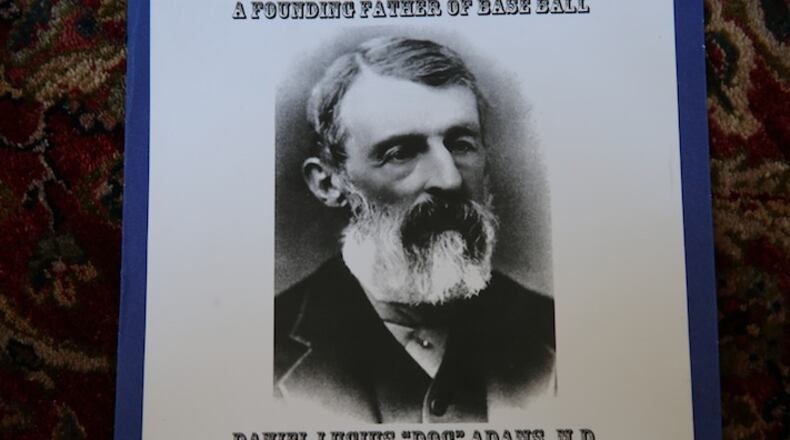

Before Derek Jeter made his mark as New York’s most illustrious shortstop, there was another player, popularly known as Doc Adams, who in the mid-1800s invented the position while playing for a different local powerhouse, the Knickerbocker Base Ball Club.

Daniel Lucius Adams (that was his formal name) was a pioneering figure in the sport’s early years, when mitts were unheard-of, balls were spongy, pitches were thrown underhand and the game’s rules were far from standardized — including the number of players allowed on the field, how many innings constituted a game and the dimensions of the diamond.

Adams is credited with establishing the modern diamond by setting the distance between bases at 90 feet, the current standard.

He was also a standout player at the position he created to relay throws from the outfielders to the infield.

Despite his accomplishments, Adams’ descendants lament that he has been largely overlooked by history. He has never even made the ballot for election to the National Baseball Hall of Fame in Cooperstown, N.Y.

His relatives say his induction is long overdue and are campaigning to get him on the ballot next month, engaging a selection process for “pre-integration candidates” that occurs only every three years. It is the hall’s designation for figures whose most significant contributions to baseball came before 1947, when Jackie Robinson became the first African-American to play in the major leagues.

These candidates are considered separately from more modern figures, whose selection to the Hall of Fame is voted on every year. Adams’ relatives had no luck when they tried petitioning the Hall of Fame to elect him in 2012.

They hope that the current baseball fever in New York — both the Mets and the Yankees made the playoffs — will amplify their efforts to get a New York figure elected.

Marjorie Adams, 67, a great-granddaughter of Doc Adams, has led the family’s effort; she serendipitously met a baseball historian in the 1990s and discovered she was descended from baseball royalty.

The historian told her that the Knickerbockers were the most important baseball pioneers during a seminal period in New York before 1850 and that Adams, in urging members to show up for practices and games, helped keep the Knickerbockers intact during the late 1840s, when sagging enthusiasm could have caused the club to fold.

“He said, ‘You know, your great-grandfather saved baseball,’ ” Marjorie Adams recalled. “The game could just as easily have died and faded away.”

This stuck with Adams, and in 2011, after seeing a brief mention of a local baseball historical organization, she attended a lecture and heard mention of Doc Adams’ importance to the game.

“I nearly fell off my chair,” said Adams, who then spent an obsessive few years researching her relative. “I realized that it was true: Doc did save the game.”

Since then, she has thrown herself into the world of old-time baseball, traveling to numerous conferences and vintage baseball festivals and pestering Hall of Fame officials, who smile when they hear her name.

“I can be a terrible nag,” she said, “but I’m doing this for Doc.”

Marjorie Adams, a retired furniture-store designer who lives outside New London, Connecticut, said her lack of interest in baseball made her an anomaly in the Adams family, which had known of Doc Adams but not of the full extent of his contributions to the game.

Her sister, Nancy Adams Downey, of Manhattan, recalled that relatives referred to him as “Daniel, the baseball guy.”

Adams Downey remembers growing up as a tomboy and playing pickup baseball games with local boys and telling them, “My great-grandfather invented shortstop.”

Today, Marjorie Adams can talk for hours about the early game, dispensing tidbits such as the fact that this year is the 170th anniversary of the formation of the Knickerbockers.

For Doc Adams’ sake, she joined the Society for American Baseball Research and delivered a spirited presentation recounting his achievements. He was later named by the society as the “19th-Century Overlooked Baseball Legend” for 2014.

Her expertise draws respect from top historians, including John Thorn, the official historian for Major League Baseball.

Thorn, who wrote about Adams in his 2011 book “Baseball in the Garden of Eden,” said he “has been sorely neglected by history.” He called Adams “the most significant figure in the early history of baseball.”

Among the material Marjorie Adams has presented to the hall are family letters dating from the early 1830s mentioning the “bats and balls” a teenage Adams used growing up, as well as the brass buttons from his Knickerbockers uniform, which the family believes may be some of the oldest such remnants extant.

Adams had attended Yale and Harvard before setting up a medical practice in Manhattan around 1840. During his career, he worked at city dispensaries treating poor New Yorkers, often during cholera outbreaks.

He began playing baseball with other medical professionals in 1840, for exercise, and joined the Knickerbockers in 1845. The team played in Madison Square Park, then in Murray Hill, and later at the Elysian Fields in Hoboken, New Jersey, which some historians have credited as being the site of the first organized baseball game, on June 19, 1846.

Adams served several terms as the club’s president, helping run early conventions and sitting on rules committees to help standardize play. He put into effect the rules requiring nine-member teams and nine-inning games, and advocated the “fly rule,” which made catching a fly ball a putout at a time when a ball caught on one bounce still constituted one.

He also officiated as an umpire and is credited by some historians as being the first to declare a batter out on a called third strike, in 1858, Thorn said.

On a recent weekday, Marjorie Adams produced a copy of a proclamation that Knickerbockers members presented to Adams in 1862. It named him “the Nestor of Ball Players,” a reference to the wise king in Greek mythology.

About the Author

Keep Reading

The Latest

Featured