To Georgia Tech great Lucius Sanford, Pepper Rodgers was a coach for whom he had to learn how to do somersaults and also who helped advance the integration of the Yellow Jackets football team.

To college football hall of famer Randy Rhino, Rodgers was an innovator and a playcalling maestro. To Tech grad and longtime NFL coach Jimmy Robinson, Rodgers was a coach who gave him his first professional break. To Tech athletic director Todd Stansbury, Rodgers was a man who changed his life’s course as a teenager and later became a mentor. To Buck Shamburger, Rodgers was a teammate and later a coach he sent his son to play for.

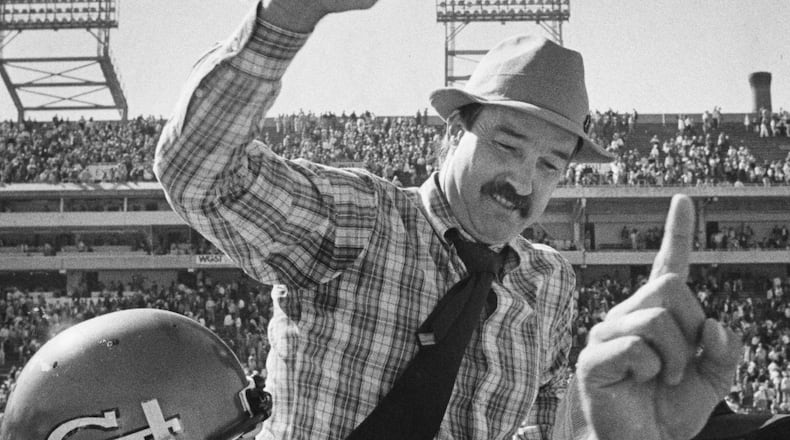

Friday, a day after Rodgers' death at the age of 88, the five recalled a unique man whose imprint on Tech football and its players is irrevocable.

“As I reflect on my journey, so much of it I owe to Pepper,” Stansbury said.

Stansbury was perhaps 13 or 14 when his family traveled from Ontario to Daytona Beach, Fla., for spring vacation. Stansbury’s family happened to share a hotel with visiting Tech football players, and Stansbury was taken by quarterback Scott Zolke, who, among other things, rode a tricycle off a diving board. Zolke invited Stansbury and his family to visit Tech on their way back, which they did, attending a Yellow Jackets practice and meeting Rodgers.

It was Stansbury’s first time on a college campus, not to mention his first visit to a football practice. (Stansbury played hockey and lacrosse.)

“And then to meet the head coach and him to be so engaging, he had a huge impression on me, to the point where I decided right then and there I wanted to come play football at Georgia Tech, even though I’d never played the game before,” Stansbury said. “A guy that took some time with a 13- or 14-year-old kid and basically over the course of that conversation said, ‘Come back and see me in four or five years. You may look like you may end up being one heck of a football player.’ ”

Stansbury had never played football, but took it up in high school and, a few years later, was part of Rodgers’ final recruiting class, signed after his dismissal in December 1979.

While Stansbury never played for Rodgers, they stayed in touch over the years. Stansbury spent two days with him when Rodgers was the coach of the USFL Memphis Showboats and Stansbury was completing his master’s thesis on running a professional sports franchise for his sports administration degree. He later consulted with him on career moves, Stansbury said, and then grew closer once he became AD at Tech in 2016.

“He’s just somebody that’s always been there,” Stansbury said.

Sanford played for Rodgers on his way to an NFL career. Sanford, who is African-American, said that his recruiting class included significantly more black players than previous classes at Tech. He recalled that, the first time they met, he directly asked Rodgers if he would play favorites in regards to race.

“I remember Pepper saying something like, ‘Hey, believe me, I recruit white, black, orange, green, blue,’ ” Sanford said. “’It doesn’t matter the color. If you can play football, if you can play and help me win, I’m going to recruit you.’ ”

Sanford called Rodgers “probably the right guy for the job in terms of that period.” Sanford also laughed as he recalled how, as a freshman, he had to stay after a preseason practice to work on his somersault. Unimaginable as it might be, Rodgers on occasion was known to do somersaults leading his team on the field. Sanford recalls that players sometimes joined in as well, leading to his post-practice tumbling drills.

“Man, I forgot all about that,” Sanford said.

Rhino recalled other, perhaps more meaningful, innovations. Rhino, who was a senior in Rodgers’ first season, said that Rodgers built the team’s first weight room and developed the strength program. Rodgers also had female exercise instructors lead stretching exercises, a new facet of practice.

Rhino also remembered how Rodgers favored wearing a sailor’s hat, sometimes brought celebrities to practice and once took his team to a Friday night movie before a game that he had a small part in, “The Trial of Billy Jack.”

“There was never a dull moment, let’s just say, playing for Pepper,” Rhino said.

Shamburger backed up Rodgers at quarterback on Tech’s 1952 team that finished 12-0 and earned a share of the national championship for coach Bobby Dodd.

“Pepper was a character,” Shamburger said. “He was a favorite of coach Dodd, and maybe not the best athlete at his position, but good enough to be very effective.”

Years later, he sent his son Bucky to play running back for Tech, where he thrived in Rodgers’ wishbone offense.

Robinson was a classmate of Rhino’s, playing only his final season for Rodgers. In 1984, after Robinson’s NFL playing career ended, Rodgers hired him to be an assistant coach on his USFL team, despite the fact that he had no coaching experience.

“That’s not something that happens,” Robinson said. “It definitely doesn’t happen nowadays.”

Robinson remembered, too, how Rodgers was a light touch as a supervisor. Where seven-day work weeks and 12-hour days are the norm in coaching, Robinson said Rodgers once found out that he had worked late the previous day and told him to go home earlier to be with his family.

While Rodgers’ fun-loving reputation was one thing, it didn’t mean he was a pushover. In his lone season playing for Rodgers, when he was part of a communication breakdown for play calls signaled in from the sideline, Robinson remembered Rodgers blistering all involved.

“Pepper was a fun guy to play for, but he was demanding,” Robinson said.

Said Sanford, “Pepper was a character, but he was very serious as a coach. He wanted you to have fun, but he would definitely work your butt off.”

The results spoke to his effectiveness. He had four winning seasons out of six at Tech, after his two predecessors (Bud Carson and Bill Fulcher) had a combined two in seven. He was twice named Southern Independent coach of the year at Tech, adding to twice winning conference coach of the year honors at both Kansas and UCLA.

Running the wishbone, Rodgers “was an absolute genius, kind of like Paul Johnson in the triple option,” Rhino said.

Rodgers’ 34-14 win over Georgia in 1974, his first season, is one of only four Jackets victories in Athens by 20 points.

“He’s a guy that’s intertwined with the history of Georgia Tech in so many ways, both as a player and as a coach,” Stansbury said. “That’s why people say he was definitely a Tech man.”

About the Author

Keep Reading

The Latest

Featured