In July and August 1996, the world sent its finest athletes to Atlanta. Some athletes came as familiar names from familiar nations. Others had toiled in obscurity. Each came proudly to Atlanta, and Atlanta received them in the same manner. To commemorate the 20th anniversary of those Summer Games, the AJC offers 20 memorable athletes and performances.

The seventh in the series: Gail Devers wins gold in the 100 meters.

Gail Devers ran her last race some nine years ago at the overripe age (in track years) of 40. She went out a winner, indoors in the 60-meter hurdles, at the Millrose Games.

Long retired, however, does not mean untitled. Here she is today Gwinnett County’s, if not the world’s, fastest school volunteer mom.

Anybody out there want to challenge that? Maybe a quick sprint down the bus drop-off lane, winner gets a construction-paper medal?

Winner of Olympic gold in the 100 meters in Barcelona in 1992 and Atlanta in 1996, Devers has settled into the untimed roles of track ambassador and mother.

Her own job description is simple enough. “I am mommy when I’m not travelling (as a speaker or doing work for U.S. Track and Field),” she said. “I am volunteering at the schools, helping doing fundraisers and stuff like that. I get a joy out of that.”

There are a couple of ways to ramp up her already high-rpm speech to turn-four-at-Daytona levels.

Ask her about her daughters — 11-year-old Karsen and 8-year-old Legacy. Karsen being the creative one, who just the other day designed and sewed a skirt, box pleats and all. Legacy being the friend to all who when inevitably asked what legacy a girl by her name hopes to create answers, “To be myself.”

Or ask Devers about the new wave of runners the U.S. will dispatch to Rio de Janeiro for the Summer Games. She can’t help but become emotionally involved in the race, even if she is no longer running it. Devers won’t be in Brazil, but, as a U.S. Olympic Committee envoy, she will be in Houston, where the Americans will stage before heading to South America. There, she’ll dispense all the sage advice of a three-time Olympic and five-time World Championship gold medalist, the last American woman to claim an Olympic 100-meter gold and the unofficial title of world’s fastest woman.

A funny thing happened once Devers got out of the blocks and onto the couch. “I really did not get nervous when I competed, but I get so nervous when these kids are competing,” she said. “I’ve become a great big fan. I’m up. I’m jumping. I’m yelling, ‘Go, go, go.’”

And, what, exactly might be the dominant bit of instruction that she’ll offer the next fast-twitch-muscle generation?

There’s more than one piece, actually, she said:

“Keep doing what got them there. And what got them there was hard work and determination. Don’t let this next phase be any different.

“You are representing yourself and your country. Set a goal for yourself that you put in your mind, a realistic goal. And write it down and put it on your hotel wall, so you see it every day, when you brush your teeth.

“Now that you made it to the Olympic team don’t be satisfied just saying I’m an Olympian. Go out there and give it your best. Going out there and giving it your best and being successful does not mean you’re going to win every race. Being successful means giving your 110 percent effort. Even though people say you can’t give more than 100 percent — yeah, you can. That’s the little oomph that takes you there. You were born a champion. Now it’s just time to let that shine.”

Another nugget she might want to pass along: Give Rio, for all the dire reports coming out of there in advance of these Games, a chance.

After all, her first notions of Atlanta were negative. So spooked was she by predictions of traffic snarls in 1996 that she stayed in a hotel just across the street from the Olympic Stadium. Devers literally walked to work in those Games. And yet within four years after that, a native of faraway Seattle was choosing to move to metro Atlanta to raise a family (in Buford, these days).

By the Atlanta Games, Devers’ place in track already was well established. She was one of the bright stories of the 1992 Barcelona Olympics, having overcome Graves’ disease, an autoimmune condition that is just about as grievous as the name implies, to win the 100 meters.

Her goals in ’96 were both grand and redemptive: Become the first woman since Wyomia Tyus (1964 & ’68) to defend the Olympic 100-meter title and come back from her ’92 performance in the 100-meter hurdles when she tumbled over the final hurdle.

She went 1-for-2.

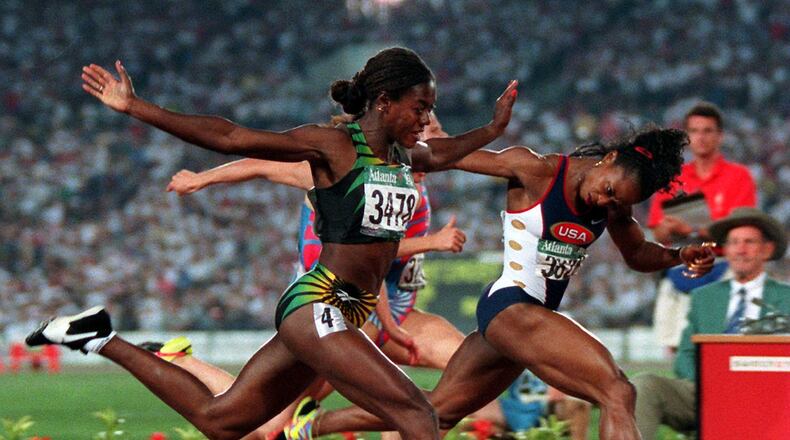

Once more, she won the 100. Once more, as in Barcelona, it was a photo finish, in which she won by the slimmest of margins, out-leaning Jamaica’s Merlene Ottey to win by 1/100th of a second.

Famed for her extravagantly long nails, Devers would have been excused had she chewed them to the quick while awaiting the camera’s verdict in both 1992 and ’96.

Recalled Devers: “I remember standing there at the finish (in Atlanta), and (bronze medalist Gwen Torrence) came up to me and said, ‘I think you got it, you got it.’ In my head I’m thinking uh-uh, I am not going to listen to you. I want to listen to you, but you are not the announcer.

“You want them to say anybody’s name just to take the tension off the moment. I want to breathe again, can you say something? It seemed to take forrrr-ever.”

And once more she was denied a dashing double, this time at least staying upright, avoiding the skinned knee, but nonetheless finishing fourth in the 100-meter hurdles.

It was the metaphorical hurdle that Devers cleared without fail. A couple of months before the ’96 Games, she was coming back from calf and hamstring problems that had scotched her indoor season. Running in a Grand Prix event on the Atlanta track, she finished sixth, casting doubt on whether she’d even make the U.S. team, let alone win gold.

“Don’t count me out,” she remembered telling one questioner at the time. After all, hadn’t she already defied the treatment for the Graves’ disease that had so damaged her feet that amputation had been discussed? This was nothing.

No wonder that now, as she gets her daughters ready for bed and they engage in “ask Mommy whatever you want” time, there is one response that Devers finds herself so often employing.

“I’m always telling them don’t let anyone ever count you out,” she said. “It’s called belief. Belief in yourself, regardless of what other people believe about you. It’s what you believe in yourself and what you want to work for.”

About the Author

Keep Reading

The Latest

Featured