The bizarre tale of Georgia’s Herschel Walker turning pro

Editor’s note: At a time when sports are shut down, including the canceled Final Four in Atlanta and many other postponed events, we take a look (in no particular order) at some of the bizarre moments from Georgia sports history.

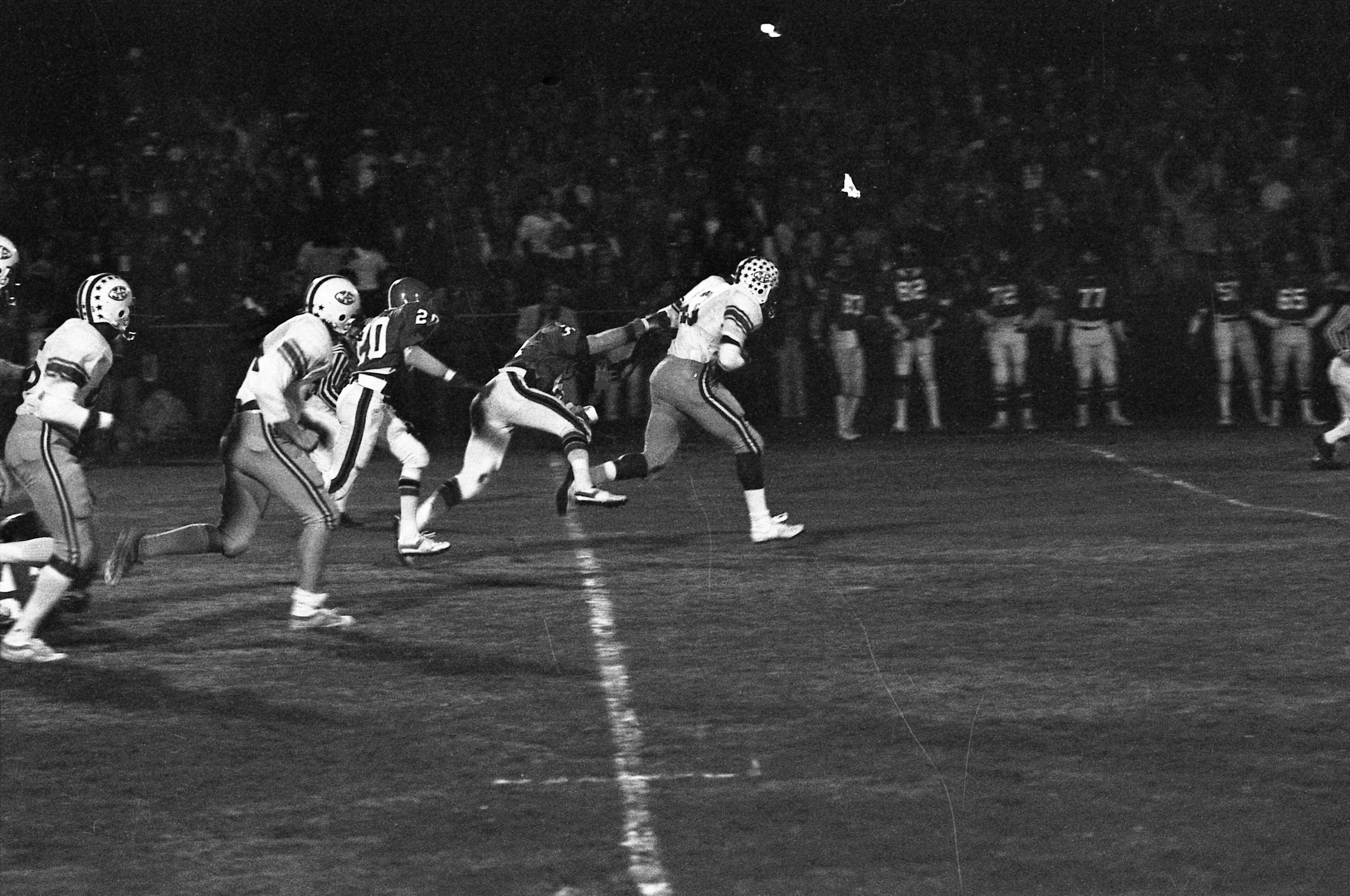

Nowadays, nobody bats an eyelid about a college junior turning professional in football, especially a Heisman Trophy winner considered perhaps the greatest running back in the history of the game. But when Herschel Walker turned pro in February 1983, it was like an earthquake hit Athens, and the tremors were felt from California to New York.

