Why Tech lineman Eason Fromayan wants to be on a NASCAR pit crew

Eason Fromayan did not find football until high school. But it turned into his route to a college scholarship and, as of this past Saturday, a Georgia Tech degree in business administration.

Diploma in hand and a solid season behind him, Fromayan is now ready to engage the passion he has nurtured for much longer – NASCAR. Fromayan has a year of eligibility remaining and a clear opportunity to hold his spot in the Yellow Jackets’ offensive tackle rotation, but he is leaving school and football to try for a career as a pit-crew member.

“I guess it’s unusual to cut a career like this, but I’m graduating and everything,” he said. “We accomplished a lot here.”

Fromayan, from Milton High, will play his final game Dec. 31 against Kentucky at the TaxSlayer Bowl in Jacksonville, Fla. Then he hopes to trade the Ramblin’ Wreck for rides with a bit more juice.

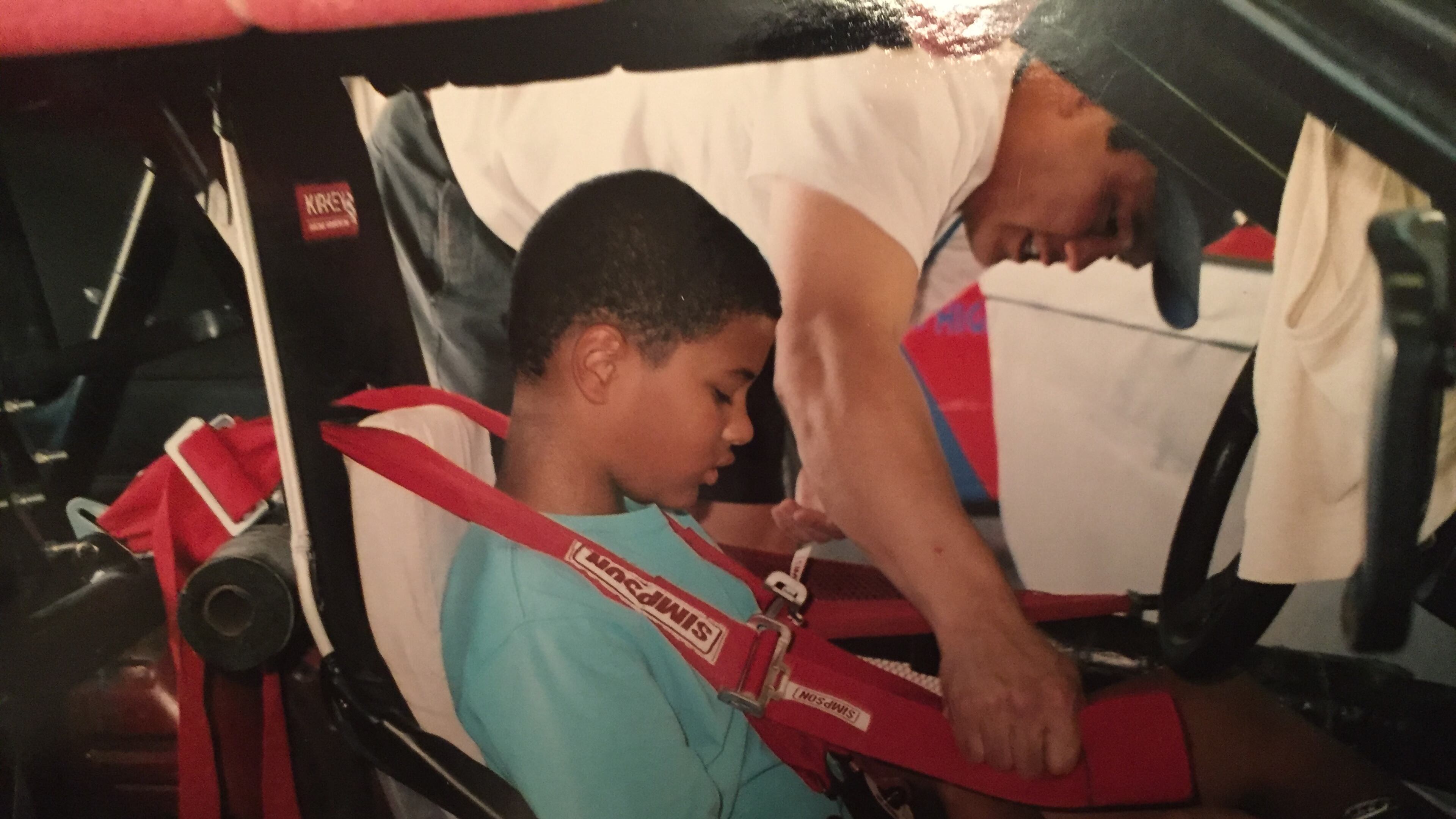

Fromayan has been a NASCAR fan since childhood and loyally followed driver Jeff Gordon. His family has several pictures of him dressed up in Gordon’s Rainbow Warrior fire suit. Fromayan estimates that he’s been to perhaps 40 or 50 races at tracks from Texas to Florida to Virginia.

When teammates chilled out on Sundays watching the NFL, Fromayan was glued to Sprint Cup races.

“He knows everything,” offensive tackle Trey Klock said. “I don’t know many of the drivers at all, but if I have questions, he loves talking about it. He’ll write papers about it in any way possible in some of his classes. He’s really into it.”

Last year, Fromayan took Klock to Talladega Superspeedway in Alabama for a race.

“He was just focused in,” Klock said. “Some of the questions I would ask, he just could not believe I didn’t know.”

This past summer, he interned at Atlanta Motorsports Park in Dawsonville, helping monitor races on the serpentine track.

Last year at a race at Atlanta Motor Speedway, Fromayan met the man he calls the poster child for the football-to-NASCAR transition, former Wake Forest linebacker and Lakeside High grad Dion Williams. Hanging around the garages, he said his Orange Bowl ring caught the attention of Williams, a front-tire carrier for Sprint Cup driver Chase Elliott.

