How University of Georgia helped put a man on the moon

How did a professor of animal husbandry, who studied broiler chickens, get involved in the space race?

Better yet, how did an Athens supercomputer help the University of Georgia win football games?

Both things happened because a man named James L. Carmon, a professor in the School of Agriculture, talked his school into buying the biggest, costliest computer in existence.

In 1964, that computer was the IBM 7094, a mainframe that took up an entire room and cost $3 million (about $25 million in 2019 dollars).

Carmon was betting, in 1964, that computers would not only be useful but critical. He gambled that the expensive machine would eventually pay for itself. He bet right. Soon a customer came along who needed just that kind of computing power: NASA.

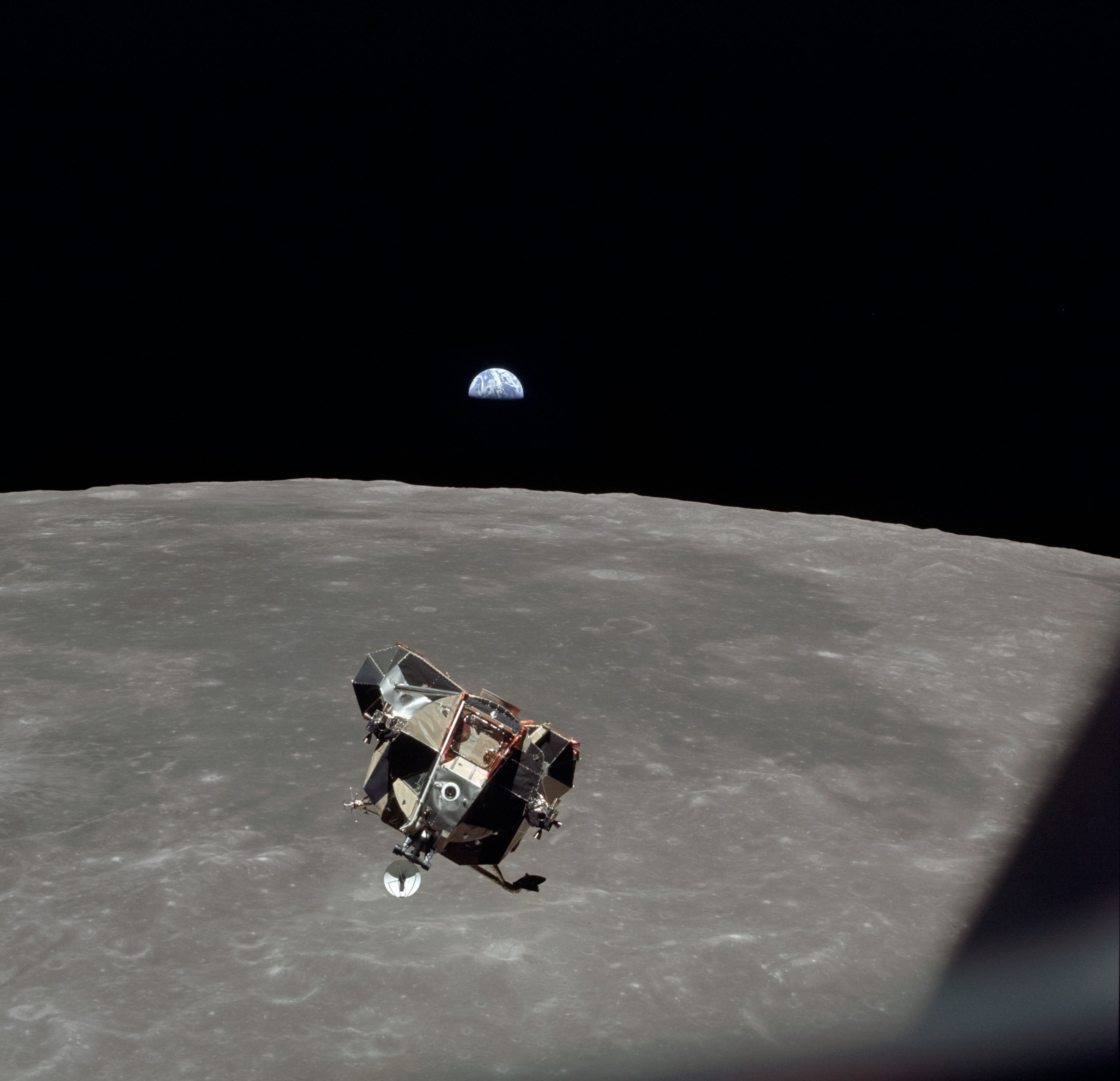

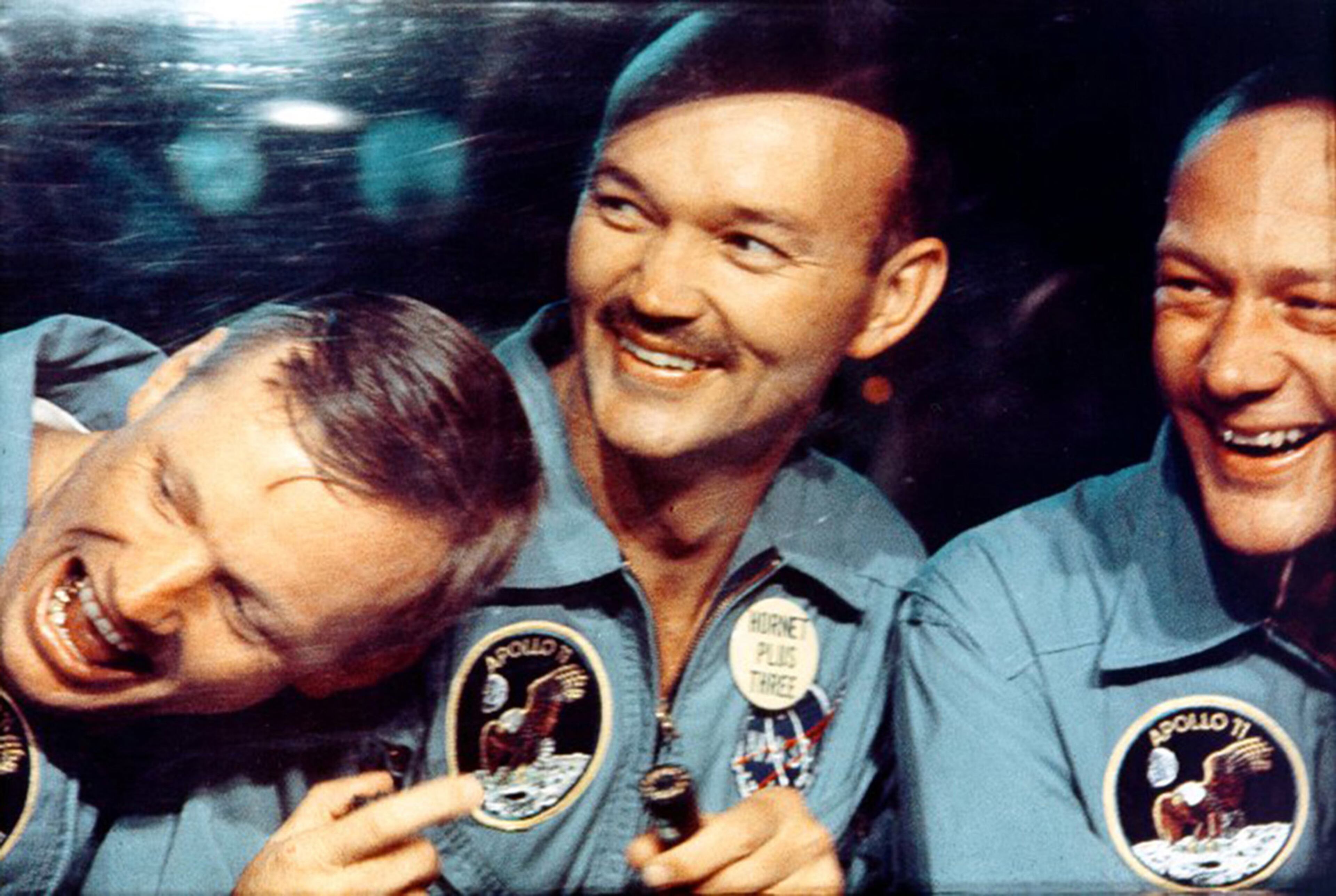

Fifty years ago, humans slipped the surly bonds of Earth and walked on the moon. That achievement will be celebrated this week around the world and in Georgia. At the University of Georgia, there will be an array of space-race artifacts on display at the Richard B. Russell Special Collections Libraries, including an exhibit of moon rocks.

> More Atlanta area events where you can celebrate the moon landing's 50th anniversary

Not on display will be the computer that helped make it happen, and helped train a generation of computer scientists at UGA.

A vision that paid off

The story of UGA’s contribution to the space program (and computer-assisted football) began with a man from a North Georgia farming family who specialized in both animal husbandry and statistics.

Carmon was a professor in experimental statistics in the School of Agriculture. His research projects included “Type-of-Rearing and Location Effects on Broiler Body Weights” — i.e., the factors that make a chicken fat.

But his true love was computers. The bigger the better.

His daughter, Lee Carmon, said her father began in agriculture because that’s where he won his scholarships as an undergraduate, and when he joined the University of Georgia faculty in 1950, he chose the School of Agriculture because that’s where the job opening was. But his interest was in statistical analysis and the big computers that made statistics work.

“He had such a vision,” said the daughter, now a resident of Athens, Georgia, “and I think he was very persuasive in getting others to be excited about that vision.”

“He was always intrigued by acquiring the largest and fastest,” said Walter McRae, who was hired by the university in the early 1970s as a programmer and eventually directed the computing center.

The IBM 7094 was installed in the Lumpkin House, a former residence that became UGA’s silicon valley. The multi-ton machine was so big that parts of it had to be suspended from the ceiling.

“I’m willing to guess that, at that time, the University of Georgia was the only research university in the Southeast that had such a machine,” said McRae.