What qualifies the whole affair as a bizarre moment in Georgia sports is how that historical event is remembered today. Or mis-remembered.

The stories are different, depending on whom one asks about it.

- Walker contends a coin flip in his Athens apartment determined his fate.

- Vince Dooley insists his star running back was duped after a signed contract was torn up and flushed down a toilet.

- Still others say Walker and his family were shopping around, looking for the best deal they could get and finally accepting what was at the time the most lucrative professional football contract ever negotiated.

The truth is, it was a little of all those things. Everybody remembers the moment from their own personal perspective. It was, after all, a precedent-setting affair, for the United States Football League, for college football players and certainly for the Georgia Bulldogs.

At the heart of it, though, was a life-changing moment for Walker. The deal that finally got done with the New Jersey Generals set up him and his family for life and fostered professional relationships that he still enjoys today.

“Who’d think somebody like me from Wrightsville, Ga., would have the opportunity to do some of the things I’ve been able to do?” Walker said in a telephone interview from his home in Dallas. “It had nothing to do with money, even though it was going to be the highest-paid contract in pro football at the time. It was just about whether it was the right thing do, about where was I going to continue to play.”

It’s hard to get past the money, though. According to author Jeff Pearlman in his book, “Football for a Buck: The Crazy Rise and Crazier Demise of the USFL,” this was the final accounting on Walker’s deal with New Jersey Generals owner J. Walter Duncan: $2 million up front, $1 million a year for 1983 and ’84, $1.25 million for 1985, a $750,000 loan for investing and a 25% stake in one of Duncan’s oil wells.

Walker verified those numbers in general, but thought it might’ve been “a tad more.” Nevertheless, despite the great riches, it was a decision over which Walker truly struggled.

The hardest thing for Walker was thinking about how his decision affected his teammates. That’s why he waffled so. And that’s what has created so much confusion about what happened during and around the date of Feb. 17, 1983. That's when Duncan and his associates met with Walker, his family and his representation at his Athens apartment.

Dooley was summoned back home from out of town to deal with the fast-developing situation. He said he met with Walker the morning after Walker had signed a contract under an agreement with Duncan to “sleep on it.” Walker was assured that the contract would be torn up and thrown away “like it’d never happened” if he changed his mind about accepting the deal.

In their meeting the next day, Dooley told Walker it’d be a “terrible mistake” for him to take the deal. Dooley did indeed change Walker’s mind, and Walker, in turn, informed Duncan of that.

“(Duncan) was a very honorable man, and he did what he said,” Dooley said. “He tore it up and flushed it down the commode.”

The next day, Georgia held a news conference to announce that Walker had decided to remain at UGA and play his senior season for the Bulldogs, who for the fourth consecutive year were expected to be in the national championship hunt.

“It was big news,” Dooley said. “Everybody was happy and Herschel was happy and I was happy.”

But not long after that, news broke – from the Boston Globe, of all places – that Walker had signed a professional contract. Since he had done so, he was deemed by the NCAA ineligible to play college football anymore.

“Somebody made a copy of the contract,” Dooley recalled. “So that was that. But I really don’t think he wanted to go.”

Walker doesn’t deny that. The son of a Johnson County tenant farmer, Walker knew all the things he was being offered would be life-changing for his entire family. But that was nothing new to him.

It was his teammates and the on-field battles that they waged to mattered to him most.

“I started second-guessing myself, even though we had already decided that I was going,” Walker said. “I love the University of Georgia, and I started thinking about all my teammates I came in there with. I started thinking about Scott Williams and Darryl Jones and Terry Hoage and Clarence Kay. That’s the class that I came in with, which was an impressive class. Going to college, that becomes your family, and now I was leaving my family and going to a whole new situation. It had nothing to do with money.”

Ever since his freshman year at Georgia, when he led the Bulldogs to the 1980 national championship, Walker had been receiving all kinds of behind-the-scenes and under-the-table overtures. The Canadian Football League came after him after his freshman season. And all sorts of characters, shady and upstanding and somewhere in between, had inundated the Walker family with lucrative proposals of every ilk.

That’s why they had enlisted the services of Jack Manton to represent them. They needed somebody to make sense of all these offers coming at them.

