With deals in baseball, opting out is very in

Dave Dombrowski had never given an opt-out clause. He had never seen a benefit for his team and had never faced the choice that confronted him this winter, his first as president of baseball operations for the Boston Red Sox. Dombrowski could give an opt-out to the free agent David Price or miss out on the ace his team needed.

“For years we’ve negotiated dollars, length of contract, awards packages and other benefits like suites,” said Dombrowski, a top executive with several teams for decades. “But now, all of a sudden, this has become another point of negotiating. Some people are willing to give it, and if you don’t give it, you know you have a chance of losing the player.”

Across baseball, this has been the winter of the opt-out clause. The New York Mets’ three-year, $75 million deal with outfielder Yoenis Cespedes, which allows him to make $27.5 million if he opts out after 2016, is only the latest instance.

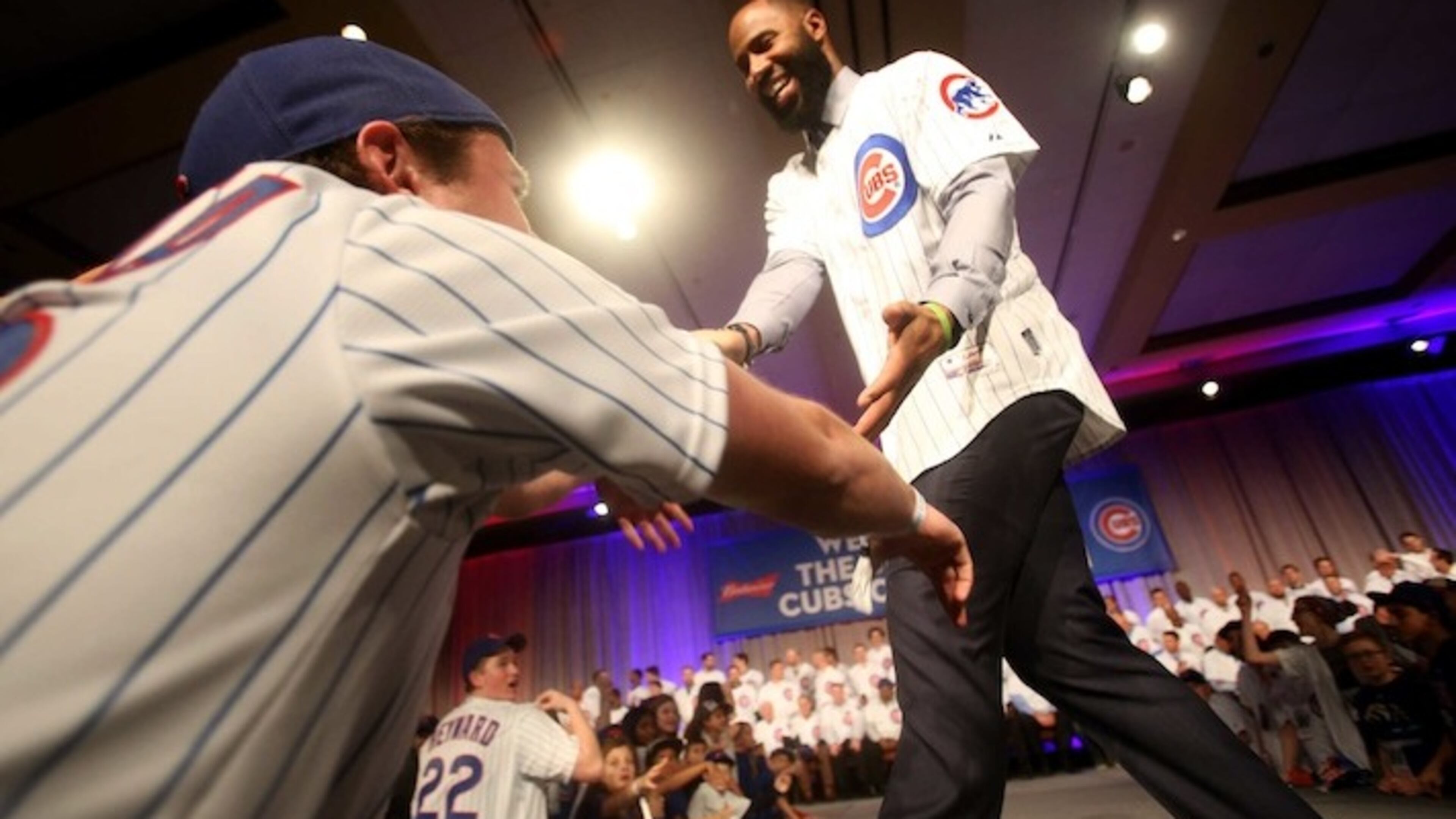

Jason Heyward, Justin Upton, Johnny Cueto, Wei-Yin Chen, Ian Kennedy, Scott Kazmir and Price have also signed long-term deals with an early escape hatch. Zack Greinke exercised the opt-out clause in his Los Angeles Dodgers deal and used it to snare a six-year, $206.5 million contract from the Arizona Diamondbacks.

