The black decals and the black stripe on the helmet aren’t what Don Lindsey remembers about the Black Watch defense 25 years later.

“That is really insignificant,” said Lindsey, defensive coordinator of one of Georgia Tech’s all-time defenses. “It’s the people that make it what it is.”

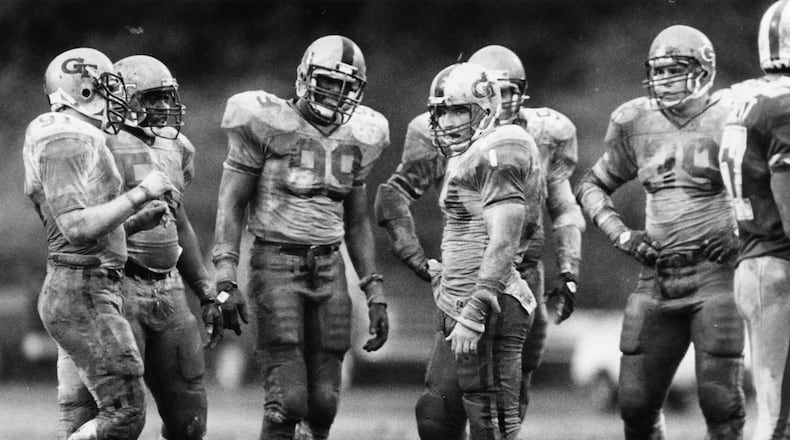

On Saturday, the Yellow Jackets faced No. 4 Notre Dame in the uniforms of the defense that laid waste to the ACC in 1984-85 and came to be known as the Black Watch. Speaking bfore the game, the coach responsible for bringing it to life showed that he holds dear memories of that defense and his time at Tech.

“I just know that they took it and ran with it,” Lindsey said. “It was really a joy to watch them play.”

When he arrived in March 1984 to replace Rick Lantz, who had left to join Notre Dame’s staff, there was question about what sort of defense he would use.

“My approach was always this,” Lindsey said. “When someone would say to me, ‘What kind of defense are we going to play?’ I’m going to say, ‘With 11, since that’s the rule.’”

In talking with the staff he joined and reviewing game video, he realized he could do something with linebackers Pat Swilling and Ted Roof and others.

Rather than having Swilling in a position where he was sometimes dropping back into pass coverage, Lindsey said, “I said, ‘My goodness, I want him rushing the passer.’ He was, if not the one, one of a number that I looked at and said, ‘I’ve got to build something to utilize that talent' and put him in a position to use what I saw as God-given talent.’”

Lindsey had had a highly successful run to that point. He began his career at Alabama in 1965 on the staff of Bear Bryant, helping the Crimson Tide win the AP national championship that year. He later joined John McKay at USC, rose to become defensive coordinator and helped the Trojans win three national championships. At the time Curry contacted him about the job at Tech, he had actually decided to leave coaching, having resigned from Lou Holtz’s staff at Arkansas in 1983.

But he took the job, won over by Curry and athletic director Homer Rice.

“Two men of great character,” he said. “It’s not every day you get a chance to work for two people like that.”

Safety Cleve Pounds remembers an initial meeting with the defense with Lindsey, when he rattled off the accomplishments of teams and defenses he had coached. Then he asked what the one constant had been with those teams.

“Everybody kind of looked around, and I think everybody said, ‘Well, you won,’” Pounds said. “And he said, ‘No. Me.’”

It was meant as an icebreaker, Pounds said, but also “a moment of, ‘Let me tell you, I have history with this. This is not my first rodeo.’”

With Swilling at the “strike” linebacker spot in the 3-4 and a defense predicated on attacking, the Jackets took off. Tech’s scoring defense dropped from 28.4 points per game in 1983 to 18.3 points. Total defense shrank from 407.9 yards per game to 317.3. The Jackets led the ACC in both categories.

Led by Swilling and Roof, the Jackets recorded 19 sacks and 35 tackles for loss in 11 games, up from 14 and 26, respectively. More notably, Tech improved from 3-8 to 6-4-1 and ended its six-year losing streak to Georgia.

Pounds remembered Lindsey as intense but fair, and also someone who took the time to get to know all of his players.

“He wanted us to play aggressive,” Pounds said. “He didn’t want us to let the offense dictate how we would play. He wanted us to dictate to them.”

Credit: Georgia Tech Athletics

Credit: Georgia Tech Athletics

In 1985, the play only improved. The defense gave up 10.7 points per game, which led the ACC, was ranked fourth in the country and is the lowest season average for Tech in the era since coach Bobby Dodd’s retirement after the 1966 season. Since Lindsey, Tech has not led the ACC in total defense or scoring defense.

Swilling was named an All-American with 15 sacks (still a school record), 21 tackles for loss and 30 quarterback pressures. Tech finished 9-2-1 and ended the season ranked 19th, its first time in the season-ending Top 25 since 1972.

“Oh, my goodness, he performed,” Lindsey said. “The statistics speak for themselves and the videotape or film speak for themselves.”

It was before the 1985 season that Lindsey hatched the idea of a club made up of the most physical players on the defense, a way for players to recognize one another. Swilling, Roof and Pounds were among the charter members, along with linebacker Jim Anderson and safety Riccardo Ingram. They were identified with a black “GT” logo on the helmet and a corresponding black stripe down the center of the helmet, the look that the Jackets wore (along with black jerseys and gold pants) Saturday.

“It was totally a team effort,” Pounds said. “We totally believed in one another, we believed in the process, we believed what coach Lindsey was preaching and everybody bought in.”

Pounds said that being a Black Watch member was a badge of honor. Membership was earned.

“The way you got someone’s attention is you went out there and put someone’s butt on the field,” he said. “That’s it. That was the rule of the game. Your actions speak for you.”

Lindsey stayed one more season at Tech and then went with Curry to Alabama. He coached at several more stops, including Missouri, Hawaii, USC (a second time), Ole Miss and the CFL.

He appreciated the school’s academic rigor. He remembered having a walk-on linebacker who was an aeronautical engineering major. He appreciated working for Rice and Curry.

“He didn’t have to have anything to do with me,” Lindsey said of Rice. “I’m just an old assistant coach and he’s got all the sports and all the things they do. He didn’t have any reason to do what he did with me other than the character the man has.”

Lindsey, 77, now lives in Charleston, S.C., with his daughter, Michelle, following the death of his wife, Linda, in 2017 after 52 years of marriage. His three years at Tech were a long time ago, but still cherished.

“I’ve been blessed to have been around great victories, great teams, all that kind of hoopla stuff,” he said. “And there is not a single season or a single school or place or time that I’ve enjoyed more than the three years I spent at Georgia Tech.”

About the Author

Keep Reading

The Latest

Featured