Even the NFL, which at that time was not permitted to draft or sign underclassmen, was reportedly working behind-the-scenes to orchestrate a deal with the Walkers that might discourage them from doing business with the USFL.

That was Dooley’s pitch in all this, too. Just wait. It will all be there for you at the end of college, and with a reputable league in the NFL.

But that didn’t take into account the biggest concern inside the Walker camp. What about an injury? What if he got hurt his senior season and couldn’t take advantage of all these overtures coming his way?

That’s what the people closest to Walker, those who were impartial and witnessed it objectively, thought about it.

“I just thought he had done all he could do in college football and it was time to move on,” said Buck Belue, who quarterbacked the 1980 team and also played in the USFL. “He’d won a national championship, a Heisman Trophy, broke rushing records. And let’s face it, his family was poor. They needed the money.”

Frank Ros captained the 1980 team and remains one of Walker’s closest friends. He was a graduate assistant on Dooley’s staff and counseled Walker when all this was going down.

“It all kind of happened fast and Herschel was confused about what he should do,” Ros said. “I was a kind of mentor for Herschel back then, his big brother when he came to Georgia, and we talked about it. I said, ‘Why did you come to college? To get a degree. What do you get a degree for? To get a good job. Why do you want a good job? So, I can take care of the family. So, I told him, you just hop-scotched all that with the kind of contract you’re going to get.’”

And that’s the happy ending to this story. After a three-year career at Georgia that ended with 5,259 yards rushing and 53 touchdowns, Walker went on not only to a great professional career. It included not only a historic three-year stint with the USFL, but also an underappreciated 12-year NFL career with the Dallas Cowboys, Minnesota Vikings, Philadelphia Eagles and New York Giants. He accounted for more than 25,000 total yards and 177 touchdowns as a pro.

There’s no telling how much money Walker earned as a pro, on and off the field, but he’s still earning money today as a result of it. The holdings of Herschel Walker Enterprises include chicken-based food distribution company called Renaissance Man that employees more than 60,000 people and numerous other ventures, many of which were spun out of that initial deal that took him away from the University of Georgia.

Rather than sign a standard contract with the USFL, Walker's team negotiated a personal-services contract with Duncan, meaning all his money was guaranteed regardless of whether the league survived, which it ultimately did not.

In 1984, the oil magnate Duncan sold the Generals to a New York real estate mogul by the name of Donald Trump. Today, that man is best known as President of the United States. He and Walker remain "very, very close," Walker said.

In 2018, Trump appointed Walker as co-chair of the President’s Council on Sports, Fitness and Nutrition. It’s one of several boards for national causes on which Walker has served, including those supporting the U.S. military and mental health awareness.

"In 1985, there was an article somebody did and in I said, 'I think this guy can be president of the United States,'" Walker said of Trump. "I had no clue 30-something years later he would become President of the United States. But the reason I said that was how much he loves the United States of America. Being around him as much as I was while I was in his family, I was able to see that. What's so unique about it is we're still close."

Political ideologies aside, that relationship and others dating back to that fateful day in February 1983 have served Walker well -- including the one with the University of Georgia.

Even though Walker gained so much from his decision to leave UGA, it still pulls at him what might have been had he stayed one more season. No doubt, he’d own a college rushing record that would still stand today. But he was always a team guy.

Walker said he remembers attending the Cotton Bowl in which Georgia defeated No. 2 Texas 10-9 on Jan. 2, 1984, in Dallas. He knows how good that team was, and how awesome they could have been with No. 34 still in the backfield.

“I watched that team that I would’ve been on beat Texas that day and, well, you never know what could’ve happened,” Walker said. “As a team, we had coaches and players who believed in each other and we felt like we could beat anybody. That class I came in with was absolutely incredible. I think (current Georgia) coach (Kirby) Smart is doing an incredible job with his recruiting, but I still don’t think anybody’s had a recruiting year like we had the year I came to Georgia.”

On that, he and Dooley agree. As it was, the Bulldogs’ 13-7 loss to Auburn late that '83 season was Georgia’s only SEC defeat in four years.

“We somehow beat the best defensive team I have ever seen in all my career in Texas and ended up fourth in the nation without Herschel,” Dooley said. “If we had Herschel, we’d have been champions again, I’m sure.”