observations about the death of her parents and her adult children moving away, not to mention her own mortality.

“To see all of that happen on a faster scale with the birds in my yard or the chipmunks or the possums helps me remember that this is also just the way life works,” she said. “And while I don’t miss my parents any less because of it or miss my children around the table every night after school, I do take some comfort from the idea that I am part of this bigger thing and it’s natural. It’s the way the world is supposed to work.”

Margaret Renkl will be in conversation with Teresa Weaver at the Atlanta Botanical Garden on Oct. 17. Tickets are free, no registration required. It also will be livestreamed on the garden’s Facebook page. For details go to atlantabg.org.

Suzanne Van Atten is a book critic and contributing editor to The Atlanta Journal-Constitution. You can contact her at Suzanne.vanatten@ajc.com.