That victory dance, on the roof of the world, took chutzpah.

After grueling weeks in the cold, thin air of the Himalayas, mountain climbers tend to get punchy. For Atlantan Mimi Zieman, the only woman in a 1988 expedition attempting to summit Mt. Everest, the time seemed right to goof off. So, she donned her tie-dyed tights and tap shoes and did a jaunty little jig. Then she taught the other climbers how to do “jazz hands” in their gloves. The giddy moment, captured in a priceless snapshot, was hard-earned, as she explains in her gripping memoir, “Tap Dancing on Everest: A Young Doctor’s Unlikely Adventure” (FalconGuides, $22.95).

“I called it my Guinness World Record-breaking highest altitude tap dance,” she writes.

Zieman has produced a book that manages to be several things at once: It’s a ripping yarn, a coming-of-age story, a vivid travelogue, a medical memoir, a heartfelt paean to the great outdoors and a feminist exploration of identity — heady themes worthy of the high-altitude backdrop. Zieman’s writing is as sure-footed as her crampons, and mountains make for handy metaphors.

“I wanted to explore the risks we take to become our truest selves,” she says.

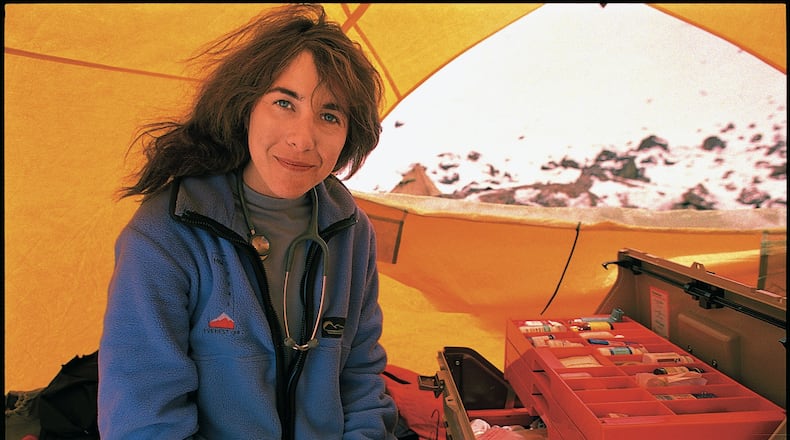

Zieman was a 25-year-old medical student when she signed on to serve as doctor for a small, scrappy team attempting a new route on the remote East Face of Everest in Tibet. Only one other team had successfully negotiated that pass. Her goal would not be to reach the summit but to accompany the team on its arduous, four-month trek and provide health care.

Gung-ho purists, the all-male crew broke from custom and embarked without sherpa support, supplemental oxygen or a rescue plan in place. When three of the climbers — one Zieman’s lover — disappeared in the vast whiteness, she had to tap into inner resources she did not know she had.

Credit: FalconGuides

Credit: FalconGuides

“The mountain that had enticed me, made me feel more alive than ever, challenged me in ways I’d never expected and then imperiled my team,” she writes, “I was furious at that mountain even though I had wanted more than anything to live in its shadow.”

More than 340 people have died attempting to reach or return from the summit of Mt. Everest, which looms 29,031 feet above sea level. Every slippery crevasse promises disaster, and every loose rock an avalanche. As if that were not enough, Zieman was almost trampled in a yak stampede.

Medical maladies abound in these extreme conditions — altitude sickness, edema, hypoxia, frostbite, snow blindness, retinal hemorrhage and infections that can quickly turn into deadly gangrene or sepsis are just a few. Any doctor would stay busy — while trying to survive herself — and Zieman proved an indispensable healer.

A magazine article about the team’s preparation described her as an “unlikely” mountaineer, and she does not argue the point. “I was a nice Jewish girl from the city, not the outdoorsy type — at first.” Zieman grew up in the gritty New York City of the 1970s, the daughter of flinty, resilient Holocaust survivors in an Orthodox home. “My parents and grandmother were very bold, strong people who had relied on their wits to survive, so their example, and possibly their genetics, influenced me,” she says. (Her faith proves sustaining — at one point, she holds a makeshift seder on Everest.)

An introverted bookworm who struggled with her weight, she was born with misshapen legs and wore them in a cast for one year — not an auspicious beginning for a world-class hiker. But she took up dance and worked at achieving double-jointed grace, gradually becoming more at ease — exultant even — in her body.

Her first gynecologist was brusque and intimidating, and Zieman made the decision then that she would become a different kind of doctor, one who puts her patients at ease. Toward that end, she pursued her degree in biology at McGill University in Montreal. There, at age 19, she saw a flier that would change her life. It advertised work at the Rocky Mountain Biological Laboratory in Colorado.

“The day I arrived, I was eager to join other new students on a hike to a waterfall,” she writes. “Someone spread out a topographical map, and I got my first look at dashed-line trails with peaks, saddles and blue rivers squiggly as varicose veins.”

So different from New York’s subway grid. Zieman was hooked. “I fell in love with the mountains right then and there,” she says. “The feeling of wilderness, clean air, wide-open spaces, changing clouds — I was instantly happy.”

She writes, “A craving took root. To return again and again to the mountains.”

Zieman continued her education, enrolling in Albert Einstein College of Medicine in the Bronx. “It was a strange juxtaposition,” she recalls. “I was treating gunshot wounds on a Saturday night while studying and dreaming of mountaineering.”

She went solo backpacking in Nepal and fell into alpinist circles. Another climber — an on-again, off-again boyfriend — came up with the ambitious plan she could not resist: to scale Everest.

Credit: Mimi Zieman

Credit: Mimi Zieman

Known in climbing circles as the Everest ‘88 Kangshung Face Expedition, the venture made history. Team member Stephen Venables became the first Briton to summit without the use of bottled oxygen. Americans Ed Webster and Robert Anderson made it to the South Summit but did not reach the main peak. Everyone did make it home, eventually.

Afterward Zieman returned to her studies. Following a fellowship in San Francisco, she moved to Atlanta in 1995 to serve as director of family planning at Emory University Medical School. “I took the risk-taking I learned on Everest to create a varied career in OB/GYN, moving between work in academia, nonprofits, industry, the arts and as an entrepreneur.”

Now semiretired, she has been writing, contributing pieces to Newsweek, Salon, The Sun, Ms. Magazine, The Forward and THINK.

She drew from her detailed journals to write “Tap Dancing on Everest.”

“Mimi Zieman’s book appears at an exciting time in mountain literature when women and other underrepresented writers are increasingly transforming the genre, overturning old formulas and stereotypes and featuring tales of experiences that have long been left out of dominant narratives,” says Katie Ives, former editor-in-chief of Alpinist and author of “Imaginary Peaks: The Riesenstein Hoax and Other Mountain Dreams.”

The book is “fiercely feminist,” says Zieman’s agent, Erin Clyburn. “It’s a story about being the child of immigrants, it’s a story about becoming a physician, and how all of these identities come together to empower Mimi to accomplish really incredible things.”

Zieman is also the author of a medical text, “Managing Contraception,” and a play, “The Post-Roe Monologues,” which was staged by The Temple on Peachtree Street.

“I’m an outspoken advocate for reproductive rights,” she says.

She credits mountaineering for helping find her voice.

“It would be a long time before I’d understand everything we’d been through on that glacier,” she writes, “that I’d experienced the greatest emptiness and the greatest strength there. Now I realize that living and loving, while knowing all could be lost, is the essence of the greatest aliveness.”

About the Author

Keep Reading

The Latest

Featured