High-tech glove that can translate sign language alphabet

For a fraction of the cost of a new iPhone, researchers at University of California, San Diego, developed a smart glove that can translate the American Sign Language alphabet as the wearer’s fingers move.

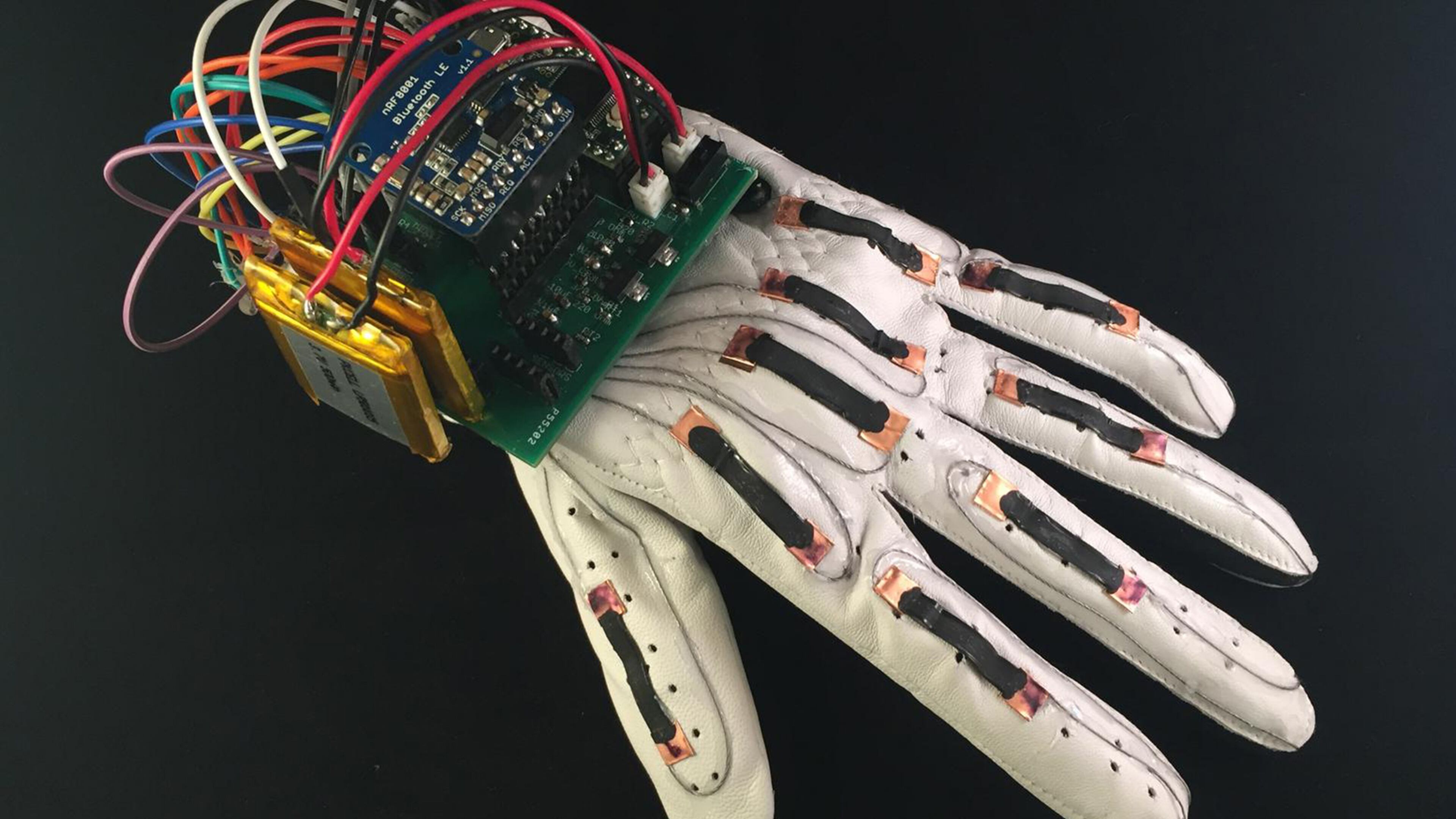

The researchers outfitted a golf glove with the electronics needed to track a signing hand and relay the letters wirelessly to a phone or computer. They published their work recently in the journal PLOS One.

The key to translating gestures is the sensors on the back of the fingers. After months of experimenting with different materials and countless hours of finger spelling, the researchers found the right material for the job, a mixture of rubber and carbon nanoparticles.

“Not only are the materials really cost effective and really cheap, but also the way you make them into devices is really cheap,” said Timothy O’Connor, the lead author of the paper and a graduate student in the Lipomi research group at UC San Diego. “You can stencil it, print it, paint it on.”

O’Connor made the sensors by painting the thin layer of conductive carbon onto a stretchy plastic. The sensors are wired into a circuit with conductive thread. As they bend with the hand’s motion, their resistance to electrical current changes. A microprocessor on the back of the hand converts the electrical signals to letters that are sent by a Bluetooth connection to an app or computer.

The researchers also had to figure out how to read letters that require your hand to move, for instance, to distinguish “i” from “j.” For “i,” one makes a fist with the thumb pressed against the palm, fingers curled over it and pinky finger up. Flicking the wrist down and to the right turns “i” into “j.”

To track motion, the researchers added an accelerometer, the gadget in an iPhone that detects if the phone is tilted one way or another. All the glove’s components cost less than $100.

Gloves that can translate the sign language alphabet have been made before, but many of them rely on flexible electronics that can bend but can’t stretch the way human skin can, said O’Connor.

He said of the sensors in his glove: “They’re so thin and so stretchy that you can’t feel like they’re there.”

Wearable stretchy electronics are bringing technology closer than ever to our bodies and can be used to unobtrusively track vitals such as heart rate and breathing patterns. Scientists have even developed sensors that can track irregular swallowing for people who have been treated for throat cancer. This glove shows how stretchable electronics can change the accessibility landscape.

“We wanted to … inspire people to imagine how much value these types of new technology could provide to people,” O’Connor said.

“It’s a big deal. … This will certainly facilitate communications,” said Yong Zhu, an associate professor of mechanical and aerospace engineering at North Carolina State University who also researches stretchable electronics. Because of its low cost, that sort of device could have a future as a commercial product, he said.

The next version of the glove will have a smaller flexible processor and sensors that can do more, such as detecting pressure. With more closely spaced sensors and a lot of programming and testing, such a glove could be used to translate a more extensive American Sign Language vocabulary beyond the alphabet, said O’Connor.