Editor's note: At a time when sports are shut down, including the canceled Final Four in Atlanta and many other postponed events, we take a look (in no particular order) at some of the bizarre moments from Georgia sports history.

The memories – and agony – are not difficult for Bobby Cremins to summon. It was 27 years ago, March 1993. The coach who had built Georgia Tech from an ACC doormat into a national basketball powerhouse had accepted the job at South Carolina, his alma mater.

But not long after arriving in Columbia, S.C., Cremins was shaken up.

“After 24 hours, I knew it was wrong,” Cremins said. “Everything about it was wrong and my body turned on me, and I was in trouble. I was in trouble. I was really in trouble.”

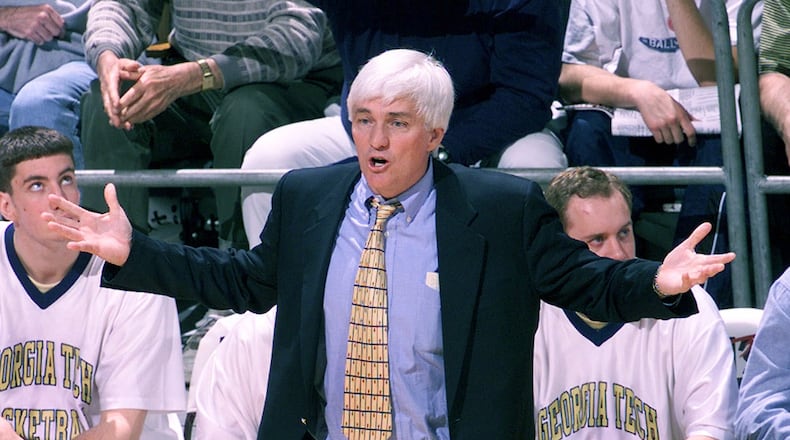

Cremins’ 19-season tenure holds fast as the unquestioned zenith of Tech’s basketball history. The first of the Yellow Jackets’ two Final Four trips, the team’s only three ACC tournament championships and 12 first-round selections are but three data points of the Cremins era. The winning aside, his affable manner, the floppy silver hair, the oft-imitated Bronx accent and the sideline gyrations all captured the hearts of Tech fans.

Among the trove of triumphs, upsets and quips, too, is Cremins’ three-day exodus in which he left Tech for South Carolina and then, overwhelmed with second thoughts and regret, returned to Atlanta.

“It was a mess,” Cremins said in an interview last week with the AJC. “It was the worst time of my life.”

On the face of it, in March 1993, there was little reason for Cremins to leave Tech for South Carolina. The Jackets had just won the ACC championship with four future NBA players (Travis Best, Malcolm Mackey, Drew Barry and Ivano Newbill), with all but Mackey returning. Tech had just made its ninth consecutive NCAA tournament appearance, although the Jackets were upset as a No. 4 seed in the first round by Southern.

South Carolina, two years into its membership in the SEC, had made one NCAA tournament from 1975 through that spring. But then-athletic director Mike McGee took aim at Cremins, a favorite son and connection to the Gamecocks’ greatest basketball days as a point guard for legendary coach Frank McGuire.

But below the surface, Cremins was feeling stressed and exhausted by the job at Tech. Then 45, he said he was going through a mid-life crisis. South Carolina offered a new challenge at a place he held dear.

In the recollection of Kerry Tharp, then an associate AD at South Carolina and sports information director, the late McGee was not easy to resist.

“And so Mike dug his heels in, and he wasn’t going to take no for an answer,” said Tharp, now president of Darlington Raceway.

‘I’m going to do it’

Cremins’ deliberation began in earnest after Tech’s NCAA tournament defeat. According to AJC reports at the time, he told McGee on consecutive days (March 22-23, a Monday and Tuesday) that he couldn’t take the job but wanted to sleep on it.

On that Wednesday, not having heard from Cremins, McGee sent out a news release to the Associated Press that Cremins wasn’t coming. (It was a different time, both in the relative transparency of the coaching search, and also because McGee sent word by fax.) But in Atlanta, Cremins was still trying to decide.

Finally, “I said, ‘What the hell, I’m going to do it,’” Cremins said. “And boom.”

Later the same day, Cremins was introduced at a news conference as the Gamecocks’ new coach.

South Carolina was ecstatic. Tharp recalled him and a colleague going to the NCAA regional held at the Charlotte Coliseum wearing buttons that read “We got Bobby.”

But not long after the news conference, Cremins felt so much distress that he couldn’t sleep. Ever loyal, Cremins felt he had betrayed Tech and his players, to whom he had promised he would stay for the length of their careers.

“I felt like everything I stood for, I went against,” he said. “There was no reason to leave Georgia Tech.”

Tharp remembered visiting Cremins at the basketball office and noticing his weariness.