The two talked, and Fromayan said Williams planted the idea with him that he could pursue NASCAR as a career.

Thanks in part to Williams, the opportunity to jump from football to NASCAR has opened up in recent years. Pit crews were long made up of mechanics, people not necessarily possessing the size and strength to deftly carry an 80-pound fuel can or a 20-pound hydraulic jack. With millions of dollars at stake in races often decided by a quarter second or less, race teams have streamlined pit stops by recruiting and hiring football players and other athletes whose careers have reached their limits.

It's a natural move in a lot of ways — football players typically have size, strength and agility and are trained to move in concert with teammates, each with a specific job. In a story published last month, Williams estimated 80 percent of pit-crew members are former Division I football players.

“You go up on pit road, half the guys are bigger than I am,” said Fromayan, who is 6-foot-4 and 285 pounds.

To pursue his dream, Fromayan will likely attend a school or camp where he can learn the skills he’ll need to be a part of a pit crew – Fromayan figures he’d work the jack or the fuel can – and then get tested by race teams in combine-type events. He expects he’ll have to start in a lower-level racing series before working his way up to Sprint Cup. Quarterbacks and B-backs coach Bryan Cook and strength and conditioning coach John Sisk have helped with their connections into the world of pit-crew coaching.

Fromayan leaves Tech and football on a high note. The Jackets finished the regular season 8-4, including road wins over Virginia Tech and Georgia. Fromayan started nine games and earned significantly more playing time than he did in his first two seasons at Tech.

“He played much better than he did the year before,” coach Paul Johnson said.

Beyond a pit-crew job, Fromayan has another dream in his pocket. He wants to earn enough money to compete in the Rolex 24 at Daytona, a 24-hour endurance race held at the same track that hosts the Daytona 500.

“It’d be a heck of a story,” he said.