Once an exception, the opt-out clause has become the norm. In a telephone interview, Commissioner Rob Manfred credited agents for skillfully using leverage but emphasized the “disproportionately pro-player” aspect of the clause.

“The only scenario where you can say, with certainty, that the player is not going to opt out is if he’s had a career-ending injury or he has performed at a level that is so far beneath the value of those out-years that nobody’s going to duplicate it,” Manfred said. “That’s the only time the player is going to stay in that contract. Otherwise, you’ve lost control of the player.”

Manfred added: “If the player’s been good, the club’s going to want to keep him. So you end up either losing him or paying him even more than you originally paid him. Neither of those are good outcomes.”

Yet there may not be much Manfred can do about the spread of the opt-out, which is also tucked into the current contracts of Giancarlo Stanton, Clayton Kershaw, Masahiro Tanaka and others. Baseball’s collective bargaining agreement expires after the coming season, and Manfred said that while it would be possible to raise the issue in negotiations with the players’ union, the sides “have not, in bargaining, tended to restrict the individual in the negotiating process.”

In some cases, teams can use the opt-out clause as a compromise that to avoid an uncomfortably long commitment. Dombrowski’s old team, the Detroit Tigers, signed Upton, an outfielder, this month to a six-year contract worth $132.75 million. But Upton, a three-time All-Star who is only 28, had hoped for a longer deal than Detroit wanted to give. The solution was an opt-out clause after 2017, which would allow Upton to become a free agent again at age 30.

“In our specific case, we felt that if we weren’t getting the length, we had to have an opt-out in the deal,” said Upton’s agent, Larry Reynolds. “Understandably, you want to keep your options open. But it’s my hope that Justin has a long career in Detroit: He likes it, they like him, and hopefully it works out where it’s a longer deal.”

Price, 30, received a longer deal than Upton — seven years and $217 million, the highest value ever for a pitcher’s contract. But Bo McKinnis, Price’s agent, said the opt-out was essential for any team that wanted him.

“I didn’t want to lock David in somewhere for seven years and have it be seven years of losing and unhappiness,” McKinnis said. “He could have received $400 million and still would be unhappy if the team was losing. He needs to win. The opt-out is the vehicle that gives David the control just in case the team doesn’t perform as planned.”

The agent Scott Boras negotiated 2017 opt-outs this month for two free-agent starters: Chen (five years, $80 million from the Miami Marlins) and Kennedy (five years, $70 million from the Kansas City Royals). In the case of Chris Davis, though, a longer-term deal (seven guaranteed years for $161 million from the Baltimore Orioles) seemed to make more sense than insisting on an opt-out clause. Davis has prodigious power, leading the majors in homers in two of the last three seasons, but an inconsistent track record.

“You have to do prognostic evaluations on players to determine which contract structure fits the player’s ability, and this is not a uniform process,” Boras said. “You really have to understand each individual player, at many levels, to know which contract methodology to use.”

Boras inserted an opt-out clause in Alex Rodriguez’s 10-year, $252 million contract with the Texas Rangers in December 2000. It was almost an afterthought at the time — buried under an unprecedented outlay of cash — but it became a major issue in 2007. Rodriguez, then a 32-year-old who was traded to the New York Yankees, had a fabulous season, opted out and got a new 10-year, $275 million deal to keep him in the Bronx.

Boras differentiates between the opt-out clause for Rodriguez — an elite player who was only 25 years old when the 2000 deal was signed — and others he has negotiated. For Chen and Kennedy, he said, the opt-out serves as a safe deposit box. The guaranteed years set up a player’s family, and the opt-out clause gives him the choice to open the box and add more.

A three-year deal between the Yankees and reliever Rafael Soriano, signed in January 2011, gave Soriano the right to opt out after the first or second year. Soriano had just earned 45 saves for Tampa Bay but did not have a long history as a closer. When an injury to Mariano Rivera thrust him back into that role in 2012, Soriano pitched well, opted out, and got a richer deal with Washington. Boras called that structure the “drive-through” contract.

“That’s where you have a three-year guarantee, but you can drive through the window and you can either pick up the Happy Meal or you have the choice of getting back on the freeway and trying to find an eight-course dinner — the long-term deal,” he said. “And surprisingly, the Soriano contract has the most value to the majority of the players in the game, and no one talked about it.”

Cespedes’ deal with the Mets does not include another opt-out after the second year of the contract, giving him one shot to secure the kind of long-term deal he initially expected to find on the market. If he opts out, the Mets can make him a qualifying offer and secure a draft choice if he then signs elsewhere.

The agent Brodie Van Wagenen, who led the Cespedes negotiations for CAA Sports and Roc Nation Sports, said he hoped the deal would be “a bridge to an even longer-term partnership” with the Mets and appreciated the club’s willingness to front-load the deal. From the Mets’ perspective, the opt-out was always in play as a tool to keep Cespedes while minimizing long-term risk.

“I thought it would be highly unrealistic that we would get a shortened term without some sort of opt-out clause,” general manager Sandy Alderson said. “And the value of the opt-out clause, from our standpoint, was a shorter term — which happened to be important to us. The only way the shorter term was going to make sense for the player was with the opt-out.”