The 7094 was used for statistical research projects, but was also soon in demand among such customers as the Southeastern Power Administration (which was responsible for marketing electrical power from Army Corps of Engineers dams) and the Georgia Department of Transportation, which rented time on the machine in its off-hours.

Carmon told McRae that he was so successful at leasing time on the 7094 that he paid off the $3 million cost in a year.

Keep in mind that the IBM machine had a memory of between 32 and 150 kilobytes, or one-millionth the capacity of your iPhone, and was programmed with the use of punch cards. Hundreds of punch cards might be necessary for a single program.

Yet the machine represented the state of the art in computers. NASA had its own 7094 at the Redstone Arsenal in Huntsville, Alabama. The space agency, McRae said, was committed to using the 7094 architecture throughout the Gemini and Apollo programs, despite the fact that newer machines were already in development.

So when NASA needed extra time on a machine and theirs was busy, they could drive over to Athens, bring their own crew, programs and tape drives, load up the UGA machine and go to work. “There was a natural synergy there.”

Related: How the AJC covered the moon landing.

McRae said among the NASA contractors using UGA’s computer were the designers at Lockheed, who were responsible for creating the propulsion systems for the Gemini and Apollo rockets. McRae said scientists with NASA also used the UGA machine to analyze orbital data from Gemini missions, in which astronauts practiced docking maneuvers in low orbits.

A popular numbers cruncher

There was also another customer for the school's new computing capacity. Football coach Vince Dooley, hired in 1964, began using the 7094 to assemble information on other SEC teams.

Dooley and his assistant coach -- probably Frank Inman -- would compile statistics on how that week’s opponent called plays from every field position and from each down and yardage, “whether it was third-and-goal or fourth-and-10,” said Dooley.

“The fellow who helped us, he knew what to put in it,” said Dooley this week, just back from a summer visit to Lake Burton. “We brought the information to him and he fed it in and got it back to us, within what seemed like 10 minutes at the most. It was an amazement to me.”

That information helped Dooley turn around a losing program and build a team with a 31-10-2 record over the next four seasons.

Did the 7094 make a big difference? “It was certainly a factor,” said Dooley.

So IBM could win football games. How important was the computer’s contribution to the space race?

In 1961, President John F. Kennedy challenged the nation with an impossible mission and a ridiculous deadline. Get to the moon before the decade is out.

A real challenge was computing capacity. There were just too many numbers to crunch. Albert DeSimone, who was UGA's first webmaster, and later served in public relations for the computer center, said that UGA had one of the few 7094s close at hand. DeSimone has documented the use of the machine, even creating a 29-minute documentary film on computing at UGA that has a lengthy chapter on the 7094.

Doug Mathews, who came to the university in 1968 as a programmer, and eventually also directed the computer center for a while, said what UGA gave NASA was time.

“I can’t say how much time we saved (NASA), but the time we leased to them was a significant step forward in absolute terms,” he said. “If we leased it to them for 24 hours, they were 24 hours ahead.”

For all its stellar accomplishments, the 7094 arrived at what McRae calls “an inglorious end.”

“Those things are big machines. They take up a lot of room. They generate a lot of heat, need a lot of cooling,” said Mathews. Moore’s Law tells us that computers will drop in price by a half and double in power every two years, and the 7094’s future was limited. It was soon replaced, and by the early 1970s, it was decommissioned, surplused and sold for pennies on the dollar. It was then strip-mined for its precious metals and tossed on the garbage heap.

Legacy of 7094 lives on

Harold Pritchett, who worked in the computer center, still has a cast-off piece of the computer’s central memory core in his Athens basement. The hand-made interior features thousands of pin-head sized ferrules, strung on wires. “It’s history,” said Pritchett. But it’s forgotten history, except in a few corners of our cultural memory.

One of NASA’s missions was to help business and industry utilize the new technology created for the Gemini and Apollo missions, and one offshoot of that research effort was a flowering of software written for the 7094. Much of it was useful in design and manufacturing, and the University of Georgia was responsible for maintaining a library of that software and assisting in its distribution, in a UGA facility called COSMIC, or Computer Software Management and Information Center.

The software has since moved back to NASA, but is still in use, including a program called Nastran (for “NASA Structural Analysis”), which is used to design automobile bodies, engines, hydraulic systems and the like. McRae said most of the programs were written in Fortran, which made them compatible with more contemporary machines.

James L. Carmon, who died in 1986, is honored with a UGA scholarship in his name, funded by the Control Data Corp.

And the 7094 will live on in popular culture as the inspiration for one of the great scenes in 1968’s “2001: A Space Odyssey.”

In reality, a 7094 at Bell Labs became the first computer to synthesize a human voice. Science fiction icon Arthur C. Clarke, who wrote the novel and screenplay of "2001," listened to the 7094 singing "Daisy Bell" (or "A Bicycle Built for Two") during a visit with his friend Max Mathews at Bell Labs.

Clarke convinced director Stanley Kubrick to have the omniscient onboard computer, HAL 9000, sing the same song, as he is disassembled by astronaut Dave Bowman.

Soon, Georgia’s 7094 would suffer a similar fate.