“He basically, at that time, just told me, ‘You know, I’m not sure if this was the right move,’” Tharp said. “He said, ‘You know, the program’s not in great shape.’ I said, ‘Well, that’s why you’re here, because the program’s not in great shape,’ but you could tell he was really struggling.”

A call at 2 a.m.

At Tech, then-AD Homer Rice readied his coaching search. In an interview last week, Rice recalled that he never got to the point of making calls, but that his first candidate probably was Roy Williams, who was in the midst of taking the Jayhawks to the Final Four in his fifth season. According to an AJC report at the time, a representative of Williams reached out to Tech to express interest.

Rice had a connection to Williams. Rice was AD at North Carolina during coach Dean Smith’s tenure. Williams was a student at UNC during Rice’s tenure, and later served on Smith’s staff.

Given Williams’ Hall of Fame career, it’s a most tantalizing “What if?” conversation. But, given that Williams turned down North Carolina in 2000 out of loyalty to his players at Kansas before accepting the call home three years later, not to mention that coaching at Tech would have meant competing against Smith and the Tar Heels, it’s questionable how much success Rice would have had in a pursuit of Williams.

At 2 a.m. that Friday in Columbia, less than 48 hours after accepting the job, Cremins called Rice, telling him he had made a mistake and wanted to come back. Rice told him to call back later in the morning.

“I said, ‘Did you sign anything?’” Rice said. “He says no. I say, ‘Well, get out of there.’”

Though Cremins had taken the South Carolina job over Tech’s offer of a 10-year contract with the additional assurance that he could stay there long enough (after coaching) for his pension to kick in, Rice had no problems welcoming him back. After meeting again with McGee later that morning, Cremins returned to Atlanta that night, driven by his wife, Carolyn.

“That was (brutal),” Cremins said. “I almost made her turn around (and go back to Columbia) once. I said, ‘What am I doing?’ I was a lost soul.”

On South Carolina’s campus, he was hung in effigy.

Recovery in Florida

Devoid of energy and full of embarrassment, Cremins escaped to Florida for rest and to visit with a psychiatrist.

“My shrink said that I had an affair with my alma mater,” Cremins said.

Cremins was relieved when South Carolina followed up by hiring Eddie Fogler from Vanderbilt, then the national coach of the year. In Atlanta, the hate mail from South Carolina gathered.

“The majority of it was nasty, but I agreed with them,” Cremins said.

Tharp got a letter of his own shortly after, from Cremins. The coach thanked him for his work on his behalf, explained his decision and said he hoped that he hadn’t hurt Tharp.

“It was, I thought, a class move on his part,” Tharp said. “I’ll never forget that.”

In years to come, Cremins returned to Columbia for funerals of close friends, including McGuire, his coach and mentor. He described those visits as “a little tense.”

But the passage of time enabled Gamecocks fans to embrace Cremins again. Cremins, who lives in the state in Hilton Head, is an occasional visitor to Gamecocks games. In 2017, the school named him its SEC legend as part of the league’s annual celebration of its basketball greats.

Cremins’ humility undoubtedly eased the tension.

“People in Columbia, they’ve been great,” Cremins said. “Nobody bothers me anymore.”

The episode does coincide with a pivot in Tech’s fortunes in Cremins’ tenure. Through that March, he had led Tech to nine consecutive NCAA berths, an almost unfathomable achievement in light of the Jackets’ current 10-year tournament drought.

After the South Carolina episode, however, the Jackets made the tournament once in Cremins’ final seven seasons, when one-and-done point guard Stephon Marbury led Tech to the ACC’s regular-season title and the Sweet 16. In February 2000, with Tech headed to its third losing season in four years, Cremins resigned, graciously absolving then-AD Dave Braine of the duty of firing a beloved icon.

As willing as he was to unflinchingly cast himself in a poor light in the South Carolina debacle, Cremins asserted that his temporary departure was not to blame for the downturn.

“People say it hurt me, but, no, I don’t,” Cremins said. “We got to the Sweet 16, and then kids started to turn pro, and I lacked a little foresight. But I think it’ll always be a hurdle in my life, but I think I got over it, I really do.”

The rest of his career

Cremins’ final job, at the College of Charleston (2006-12), could make that case. He won 20 games four times in six seasons, winning the Southern Conference regular-season title once. Citing physical exhaustion, he took a leave of absence in January 2012 and retired at season’s end.

The South Carolina dalliance did come with an epilogue. In 2001, a year after Cremins had resigned at Tech, the South Carolina job came open again when Fogler resigned. His conscience clear, Cremins was interested. McGee came to visit Cremins in Hilton Head. The university’s board was not quite as interested.

“They said, ‘Go to hell,’” Cremins said, laughing. “Which, I don’t blame them.”

It remains a most peculiar episode of Tech and Atlanta sports history.

“That was a very interesting time,” Rice said. “I like to say I hired Bobby twice.”

About the Author

Keep Reading

The Latest

Featured