John Lewis grew up in an Alabama family so poor that he and his young cousins once had to shuttle from room to room, acting as “ballast” to keep their aunt’s house from blowing away in a windstorm.

Born in 1940, he came from deep within the country, but he hated farm work and made no secret of it. As a boy, denied a library card because of his race, he still managed to study Booker T. Washington’s “Up from Slavery,” though he liked reading the Bible most of all.

If, in a famous anecdote, he truly delivered barnyard sermons to chickens, they were likely a more attentive audience than much of the U.S. Congress, where he would reside for 17 years as the representative for Georgia’s 5th District until his death in 2020. It hardly needs to be said that, even in his lifetime, John Lewis became the most revered and broadly loved politician in Georgia’s history.

Traumatized by the gruesome Mississippi murder of Emmett Till in 1955, Lewis experienced a moment of illumination one year later when he tuned into Rev. Martin Luther King Jr. on a Montgomery AM radio station: “I heard this voice on the radio and that changed my life.”

By the time he was 21, he no longer aspired to be a minister in the traditional sense, having embraced the “social gospel.” Here, now fully committed, his biography unfolds as a danger-filled, coming-of-age adventure chronicled in sweeping detail by David Greenberg in his exceptional, tremendous biography, “John Lewis: A Life,” the source for the background mentioned above.

At Nashville’s American Baptist Theological Seminary, under the guidance of the divinity student James Lawson, Lewis studied the discipline and principles of Ghandian nonviolence suffused further with the Holy Spirit: “You have to love that person who’s hitting you,” implored Lawson. The world’s historic events to come would offer young Lewis ample opportunity to test his mentor’s affirmation.

With a combination of “steely determination” and “an unmistakable gentleness,” as Greenberg puts it, Lewis emerged as a main player in the cutting-edge Nashville Student Movement. Through “direct action” — sit-ins at diners and “stand-ins” in movie queues usually followed by arrests — they successfully integrated the town’s restaurants and theaters, an unprecedented leap for a major Southern city in 1960.

The following year, during the violent response to the Freedom Rides — an interracial campaign testing the U.S. Supreme Court rulings desegregating public transportation — Lewis was so badly pummeled by racist toughs in Rock Hill, South Carolina, and Montgomery, Alabama, that scars would remain visible on his head for the rest of his life, according to the eminent Civil Rights historian, Raymond Arsenault.

He had neither the exquisite speaking voice of his hero, King, nor of his close friend, Julian Bond, who tutored him on his media presentation. Lewis “spoke haltingly and with a mild speech impediment,” yet he had an eloquence of being, making the most of his dilapidated shoes and thrift-store suit. As chairman of the Student Nonviolent Coordinating Committee (SNCC), he fearlessly addressed 250,000 at the 1963 March of Washington and tens of millions of television viewers.

Credit: Jackson Police Department

Credit: Jackson Police Department

Then came the iconic scene of rural resistance to voter suppression: March 7, 1965, “Bloody Sunday,” at the top of Selma’s Edmund Pettus Bridge, when he and his fellow marchers confronted Alabama State Troopers and police wielding bullwhips and batons. The author captures the hush of anticipation: “a breeze brushed Lewis’ trenchcoat and skimmed the water below.” Moments later, lying on the ground with a fractured skull, John Lewis “realized that he did not fear death. A feeling of peace and serenity — even lucidity — came over him.”

Having pushed the Johnson administration to secure the Civil Rights Act of 1964 and, after Selma, the Voting Rights Act of 1965, the movement, with its allure of “churchiness,” began to fade, splintering into more militant factions with the new wave of Black Power at odds with King’s interracial dream of the “Beloved Community.”

Ousted from his SNCC chairmanship in a sleazy midnight ploy — well documented by Greenberg — Lewis was cast adrift. For a short time, he rediscovered a “cocoon of belonging,” joining the 1968 Presidential campaign of Robert Kennedy.

He was with RFK in Indianapolis when King was murdered in Memphis; he helped arrange for Kennedy to have the fallen leader’s casket flown to Atlanta. Two months later, he was on an upper floor of the Ambassador Hotel in Los Angeles when RFK himself was gunned down in the kitchen below.

Given these devastating emotional blows, Lewis was briefly hospitalized in Atlanta to recuperate. He had little personal life: “If Atlanta was a city too busy to hate,” quips Greenberg, “Lewis was too busy to date.” But then he met Lillian Miles, a university graduate from California, whom he married. “Cultivated, elegant and ambitious,” she renewed his confidence, and, in 1976, he cocked his hat for public office, running for Congress. Though he fell short, he was elected to the Atlanta City Council in 1982.

“John Lewis: A Life” is a thoroughgoing primer for Atlanta’s increasingly tangled political world during the ‘70s and ‘80s. Lewis promoted a stricter code of ethics, for which his colleagues shared little enthusiasm. He became a pioneering and enduring supporter of the city’s gay communities. (As his friend, Joseph Larche, later said, “He wanted people to have the opportunity to love who they wanted to love…”)

A foe of antisemitism, he was a cofounder of the city’s Black/Jewish Coalition. (Crucially, Greenberg elaborates, “Lewis recognized the difference between criticism of Israel and antisemitism.”) And, as an early exponent of “environmental justice,” he opposed the Presidential Parkway, a project that turned into a bitter, decade-long row presaging, in several ways, today’s brutal “Cop City” clash.

Greenberg devotes a full chapter to the divisive congressional race between Lewis and Julian Bond in 1986. They’re known as the “Civil Rights Twins,” but, as the contest tightened, Lewis insinuated that Bond was a drug user. While he won the seat in an upset, it was an unbecoming, and uncharacteristic, episode in Lewis’ political career, for which he would, at a later date, confide his regret.

Credit: Simon & Schuster

Credit: Simon & Schuster

Nevertheless, the close-fighting skills he learned in urban politics served him well in Congress. During the Clinton years, he battled Newt Gingrich ferociously. Later, in Greenberg’s description, he became “the anti-Trump, a symbol of charity over spite, gentleness over anger, compassion over discord, hope over fear.”

“His sharpest weapon” was “his moral authority,” which he deployed when he shamed George W. Bush into signing the Civil Rights Act of 1991. (Currently, the John R. Lewis Voting Rights Advancement Act is in legislative limbo.)

Indeed, Lewis developed a flair for creating temporary, bipartisan coalitions to advance his agendas. At a succession of annual commemorative gatherings in Selma, he helped bring together many old comrades and adversaries. He played the decisive role in establishing the National Museum of African-American History and Culture, his triumphant cultural achievement, a consequence of delicate negotiations lasting two decades.

The walls of his home were festooned with brightly colored African-American folk art. “He never acquired airs,” but he had small “vanities,” e.g., tailored suits and expensive antiques.

He could be a bit of a square — he wasn’t keen on rap — but, with aide Andrew Aydin and illustrator Nate Powell, he produced a wonderfully hip, three-volume graphic novel about his life, compiled as the “March” series, the third installment of which won the 2016 National Book Award for Young People’s Literature.

Evenhanded in his presentation of criticisms, Greenberg does not intend “John Lewis: A Life” to be a hagiography, but how does one contain a “saint,” as he’s playfully known to his family and friends? This was a man for whom a truck driver blocked traffic to shake his hand; “Visitors wept after ordinary encounters”; the airport became an “obstacle course” when he was rushing to make a flight.

Moreover, Greenberg emphasizes, “It became a familiar ritual, with Lewis as the nation’s father confessor, a wise and loving elder to whom racists turned to for absolution.” The 72-year-old Klansman who had beaten Lewis in Rock Hill begged forgiveness on “Oprah,” and, of course, Lewis, who is sitting next to him, extends his embrace.

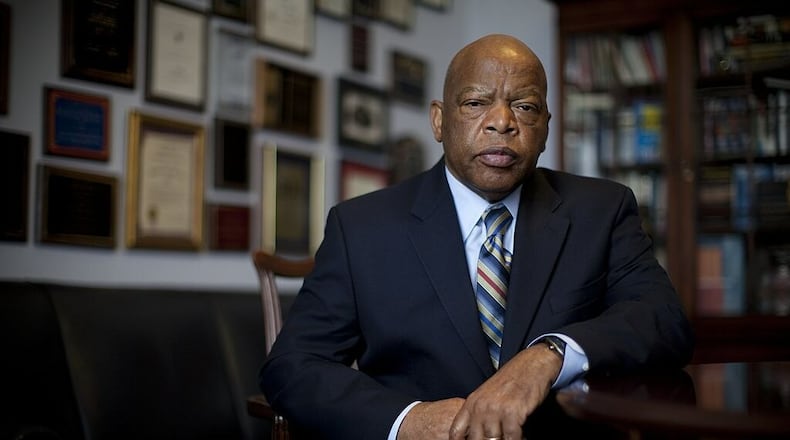

Credit: Jason Getz/AJC

Credit: Jason Getz/AJC

Boisterously funny and stern, he was gregarious — certainly a political asset — yet he “remained prone to feelings of solitude.” When displaying either vulnerability or anger to the outside world, he wasn’t shy.

Thus, David Greenberg captures the cool of Lewis’ Buddha-like bearing and the heat of his steady flame. But Lewis’ complex personality, like Lincoln’s, defies easy understanding, and, at times, he had the rare, elusive appeal of an American life force that was somewhat mysterious, a phenomenon Lewis himself didn’t understand, but came to accept.

When he died in 2020 of pancreatic cancer, Greenberg observes, “The celebration of Lewis’ life surpassed anything yet seen for a U.S. congressman … the farewell spanned six days and five cities.”

In August 2024, his statue replaced a moldy Lost Cause obelisk on Decatur Square. This likeness, cast into bronze by sculptor Basil Watson and named “Empathy,” faces up with eyes closed, as if its subject had a deep feeling for passing clouds full of rain and change, which John Lewis did. Of his passion for gardening, he once said, “I fertilize the flowers and hope and pray they will be beautiful.”

AUTHOR APPEARANCE

“John Lewis: A Life.” Author David Greenberg delivers the Livingston Lecture on John Lewis. 7 p.m. Oct. 9. $12. Atlanta History Center, 130 W. Paces Ferry Road, Atlanta. 404-814-4000, www.atlantahistorycenter.com

NONFICTION

“John Lewis: A Life”

by David Greenberg

Simon & Schuster

704 pages, $35

About the Author

Keep Reading

The Latest

Featured